Solar energy promotion: Learn from Bangladesh

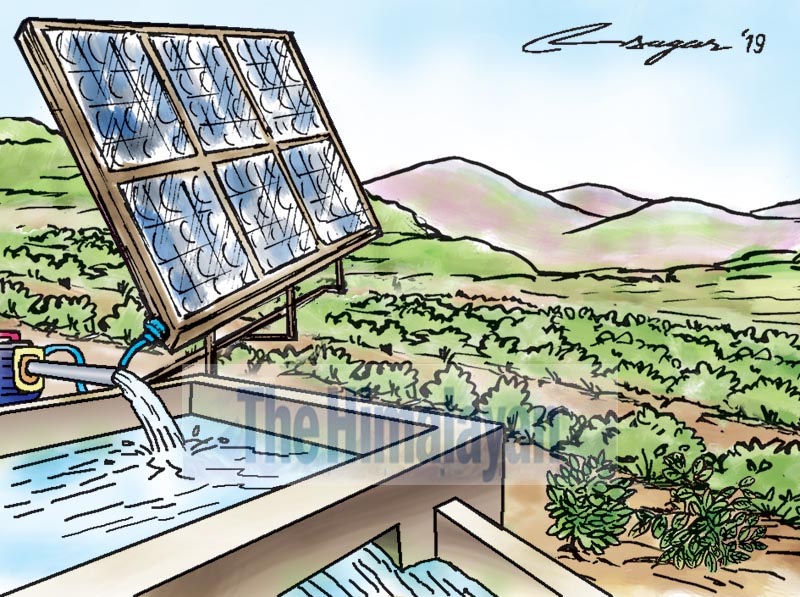

As solar-generated electricity is projected to see a 59 per cent cost reduction by 2025 compared to 2010 prices, subsidies would then no longer be the deciding factor for the use of solar water pumps

Nepal and Bangladesh are not only close neighbours, they also share many similar development challenges.

Irrigation is a priority of Bangladesh, which keeps a large number of pumps in operation. Most of them run either on diesel or grid electricity, with a negligible number of pumps operating on solar energy. Currently about 1.4 million diesel-operated pumps are said to be in use for irrigation in Bangladesh. In addition, there are 270,000 grid-connected electric irrigation pumps. The penetration of Solar Water Pumps (SWPs) is, however, insignificant.

Except for large irrigation facilities, farmers have four options to irrigate their land: rainwater requiring no technological interventions; electric pumps using grid electricity; diesel-powered pumps; and SWPs.

A special provision has been made to provide subsidised electricity for irrigation. Distribution companies authorise short-term, or seasonal, grid connections to the farmers. Short-term connections are provided for four months from early November, and provide electricity for irrigation purposes during the winter cropping season. Electricity is supplied typically for 10 hours per day on the distribution feeders, which are separated from the domestic supply feeders. Farmers are responsible for connecting the electric wire required for operating their pump to a coupling point identified by the distribution companies, usually the nearest distribution transformer. Farmers are also responsible for removing the connection after four months when the temporary electricity supply ceases.

The cost of irrigation ranges from around 800 to 1,200 Bangladeshi taka (BDTK) per bigha under the subsidised electricity tariff rate, about half of what the domestic electricity tariff would entail.

A comparison between the operating cost of running a diesel-powered pump and a SWP is important because the latter is meant to replace diesel pumps. It is found that an unsubsidised SWP costs even less than irrigating the same amount of land by a subsidised diesel pump in the long run. Bangladesh provides subsidy - around 30 per cent - on diesel. If the subsidy on diesel is lifted, then the SWP becomes even more cost competitive. The cost of irrigating one bigha of land is around 4,000 takas for a diesel pump, and around 2,500 takas for a SWP.

In case of subsidised electricity, it becomes the most cost-effective option for the farmer. Maintenance is convenient as the local technicians are familiar with the technology. The only difficulties are related to coupling and decoupling of the electrical wire, which may pose significant life safety hazards. So the SWPs will have to compete with the grid-electrified pump irrigation.

The low deployment of SWPs is, however, not only because of their lack of price competitiveness compared with diesel. The barriers to large-scale dissemination of SWPs in Bangladesh are related to policy, information (awareness) and market supply chain, including the financing mechanism.

Solar energy is expected to become the energy of the future. The SWP has emerged as a promising technology to expand irrigation and is being deployed rapidly across the world. Lessons from other parts of the world, however, show that there is always a slower deployment rate of the SWP system mainly because of its high upfront cost and lack of awareness on the part of the users as well as policymakers. National policies generally do not favour SWP deployment on a large scale because it generally needs to compete with the conventional practices and lately because of increasing access of the national grid.

The International Renewable Energy Agency is projecting a 59 per cent cost reduction for solar-generated electricity by 2025 compared to 2010 prices. As investment costs for SWPs are coming down, subsidies would then no longer be the deciding factor for both big and small farmers.

The Bangladesh Rural Electrification Board (BREB) recently initiated a pilot programme to disseminate 2,000 SWP systems by the year 2020 and later scale up the programme with a target of around half a million SWPs. Solar energy will be the game changer in Bangladesh because its electricity demand is huge, which cannot be fulfilled by just relying on indigenous fuels, mainly gas, and limited hydropower.

Nepal’s energy needs are peculiar because of its scattered settlements. SWPs can help in the irrigation of high value crops. A solar pump can alleviate the water problem for drinking and irrigation. Nepal is also considered as a pioneer in renewable energy development, including solar water pumping for irrigation and institutional uses, including drinking water.

Grid electricity has reached close to 80 per cent of the population in Nepal. Nevertheless, SWPs are compatible not only to areas where the grid has not reached but also those areas with a grid, where a SWP is cost effective in pumping water on a small scale.

Nepal is considered to have a better institutional and market structure, which can help large-scale SWP dissemination. What is important for Nepal now is to have a policy guideline with a long-term vision, a sustainable business model and institutional clarity in supporting large-scale deployment of SWPs. It will help in an energy mix and ultimately enhance energy and food security.

Adhikari served as a consultant to Bangladesh Rural Electricity Board