Money from informal channel rules the roost in election campaigns

Kathmandu July 22

Nepalis often joke that people, who have amassed wealth through illegal means, sleep on piles of cash, as they cannot park money in banks due to fear of getting caught. It appears the comment made in jest holds some water.

Take the source of money used in election campaigns as a case in point.

Nepal held provincial assembly and federal parliamentary elections on November 26 and December 7. A total of 3,238 candidates took part in provincial assembly elections and 1,944 candidates contested the federal parliamentary polls.

Each federal parliamentary election candidate spent Rs 10.1 million on average during elections and average spending of each provincial assembly election candidate stood at Rs 8.1 million, according to the report published by the Election Observation Committee Nepal (EOCN) last week. This means candidates spent around Rs 45.9 billion during provincial assembly and federal parliamentary elections.

Almost 94 per cent of this money, according to the report, was spent on election campaigning, which intensified from mid-November. Had all of these funds come from the banking system, money would have been withdrawn from accounts, significantly reducing the stock of deposit at banking institutions.

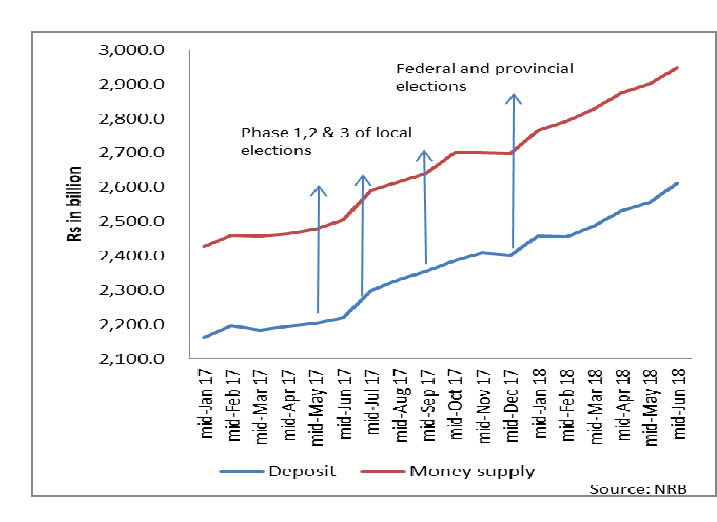

Deposit of banks and financial institutions did fall by Rs 7.2 billion during the one-month period between mid-November and mid-December when polls were held, whereas monthly deposit growth rate hovered around Rs 28.2 billion in the first 11 months of the last fiscal, show data of Nepal Rastra Bank. But the slump in the deposit was small considering candidates’ campaign spending of around Rs 45.9 billion.

As a result, it did not have a great impact on money supply during the period.

The marginal reduction in deposit stock in the mid-November to mid-December period implies a sizeable portion of funds spent during election campaigns came from the informal channel, at least two economists that THT talked to said on condition of anonymity.

This lends credence to rumours that people are stashing cash at home or, as some bankers said, in private lockers in banks.

Generally, people who have amassed wealth through corruption, smuggling or other illicit activities stash cash outside banking institutions. For this group, parking money in banks is out of the question because scrutiny on money flowing through suspicious sources has gone up since the global move to curb money laundering and terror financing intensified several years ago.

But when money stored outside the banking channel is used in economic activities, such as hiring vehicles, microphones and speakers during election campaigns; purchasing T-shirts, flyers and advertisement slots in media; or providing meals and drinks to supporters, a sizeable portion of funds enters the formal system because vendors do not consider it safe to hold on to cash and park earnings in banking institutions.

“It should not take more than a month for such money to enter the banking system because even places where moderate commercial activities take place have access to banks,” said Sanima Bank CEO Bhuvan Kumar Dahal.

Did this happen following Nepal’s recent elections?

Deposit collection did surge by Rs 55.3 billion in the one-month period right after elections, which prompted money supply to grow by Rs 67.5 billion in that period, according to central bank data.

But there is a catch.

“Deposit stock generally grows in mid-January because that’s the time when most of the banks make a quarterly interest payment to depositors,” said Dahal.

Cumulative deposit of banks and financial institutions stood at Rs 2,402.1 billion as of mid-December. So, the interest payment of even one per cent would have increased deposits by Rs 24 billion in that period.

But mid-January is also the time when 40 per cent of annual income tax has to be paid to the government, which results in withdrawals of around Rs 60 billion.

Despite this, deposit grew by Rs 55.3 billion in that period, which indicates a sizeable portion of funds spent in elections did enter the banking system.

Also, currency in circulation fell by Rs 2.9 billion during that period, which indicates money, previously stashed outside banking institutions, was channelled to the banking system.