For safe abortion practices

In February this year, a 20-year-old unmarried woman was brought to our emergency ward with abdominal pain and rash on her legs and lower abdomen. Her blood pressure was almost unrecordable. It was clear from her appearance that she suffered from disseminated intravascular coagulation, a complication of severe infection. The rashes on her body were, in fact, bleeding underneath her skin.

While examining her it was found that her genital area had many old infected lacerated wounds. The smell of pus was evident despite our N95 masks. An ultrasound test revealed the retained product of conception inside her uterus. These are the tell-tale signs of septic abortion.

This woman belonged to an indigenous population group with poor socio-economic status. She had no formal education. She would be stigmatised in society for getting pregnant. Although safe abortion services are available free of cost throughout the country, she could not access this service. She could not continue with the pregnancy either. So she had undergone an unsafe abortion in her village.

The injuries in her vagina and cervix looked as though her uterus had been penetrated by a shaft to rupture the gestational sac and cause abortion. Such unsterile practices are usually lethal. She soon suffered cardiac arrest. We attempted cardiopulmonary resuscitation but to no avail.

The family members who came along with the patient were hesitant to provide us with the complete history. Even after she was declared dead, and we informed them about the cause of death, none of them were interested in seeking justice for the woman. Instead, they began arguing that this had brought shame to her family. We had no clue about when and who had performed such a dangerous procedure on the patient. We informed the authorities about her death. A post mortem was performed, but that was the end of it, without a formal complaint from the family members.

In countries where abortion is illegal, mortality related to unsafe abortion practices is high. Unsafe abortion results in 4.7-13.2% of maternal deaths worldwide.

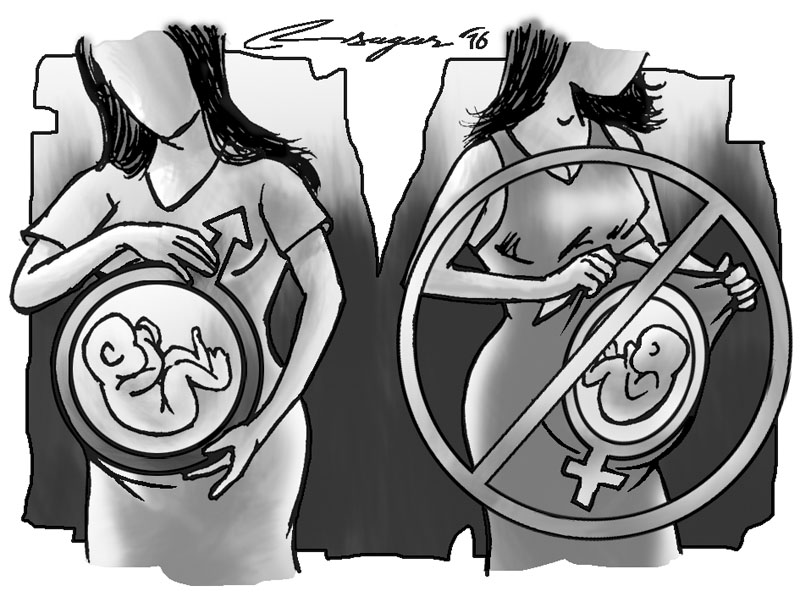

Legal restrictions on abortions usually do not result in fewer abortions, instead, they compel women to opt for life-threatening methods of abortion. It was in light of this that abortion in Nepal was made legal in 2002. The current abortion laws are outlined in the Right to Safe Motherhood and Reproductive Health Act of 2075 BS which has provisions of abortion for up to 28 weeks of pregnancy.

A pregnant woman has the right to safe abortion of a foetus of up to 12 weeks without stating any reasons for it. Abortions beyond 12 weeks and up to 28 weeks are provided to pregnant women as per her consent in cases of rape, birth defects, women with an incurable disease such as HIV conditions and if continuing the pregnancy is a threat to the life of the woman.

The ultimate aim of legalising abortions is to reduce maternal mortality. The years after legalising abortion have seen a significant decrease in maternal mortality in Nepal. Nepal boasts one of the most substantial abortion rights laws in the world. According to the National Demographic and Health Survey of 2011, unsafe abortions were particularly prevalent among young women and those belonging to poor socio-economic background.

There is no real record of the number of deaths attributed to unsafe abortions in Nepal. However, the government in partnership with WHO has plans to record every maternal death, including those caused by unsafe abortion, through community and hospital-based Maternal and Perinatal Death Surveillance and Response (MPDSR) programme. The programme is still in its infancy, but identifying every unsafe abortion and the social determinants causing it is the only way to prevent these deaths.

Despite comprehensive reproductive right laws, there are still barriers leading to unsafe abortions - the stigma associated with abortion, gender inequality, lack of education, lack of access to services, low socio-economic status and lack of health facilities, among others. Such barriers are present in varying magnitude in various parts of the country leading to incidents like these. The MPDSR programme aims to identify barriers associated with each maternal death and can help guide policy-makers locally and nationally to come up with plans to tackle these.

WHO claims that almost every abortion death and disability could be prevented through sexuality education, use of effective contraception, provision of safe, legal induced abortion, and timely care for complications.

Dr Gupta is with Nyaya Health Nepal, Charikot; guptatk@hotmail.com