Understanding Japanese culture through humour

Kathmandu

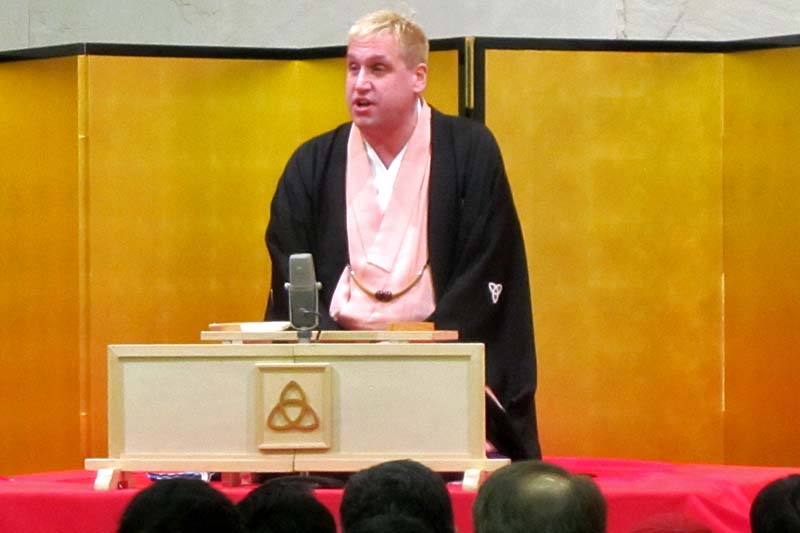

A raised platform is covered in red with a cushion on it and a tiny table hidden by a separator. The audience, waiting silently for the performance to begin, was veiled in a dim light. Soft music played on. The music got stronger as the Rakugo master Katsura Sunshine entered the hall, and the light got brighter. Sunshine gently shone on the stage. He squatted gently but geared up the show abruptly with power monologue pushing his audience into amusement.

Rakugo, organised by the Japanese Embassy, warmed the audience with comic blows on a damp and cold day of January 27.

Sunshine made a quick survey of audience that showed only a couple had seen a Rakugo performance before. With this fact in mind, he explained the rituals of a Rakugo performance. Believed to be a tradition of over 400 years of comic story telling in Japan, Rakugo features minimalistic performance art with a lone storyteller dressed in kimono and equipped with only a hand fan and a hand towel as props.

Sunshine was in black kimono. The preceding monologue explained how Sunshine, a Canadian, could speak Japanese a little without learning at all. The audience burst into laughter on knowing how the prolonged pronunciation of some English words made him able to get the food he wanted. Another material he presented was about 47 different polite expressions in Japanese to express gratitude. He compared some of them and the conclusion was — the longer the phrase is, the more polite the expression would be!

He made various characters on stage but Sunshine differentiated them by moving his head from left to right or vice versa, as well as with a subtle change in tempo, intonation, posture, gesture et cetera. And while hearing him pronounce a very long name of a boy with different tempo in different situations, it sounded as if he was chanting a very long mantra. It was even funnier with punch lines like "the school time was already over before his mother could make the boy with the very long name wake up". Sunshine ended the performance with a zoo story, a relatively longer story that was full of comic plots.

"Why do you tell stories?" when asked, Sunshine answered with a smile, "First, I tell stories to make people laugh and, second, to provide them a window to the Japanese tradition."

The answer provides us a window to look at some dying traditions of storytelling in Nepal: some of them like Sarangi and Hudke are on the verge of extinction, and some others like Baikan Kanegu (said to be highly ritualised storytelling form among Bajracharyas) are almost extinct. Stories make things easier to understand and easier to remember as well. Beyond amusement, stories bring the whole tradition, history and philosophy of a nation and its people alive from generation to generation.

(The author is a dramaturge at Theatre Village)