Report warns of looming global water crisis

Kathmandu, July 10

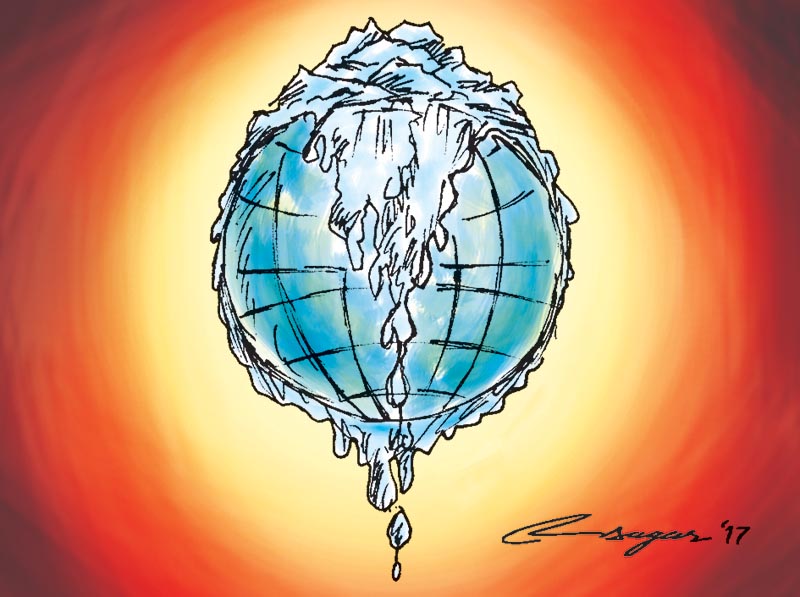

A global water crisis is looming on the horizon. In many places around the world, it is at the doorstep rather than the horizon, exacerbated by a growing global population and accelerated climate change.

The solution may come, at least in part, from paying more attention to forests.

The relationships among forests, water, climate and people are complex, go largely unrecognised and lead to the question: What can people do with, to, and for forests to ensure a sustainable quality and quantity of water necessary to the health and well-being of both?

That question is addressed in a new and comprehensive scientific assessment report released today at the United Nations High-Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development in New York.

The report underscores the importance of embracing the complexity and uncertainty of climate-forest-water-people linkages to prevent irrational decision-making with an unintended consequence.

The publication, entitled ‘Forest and Water on a Changing Planet: Vulnerability, Adaptation and Governance Opportunities. A Global Assessment Report’ was prepared by the Global Forest Expert Panel on Forests and Water, an initiative of the Collaborative Partnership on Forests led by the International Union of Forest Research Organisations.

“Governments and all stakeholders wanting to achieve the SDGs (the Sustainable Development Goals related to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development) need to understand that water is central to attaining almost all of these goals, and forests are inseparably tied to water, said Hiroto Mitsugi, assistant director general, Forestry Department, FAO, and chair of Collaborative Partnership on Forests. “Policy and management responses must, therefore, tackle multiple water-related objectives across the range of SDGs, and take a multiple benefits approach,” he added.

There is, the report says, a clear policy gap in climate-forest-water relations that is waiting to be filled.

Nepal is already hit by water crises and is addressed in the report, Susan Tonassi on behalf of the International Union of Forest Research Organisations shared.

“Aditi Mukherji from International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development and Dipak Gyawali from the Nepal Academy of Science and Technology contributed to the report,” she said.

The new report on the intricate links among forests, water, people and the climate argues that ensuring the continued flow of ‘green water’ — the water moving through trees, plants and soils — is the only way to maintain a healthy global water system.

The report highlights that watershed experts of the Nepal Water Conservation Foundation have already made some counterintuitive findings in the Bagmati watershed regarding the role of traditional recharge ponds, landslides and village spring flow enhancement. Finding landslide control with conventional check-dam building both expensive and ineffective, the Bagmati watershed managers experimented with reviving ponds on the ridge tops, most of which were also buffalo wallowing ponds but had been abandoned and silted up.

They found that for a minimal cost of cleaning up the ponds or excavating new ones, landslides were stabilised.

The post-hoc explanation is that by putting a break on the flow of floodwaters gushing down during heavy rainfall in monsoon, the erosive power of water was significantly reduced.

Similarly, drying of mid-hill springs were related to either earthquake disturbances or social drivers such as outmigration of youth, decline in livestock and the concomitant abandonment of buffalo wallowing ponds that also served as sources of recharge; unregulated use of Poly Vinyl Chloride pipes and electric pumps; shift from dryland crops to water-intensive vegetable farming etc.

Given that rainfall was as stochastic as ever and there was no noticeable decline in precipitation, climate change could not account for the current situation although it is predicted to exacerbate the situation unless the current drivers are first addressed.

In Nepal and China, outmigration and labour shortages in mountain villages are the main cause of land abandonment, the report said.