Building back better: Time to act on landslides

It’s not enough simply to provide vulnerable families with seeds for crops, and feed and shelter for their animals—although that’s critical in the short term. We must also begin emergency rehabilitation work on landslides, to help these farmers build back better after this disaster

Vulnerable farming families in Nepal’s hills have already been through enough in the last couple of months. The six rural districts of Sindhupalchowk, Dhading, Dolakha, Gorkha, Rasuwa and Nuwakot bore the brunt of the quakes. Locals lost family members, homes, crops, seeds, livestock, and vital irrigation infrastructure.

Yet significant dangers still lie ahead for many of these farmers. As this newspaper has reported, the earthquakes have already triggered thousands of landslides, costing more lives and causing fresh damage. Many more landslides are expected during the monsoon. Some families are being relocated, to reduce the risk in the short-term. In the longer term, significant landslide stabilization and prevention work can be carried out to increase the resilience of these communities. Now is the time to be planning and starting early recovery and rehabilitation work. There’s no doubt these needs remain urgent. In the six worst-affected districts alone, food insecurity and poor nutrition are on the rise. Around one in four of these households are headed by women, with many men working overseas to help support their families. These women and their children are particularly vulnerable to food insecurity; they’re more likely to try to cope with natural disasters by eating fewer meals, or selling valuable assets such as farm tools to buy food. FAO has already reached 90 000 vulnerable farming households with the support of Italy and Belgium, providing rice and vegetable seeds, animal feed supplements and airtight grain storage bags. With additional support from Norway and Canada, we will reach more vulnerable farmers to help stave off the threat of prolonged food insecurity facing 900 000 people.

At the same time, working on landslides is at the heart of the principle of ‘build back better’, which was repeatedly emphasized at the International Conference on Nepal’s Reconstruction. It is also consistent with recommendations on the environment and forestry in the Government’s Post Disaster Needs Assessment.

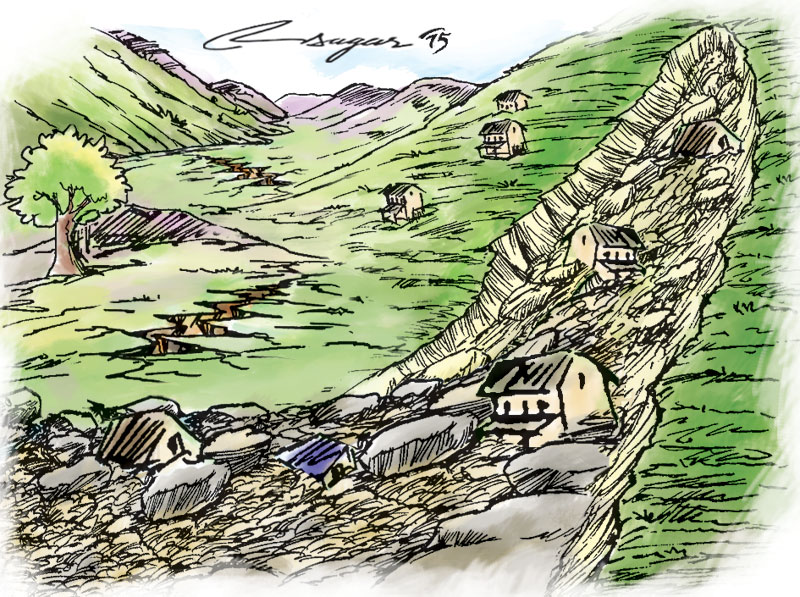

To give a clearer idea of the scale of the landslide threat, the global scientific partnership Earthquakes without Frontiers has mapped landslides triggered by the earthquakes, using satellite imagery.

Thousands of landslides have been reported to date, most of them in the six worst-affected districts.

Beneath the ground’s surface, the geological force has triggered other massive landscape changes that communities don’t yet understand. For example, farmers in Dolakha district have noticed water disappearing into the ground, as soon as they watered their rice terraces. Some springs have dried up, while others have suddenly filled with water. The landslides alone cover such a huge area and in such difficult terrain that the problem might seem insurmountable. But we know from experience in other parts of the world that, with the right measures, we can stabilize landslides and reduce the risk of future disasters. In Nepal, FAO can apply this experience and work with partners to help ensure farmers are less vulnerable to landslide risks in the future. FAO is planning to identify and stabilize critical landslides that have impacted on farmland and irrigation systems in the six worst-affected districts. This could include planting deep-rooted and fast-growing trees and bushes; installing cages full of stones, known as gabions; or building small, temporary ‘check’ dams to control water flows.

FAO is also planning to identify and assess major land cracks in the six districts. The smaller cracks will be sealed off and the larger cracks monitored for any movement, with the help of local communities.

Of course, some landslides are too far underground for these measures to be effective. But for landslides closer to the surface, we know they can work. We also know what will happen if we do nothing to address landslides. More irrigation channels will be blocked, cutting entire communities off from critical water supplies. More agricultural land will be damaged by falling boulders, trees and other debris, reducing food production. We could also see a mass displacement of families, putting huge pressure on farmland and other communities further down the hills. It also makes good financial sense to act now on these landslide threats in Nepal, rather than later. Nepal is already prone to landslides. When you add the predicted effects of climate change, including more extreme rainfall events, the threat increases even further. At this point, the cost of any action will be much higher.

For now, it’s the most vulnerable farmers who are paying a heavy price, in these volatile hills. Many families are sheltering under tarpaulins, in cowsheds that survived the earthquakes, or in plastic tunnels normally used for growing vegetables. Some have no clue how they will afford to rebuild after the monsoon, but for now, they wait. It’s not enough simply to provide these families with seeds for crops, and feed and shelter for their animals—although that’s critical in the short term. We must also begin emergency rehabilitation work on landslides, to help these farmers build back better after this disaster. With more urgent support from international partners, we can increase the resilience of these communities and help them cope better with future crises.

Dr Pipoppinyo is Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) Representative in Nepal