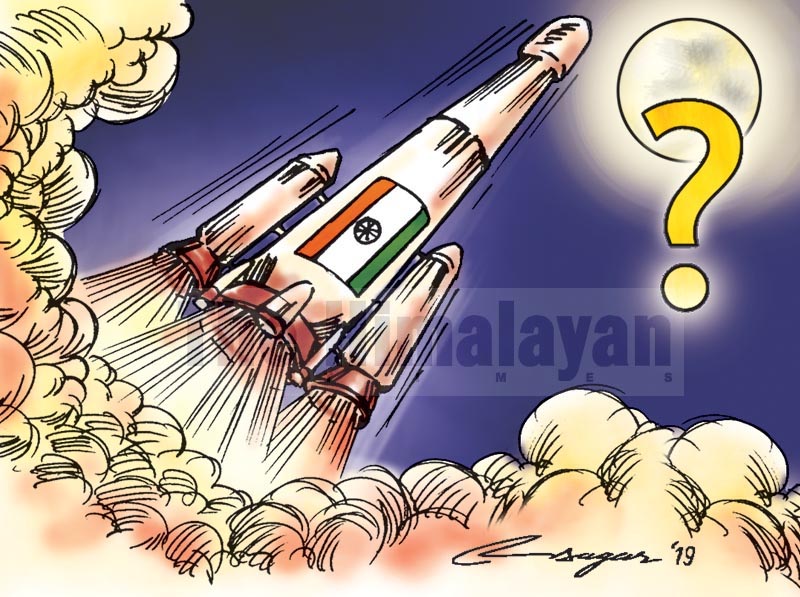

Chandrayaan 2: Will it emulate the Phoenix?

We in Nepal have a lot to learn from India’s space mission, despite its last-minute hitches, in view of a mini satellite launched with the support of Japan’s Kyushu Institute of Technology a few months back

Human beings have been fascinated by the moon since time immemorial amidst infinite number of planets twinkling in the sky. The Nepali people cannot remain exception to this universal reality. No wonder then that the great poet of Nepal, Laxmi Prasad Devkota, wrote ke ho thulo jagatama, pasina bibeka, uddeshya ke linu udi chhunu Chandra eka (What is great in this world is sweat and sense, ambition what to take, fly and touch the moon). His prophecy came true when the Soviet Union sent Sputnik 1 on October 14, 1957 into space. It sent ripples round the globe in general and the United States in particular.

Two days before the great poet died of cancer on September 14, 1959, the Soviet Union again successfully landed a human-made object on the moon.

The lunar wheel came full circle when Neil Armstrong descended on the moon on a ladder after popping out of Apollo 11 on that unforgettable month of July in 1969.

The United States and the Soviet Union ploughed a lonely furrow on space till Australia emerged in the scene on September 29, 1967. Canada quickly followed suit in 1969. Later, several countries took a plunge in the space pool, such as the United Kingdom and China, both in 1970. West Germany took a dip much later in 1974 with India closely following after a year in 1975. India launched its first ever satellite Aryabhatta, christened after its fifth-century scientist. Since then, India has never looked back.

It can be seen glaringly in the initiative taken to send Risat 2 and Chandrayaan both in 2009. Whilst India collaborated with Russia at the beginning of their space adventure, Chandrayaan 1 as well as 2 enjoys the special distinction of being an indigenous innovation.

The space odyssey has never been a bed of roses. Rather it is very thorny with some of them proving even fatal. It has been marked by success as well as failure. When India was seeking to put its satellite in orbit in 1979 with the late former president Abdul Kalam as its director, it lost direction and crazily crashed into the Bay of Bengal instead. Kalam was dazed when Satish Dhawan, then the chief of India Space Research Organisation, took the blame upon himself.

In one of the most interesting memoirs, Kalam describes how Dhawan abstained and requested him to attend the press conference upon the successful launch of the satellite in 1980. It was a staggering example of the boss taking the blame in the case of the abysmal failure and giving credit to the team after the resounding success.

India has thus seen several ups and downs in its space probe. It was observed yet again on September 7, when Chandrayaan 2 was steadily coasting to its destination until 2.1 km away from its 384,000 km journey. Apart from the 1.3 billion Indians, space enthusiasts from round the globe remained glued to their television to catch a fleeting glance of its landing on the moon. India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi, riding on the crest of his second innings as the premier, had already reached the space station in Bangaluru. A state of euphoria was slowly building up, but what followed was an incident that plunged the whole nation in stunned silence. The reason was that the Vikram Lander all of a sudden vanished from the scene and went incommunicado. The scientific community was deeply shaken. It brought tears in some of the scientists. Why should not it be when more than 1,000 scientists had worked on it day and night for the last ten years. The Indian government had spent an astronomical $141 million on this project.

Fortunately, they had their prime minister to console the scientific community in a way that Krishna had preached to Arjun in the Gita. One of the most down to earth verse says that one has the right to perform one’s prescribed action but one is not entitled to the fruit of the action.

In fact, the mission had fulfilled almost 95 per cent of the mission by rubbing shoulders with the moon even though from a distance of a mere 2.1 km. Success can be so close and yet so far. It was reminiscent of Edmund Hillary’s outburst when he failed to reach the top of Mount Everest. He had said how he developed a sense of surety of scaling it the next time as his resolve had increased manifold whilst the height of the mountain remained practically the same.

But it appears that the scientists may not have to wait till the next time. Because the illusive Lander is said to have been located by the orbiter. It appears that the lander is in one piece but slightly inclined instead of being erect due to a rather rough landing. Like the mythical Egyptian bird Phoenix rising from the ashes, the Vikram Lander may begin communicating akin to a person coming back to the senses after being mounted on a funeral pyre.

This space mission, despite its last-minute hitches, certainly united the Indians. They were together in that unfateful midnight, wishing for its success. We in Nepal have a lot to learn from this space campaign in view of a mini satellite launched with the support of Japan’s Kyushu Institute of Technology a few months back.

If the state supports science and technology in the country as has India over the years, Nepal may also dream of sending its spacecraft to the moon one day even if far in the future. This will then be a real tribute to great poet Devkota that the country can ever pay.