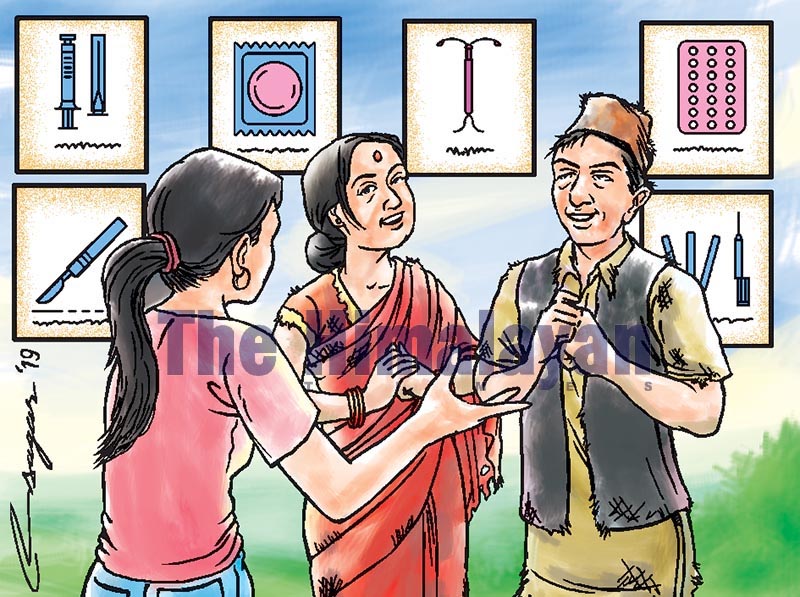

Family Planning: Needs priority for left behind

Time has come to implement a user-centric FP programme that emphasises resources and efforts to deliver information and services fit for special groups like adolescents, post-partum, poor, less educated and hard to reach areas

Family planning (FP) programmes started in the developing countries in the 1960s to reduce rapid population growth as well as fertility so as to match the resources with population growth. But now, the FP has changed its identity and roles. Many international treaties and conferences have accepted FP as a fundamental reproductive health right of individuals and couples. FP is a key element in improving the quality of life for families and communities. FP saves lives of women, neonates and children by allowing women to delay motherhood, space births, avoid unintended pregnancies and abortions, stop childbearing when they have reached their desired family size, and prevent the spread of HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases.

In addition, FP is an investment in future prosperity and is one of the most cost-effective health interventions in the developing world. Contraceptive use helps couples and individuals realise their basic right to decide freely and responsibly if, when and how many children to have. FP can help to break the vicious cycle of poverty and poor quality of life of especially the poor and marginalised communities, as having many children can mean fewer resources (money, time, and attention) invested in each child. Unfortunately, use of contraceptive is less and the unmet need is high among these groups.

In Nepal, the concept of family planning was pioneered by the Family Planning Association of Nepal in 1959. During the 1970s, the fertility rate and population growth were high. It was assumed then that if population growth could be controlled, there would be faster development. So, the FP programme tried to motivate people to accept family planning methods, especially voluntary surgical contraception for those couples with a large family size.

In 1987, the government made a major decision to integrate health services including family planning. At present, FP is an integral part of government health services, provided through federal, provincial and district hospitals, primary health centres, health posts, peripheral level outreach clinics, health workers and volunteers. In the government sector, FP is available free of cost at all levels, however, a health facility managed by local NGOs charge minimum fees to recover their cost.

Nepal has made substantial achievement in reducing fertility, unintended pregnancy and unmet need of family planning. The fertility rate declined from 6.3 in 1976 to 2.3 in 2016, unintended pregnancy declined from 37 per cent in 1996 to 19 per cent in 2016 and unmet need declined from 31 per cent in 1996 to 24 per cent in 2016. Use of contraceptive (any method) increased from 3 per cent in 1976 to 53 per cent in 2016. However, the situation is still not satisfactory when compared to other countries.

The migration pattern of the country has affected the increasing trend in family planning use in Nepal. As per the recent Nepal Demographic Health Survey, 2016, 34 per cent of currently married women and their husbands are separated or do not live together at home due to migration. When husband and wife do not live together there is no need to use contraceptive methods. Due to this factor, contraceptive prevalence rate in Nepal is not increasing compared to the trend in the 1990s. This has created some dilemma in the FP programme of Nepal.

The current progress in family planning is also not even. The fertility rate is much higher among certain minority ethnic groups like the Muslim and Dalits, poor wealth quintiles, rural areas and illiterate women. Use of contraceptives is also very low among these groups. In addition, unmet need of family planning is high among the adolescents, post-partum mother and women living in rural areas. Among individuals and couples who use contraceptive methods, more than 50 per cent discontinue within one year. Teenage childbearing is high (33%) among women with no education and low (7%) among those with an SLC or above. This suggests there are still many people who are left behind from the benefits of FP.

Time has come to implement a user-centric programme, which emphasises resources and efforts to deliver information and services fit for special groups of people, like adolescents, post-partum, poor, less educated and hard to reach areas. Poor and marginalised people in the rural areas are mostly concerned about their daily labour as a means to survive and lack exposure to FP education and the practical advantages that it could have on their harsh living conditions and their quality of life.

Considering these circumstances, the FP programme should be implemented in such a way that activities are directly related to them, their communities, their lifestyles and the local situation. In addition, information, counseling and services should be provided with respect and dignity. Most importantly, they should understand the benefits of FP to improve their personal and family life, breaking poverty and improving the quality of life. When they see information and services near their community and understand that it helps their life, they will start to take an interest, listen more and use the services. Then it will help to achieve the overall goal of sustainable development goal, which aims at “no one be left behind”.

Shrestha works in sexual and reproductive health