Wanted: Maximum tailwind of exports

Kathmandu, September 2

The tailwind of merchandise exports in Nepal’s economic growth has sputtered to the most minuscule level in recent history — a precursor that the country may not be able to sustain growth achieved in the last three years and continue facing problems of joblessness and shrinking foreign exchange reserves in the coming years.

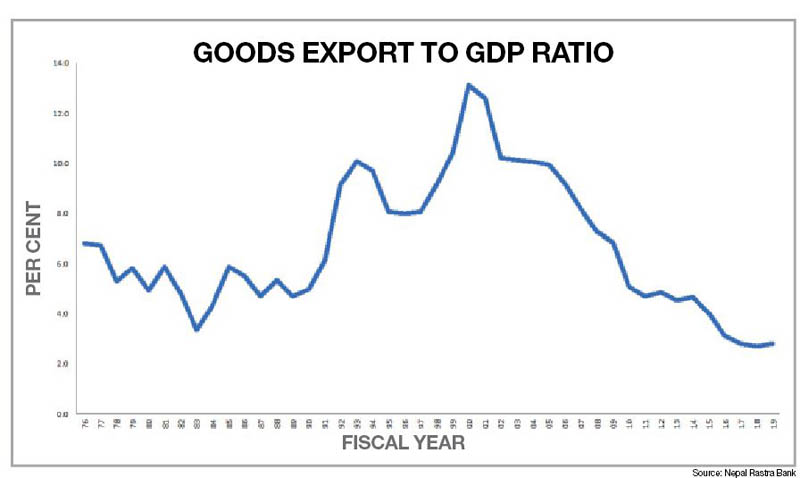

Nepal’s merchandise exports as percentage of gross domestic product stood at 5.4 in Fiscal Year 1975. This roughly means for every Rs 100 of goods and services produced in the country, goods of Rs 5.4 were exported in that year. Fast forward to FY 2019, which ended in mid-July, Nepal’s export-to-GDP ratio slumped to 2.8, the report released yesterday by the central bank showed. This ratio is tad higher than all-time-low export-to-GDP ratio of 2.7 recorded in FY 2018, but almost half of 1975 when the central bank started keeping trade data.

The weight of exports in Nepal’s economy has hit rock bottom at a time when the government has charted out a plan to grow at an average of 9.6 per cent per annum in the next five years. Nepal intends to attain similar growth level till 2030 to become a middle-income country.

But international experience shows that countries cannot achieve rapid economic growth without strong support of exports. Asian economies such as China, Hong Kong, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Singapore, Taiwan and Thailand attained growth rate of seven per cent or more per annum for at least three decades largely on the back of exports. This rapidly pushed up their per capita income.

Nepal has registered growth of above six per cent for three consecutive years. But this growth was largely stimulated by domestic demand triggered by surge in money sent by Nepalis working abroad.

“A growth model powered by domestic consumption is not sustainable because the Nepali market is not big enough to foster near-double-digit growth,” said Posh Raj Pandey, chairman of South Asia Watch on Trade, Economics and Environment. “So, we must rely on external markets to attain high growth for which exports are a must.”

Exports generate foreign income, keeping foreign exchange reserves robust. Exports, especially those of merchandise goods, also help in job creation, enhancing purchasing power and preventing labour flights. What’s more, exports provide exposure to foreign markets and competition, which can play a key role in enhancing productivity and honing production and trading skills of domestic firms, said Pandey. This ultimately results in creation of high-paying, quality jobs.

But here is the harsh reality: Nepal’s exports are 15 times less than what they should be, according to the latest World Bank report. This means Nepal has not been able to tap its export potential.

Nepal’s export-to-GDP ratio hit the peak of 13.1 in FY 2000, largely on the back of surge in sale of readymade garments, woollen carpets and pashmina in overseas markets. But exports of these products gradually fell following abolishment of duty-free quota-free agreement or tough competition from India and China. This prompted manufacturing sector’s contribution to GDP to dip from nine per cent in FY 2001 to 5.6 per cent in FY 2019.

Over the years, Nepal has tried to resurrect exports by providing a rebate of up to five per cent of the value of goods shipped abroad. It has also launched Nepal Trade Integration Strategy, an export promotion blueprint which has identified nine goods that Nepal can sell abroad.

These strategies, to some extent, have raised the volume of merchandise exports, which hit Rs 97.1 billion in FY 2019. But the weight of merchandise exports on the economy has not gone up.

So, till date, Nepal’s biggest export has remained unskilled human resources, who work in Malaysia and the Gulf and send home hundreds of billions of rupees every year. Nepalis employed overseas sent Rs 879.3 billion, equivalent to 25.4 per cent of the GDP, in FY 2019, up 9.7 per cent compared to a year ago.

Remittances have rapidly raised disposable income of Nepalis. But the income hike has also pushed up labour cost, property price and, ultimately, production cost. “This, on the one hand, has made Nepal’s exports expensive and on the other fuelled imports to cater to growing domestic demand,” Hans Timmer, World Bank South Asia chief economist, told THT during his recent visit to Nepal.

This problem, coupled with 25.4 per cent fall in foreign direct investment, pushed Nepal’s balance of payments into a negative of Rs 67.4 billion in FY 2019. This means outflow of money from the economy surpassed inflows by Rs 67.4 billion. This is the first BoP deficit recorded by Nepal in nine years, which prompted foreign exchange reserves to shrink 5.8 per cent to US$9.5 billion in FY 2019.

“Nepal, so far, has been tempted to promote niche exports such as cardamom, ginger and tea. This is welcome, but grossly inadequate to form bedrock of a broader export-oriented strategy aimed at raising export value from millions to billions,” said Swarnim Wagle, former vice-chairman of the National Planning Commission. “We should learn from East Asia where export success was tied with large FDI inflows. We must court a game-changing multinational company or two to begin with, like the big splash entry of Samsung or Intel in Vietnam.”