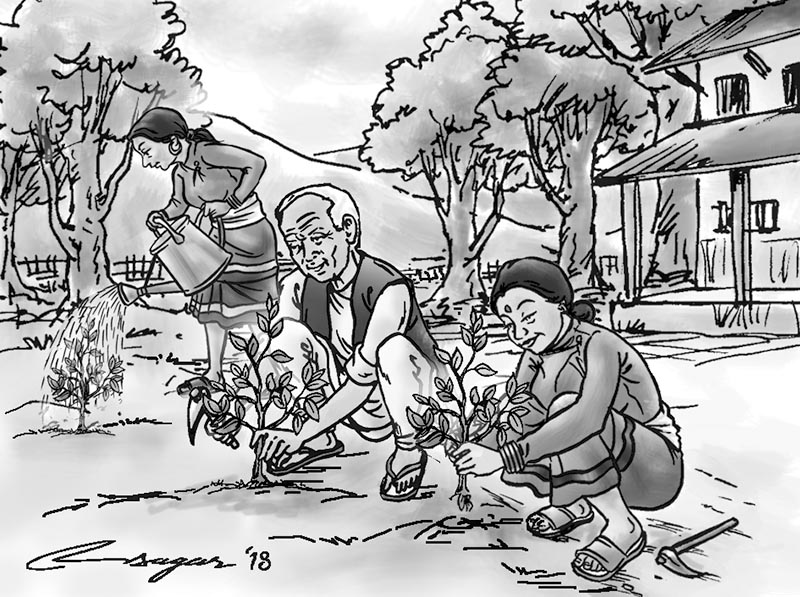

Family forestry: Not out of woods

Family forestry can contribute in biodiversity conservation and generate income and employment opportunities. But family forest farmers are facing various hurdles due to lack of clear policies

The shrinking of forest cover in Nepal due to various reasons has emerged as a major concern. In this context, promotion of family forestry, or private forestry, can hugely contribute in maintaining forest covers. It’s not a new concept though. Family forestry is quite popular in Nepal. Mostly, small landholders are growing trees on their private land. They, however, are facing various hurdles in managing “their” forests in a sustainable way.

Fragmentation of land in Nepal is a very serious issue. Private Forest Development Directives 2012 has made provisions to form groups among private forest owners to establish and run private forestry business. But there is hardly any support programme to run the family forestry business. The Master Plan for the Forestry Sector (1988-2011) had set a target of preparing private forest management plan of 325,000 hectares of private individual land and allocated $811 million for the purpose.

However, there is no update on the expenditure. Nor is there any report available to suggest whether the target has been achieved.

Up until 2017, there were only 3,753 private individuals who had registered 2,902 hectares of their forest as “private forests”. But there is no proper legal framework or provision for legally registering family forests.

Through a 2015 amendment to Forest Regulations 1995, the government has introduced a new provision as per which farmers can directly harvest, sell and transport 23 common trees species which are mostly grown on private land. While this amendment looks good in principle, it is yet to be translated into practice. And there are some contradictions when it comes to certain species.

It is a well-known fact that Sal (Shorea robusta) is being felled and used in government as well as community managed forests in the country. Private

Forest Development Directives of 2011 has included Sal one the species that can be planted and raised in family forest. But restrictions on Sal felling and sale continue to be there. This has put forest landholder in a dilemma—they are not sure whether to plant and protect Sal trees or not.

Recently, this author observed that Sal seedlings were being raised in one of the government nurseries in the Tarai region. Although, the 14th plan has included family forestry in its major programme, some policy makers of the day are still hesitating to translate it into practice through proper laws and regulations.

Hence family forestry today stands at crossroads.

Family forests contribute in conservation of biodiversity and can play a greater role to sequestrate carbon from the atmosphere. Similarly, family forests can generate income and employment opportunities, thereby helping in improving the livelihoods of the people.

Nepal is signatory to the United Nations Convention of Biodiversity Conservation (UNCBD) and UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCC). And the government has already ratified the conventions and formulated a number of policies, strategies and action plans.

But there is no compensation for biodiversity protection and carbon sequestration, which are very genuine concerns of family forest holders. Can Nepal raise the agenda in the forthcoming Conference of Party of United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change?

Moreover, Nepal has regularly assessed its forest resources to know the state of forests in the country. However, the latest report published by the government could not include the statistics of family forests in the country. It is reported that the forest products demand of the country is fulfilled significantly by family forest.

Now time has come to translate the provisions in Private Forest Development Directives 2012 into practice. Formation of groups among family forest owners to establish and run forestry business could be a good starting point. We must promote family forests by ensuring the provision of collateral, insurance and grants from banks.

Similarly, family forest registration process should be eased—for example registration should be made available at ward offices. Small forest holders should not be subjected to lengthy bureaucracy and process while they want to register family forests. Further, all the required permissions related to harvest, use and transportation of the family forests products should be given by ward offices.

Family forests should be considered as agriculture crops. It means there should not be any ban on cutting and transport of any species and products from family forests. While the government should raise seedlings of valuable species like Sal, it should also ensure its free and easy use throughout the country. There should be a provision of providing compensation for contribution in biodiversity conservation and carbon sequestration by family forests through UNCBD and UNFCCC.

The contribution and status of family forests should be reflected in the gross domestic product and forthcoming forest resource assessment report of the government. The government should revise its National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan and come up with policies that are friendly to family forest farmers. The government should make policies and laws as per agreements reached in the past. Voices of family forest farmers must be heard.