Metaphors in city planning: Connecting with people’s beliefs

Despite the intense transformations that the Valley’s traditional towns have seen, what distinguishes them from the structures of today’s cities are the “mentally internalised” urban structures derived from traditional “metaphors”

New towns and cities are emerging across the country, as modern development penetrates the remote and largely rural landscapes of Nepal. Generally, the settlements remain organic/ casual rather than consciously structured. Modern urban planning initiatives in Nepal have generally been small-scaled and piece-meal projects, limited to geometric grid-plans of “Ghaderis” and access roads.

As generations of master plans have been prepared since the 1950s for the Kathmandu Valley, by national and international experts, the largest metropolis has mushroomed into an enormous single sprawl. None of these master plans seems to have made any decisive impact on the Valley’s urban landscape. The urban landscape continues mutating organically into a landscape of individual rather than collective actions. This has continued to perplex the “scientific” city planner.

The simplistic road-grid and “Ghaderi” approach to the new planning projects of the Kathmandu Valley, as well as other emerging towns in Nepal, have also been perceived rather suspiciously by the landowners, whose land is acquired for the projects. Lacking a more “complete” image of the future city, the inability of these plans to project new aspirations have given rise to suspicions of a “land grab”, which have led to a negative perception about the term “planning”.

In the newly created federal administrative structure of Nepal, the entire country has been divided into municipalities around emerging towns and cities. Considering the low percentage of urban population in Nepal, this policy seems to have been put in place to preempt the negative impacts of rapid urbanisation.

Implementation of comprehensible urban structures becomes strategic for the development of these towns and cities in the future. A comprehensive urban structure, which is clearly understood by all citizens, facilitates many things: a strong sense of place, identity and community formation, efficient functioning and a strong sense of ownership towards the city.

A strong sense of ownership plays a critical role in the environmental quality of a city, and also determines the effectiveness of political governance. We all are familiar with the exodus of humanity that leaves the Kathmandu Valley during Dashain/Tihar, estimated at almost two million people. For a majority, the city remains a place to consume the windfall of modern development rather than “to own” and call “home”.

Today, the places, which evoke a strong sense of community, urban culture and place, are Kathmandu Valley’s traditional/ historic towns and cities. Despite the intense transformations that these places have undergone in recent decades, what distinguishes them from the banal road-grid urban structures of contemporary cities are the “mentally internalised” urban structures derived from traditional “metaphors” of towns and cities.

There has been a long history of structuring town and cities in the Kathmandu Valley based on “metaphors” drawn from Hindu-Buddhist scriptures, which translated into diagrams gave the town its urban structure in space. We know of Patan being planned as a Dharmachakra; Kathmandu as Chandrahrasa (sword); Kirtipur as Swastika; Deopattan as Karmuka (bow and arrow); Bhaktapur as a Yantra locating the Astramatrikas; and Bishalnagar as a Mandala.

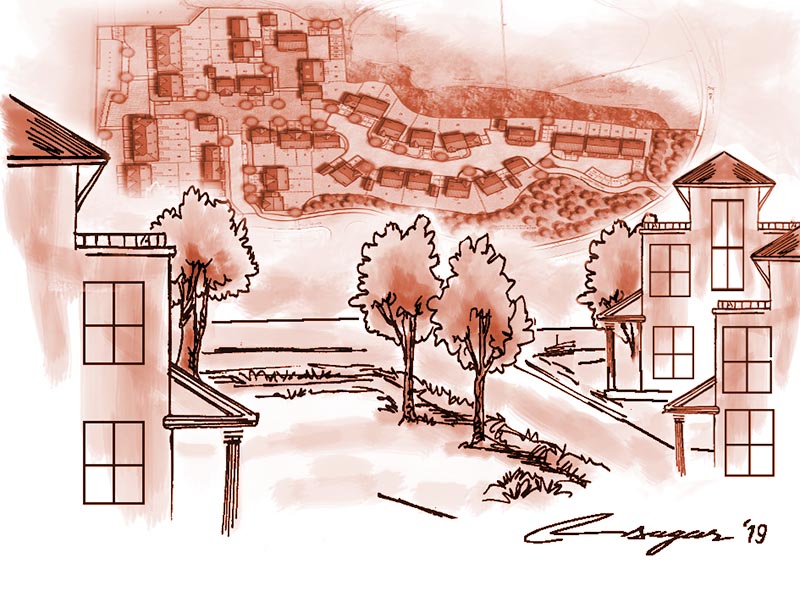

Historically, these metaphors were deployed as diagrammatic overlays over existing settlements to restructure cities for future development. Over time, these metaphors got embedded in the imagination of the city’s socio-cultural life. Once the basis for the city’s built fabric was clearly established, culturally-rooted sustainable architecture forms evolved.

Originating from Hindu-Buddhist scriptures, these metaphors formed a strong relationship with the citizen’s belief system, “Aastha”. In recent years, we have seen the increasing use (misuse) of Vaastu rules in the planning of modern scientifically based buildings, demonstrating a need to connect what people build with their “beliefs”.

In a similar approach, the renowned American city planner, Kevin Lynch, stressed the significance of mental mapping of urban structures (visuo-spatial representation of the city) in planning healthy urban environments, drawing on research in cognitive mapping. He invented the term ‘imageability’ to describe the degree to which the urban environment can be perceived as a clear and coherent mental image.

City planning is first a socio-cultural and political endeavour, which engages technical practices later for its physical realisation. Concepts, which engage the citizen’s “aastha”, become significant in planning socio-culturally viable cities today. While for modern cities to function efficiently, scientific and quantifiable logic is important; in the absence of a “larger idea” with which citizens can connect, conventional city planning remains abstract and inaccessible.

To connect future city planning once again to people’s comprehension and beliefs, we need to develop new “metaphors” based on local history, culture, lores, natural and cultural assets, geography as well as the pulse and potentials of the emerging towns and cities in Nepal, metaphors through which actual physical urban structures can be internalised in the citizen’s imagination.