Merger policy: Power pressure or need of time?

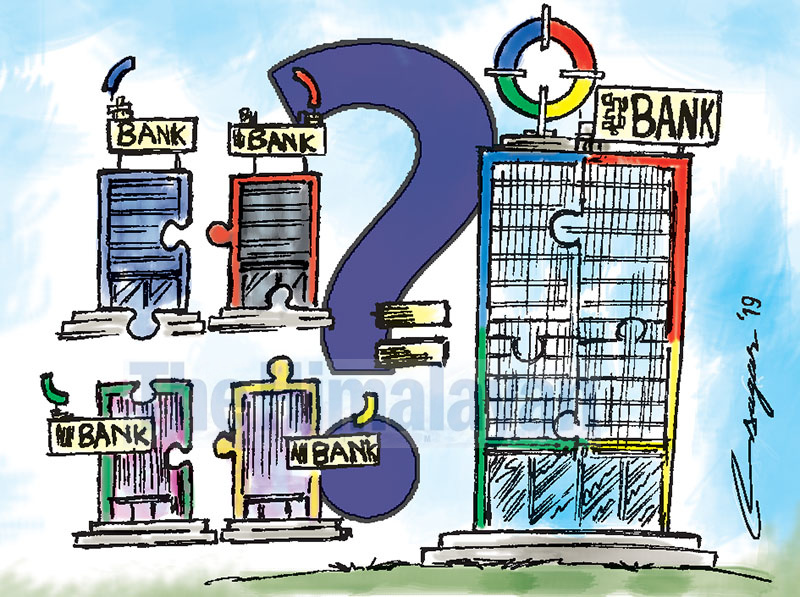

Mergers are underway in almost all countries. However, in Nepal, they are still horizontal rather than vertical. Mergers, therefore, are happening between two or more firms that are operating in a similar kind of business

Nepal Rastra Bank (NRB), the central bank, recently issued a new monetary policy for the fiscal year 2076/77 B.S. Along with addressing a number of other issues, the new monetary policy most notably puts pressures on the commercial banks to go for a merger.

Unlike the capital increment pressure in the previous years, this pressure to merge does not have a yearly deadline.

However, the Governor of Nepal Rastra Bank has been urging the management of commercial banks to merge as early as possible.

In the past, Nepal’s central bank had also explicitly issued orders to all Banking and Financial Institutions (BFIs) to merge as early as possible, and do so by sending a letter to the NRB requesting a merger with some other financial institution within a given period of time.

A merger can be defined as a voluntary agreement between two existing companies or legal entities to fuse on largely equal terms and become a new, larger entity.

Banks normally do this by pooling their assets and liabilities to become one stronger and bigger bank, which can have a significant impact on financial markets. Such amalgamations and acquisitions are commonly carried out in order to expand into a new segment or gain market share, all of which serves to increase the shareholder’s value.

NRB’s definition of merger takes into account capital strength and managerial capability.

Studies of the circumstances prior to and following the mergers reveal that the impetus for the mergers in Nepal was based on the need to increase the paid-up capital, expand the operational area and to decrease horizontal competition.

It is generally accepted in the relevant fields of study that Nepal’s financial market is relatively organised in comparison to other sectors.

Therefore, the government might have tried to adhere more closely to the World Bank’s directions to seek more assistance.

With this in mind, the NRB took the policy of consolidation as one of the tools to enhance the capital base of the commercial banks.

Mergers are rampant in the world’s financial service industry. There is a colloquial phrase ‘too big to fail’. If a big bank went bankrupt, the whole country’s economy could collapse. The US experienced such a phenomenon a couple of years ago, which subsequently drove the world’s economy down with it.

However, the banks in Nepal are not big enough to have such an impact. In comparison to the bigger banks of the world, Nepal’s numbers are trailing by a significant margin, with meager assets and liabilities. Such a situation does not favour mergers.

Merge and mergers have been very common words in the financial industries of Nepal.

This concept became commonplace when financial sector policies, regulations and institutional development were refreshed in the 1980’s.

Following that period, the central bank of Nepal planned to improve the overall health of all financial sectors by introducing laws for mergers in 2011.

This could be done based on Article 177 of the Company Act (2006), and Article 68 and 69 of BAFIA (2006), which made it possible to put pressure on all BFIs to merge, and served as a panacea for the overall development of the country.

One believes that merger was not a choice of Nepal Rastra Bank, but a necessary strategy to increase the capital and strengthen the BFIs’ capacity to face the competitive market.

The NRB is now provoking the BFIs to acquire strength among themselves through mergers. Once merged, it will cut administrative costs, reduce unhealthy competition, curtail the liquidity crunch, prevent bad debt and thereby uplift profit.

NRB policies will also help to open the door for foreigners to enter the banking sector under joint ventures.

Though the NRB has been able to establish a legal base, its pressurisation does not show any financial or technical proof.

After the restoration of democracy in 1990, Nepal introduced the merger policy, especially for BFIs.

However, liberalisation and reform practices were initiated prior to that.

During that time, the World Bank’s Structural Adjustment Programme (activities) also vitalised the BFIs to adopt conciliatory schemes one way or the other.

The NRB, in association with the Nepal government, was made strong on the regulatory path.

The practice of mergers, especially in the financial sector, is underway in almost all countries.

However, mergers in Nepal are still horizontal rather than vertical.

Mergers, therefore, are happening between two or more firms that are operating in a similar kind of business.

In connection with this policy, almost all the BFIs are now being forced to merge irrespective of whether it impacts them positively or negatively.

Such a forced measure may not be good for all, since their establishment and operation happen in different situations, that is, a wide range of assets, people’s financial health, and the need of time and influences of the promoters on the policy are involved. NRB must look at these realities before its merger decision.

Former bureaucrat Pokhrel is a freelance economist