9/11 suspects pose legal risks

WASHINGTON: In the biggest trial for the age of terrorism, the professed 9/11 mastermind and four alleged henchmen will be hauled before a civilian court on American soil, barely a thousand yards from the site of the World Trade Center's twin towers they are accused of destroying.

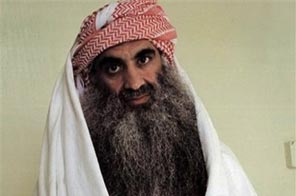

Attorney General Eric Holder announced the decision Friday to bringKhalid Sheikh Mohammed and four others detained at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, to trial at a lower Manhattan courthouse.

It's a risky move. Trying the men in civilian court will bar evidence obtained under duress and complicate a case where anything short of slam-dunk convictions will empower President Barack Obama's critics.

The case is likely to force the federal court to confront a host of difficult issues, including rough treatment of detainees, sensitive intelligence-gathering and the potential spectacle of defiant terrorists disrupting proceedings. U.S. civilian courts prohibit evidence obtained through coercion, and a number of detainees were questioned using harsh methods some call torture.

Holder insisted both the court system and the untainted evidence against the five men are strong enough to deliver a guilty verdict and the penalty he expects to seek: a death sentence for the deaths of nearly 3,000 people who were killed when four hijacked jetliners slammed into the towers, the Pentagon and a field in western Pennsylvania.

"After eight years of delay, those allegedly responsible for the attacks of September the 11th will finally face justice. They will be brought toNew York — to New York," Holder repeated for emphasis — "to answer for their alleged crimes in a courthouse just blocks away from where the twin towers once stood."

Holder said he decided to bring Mohammed and the other four before a civilian court rather than a military commission because of the nature of the undisclosed evidence against them, because the 9/11 victims were mostly civilians and because the attacks took place on U.S. soil. Institutionally, the Justice Department, where Holder has spent most of his career, has long wanted to reassert the ability of federal courts to handle terrorism cases.

Lawyers for the accused will almost certainly try to have charges thrown out based on the rough treatment of the detainees at the hands of U.S. interrogators, including the repeated waterboarding, or simulated drowning, of Mohammed.

The question has been raised as to whether the government can make its case without using coerced confessions.

That may not matter, said Pat Rowan, a former Justice Department official.

"When you consider everything that's come out in the proceedings at Gitmo, either from the mouth of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and others or from their written statements submitted to the court, it seems clear that they won't need to use any coerced confessions in order to demonstrate their guilt," said Rowan.

Held at Guantanamo since September 2006, Mohammed said in military proceedings there that he wanted to plead guilty and be executed to achieve what he views as martyrdom. In a letter from him released by the war crimes court, he referred to the attacks as a "noble victory" and urged U.S. authorities to "pass your sentence on me and give me no respite."

Holder insisted the case is on firm legal footing, but he acknowledged the political ground may be more shaky when it comes to bringing feared al-Qaida terrorists to U.S. soil.

"To the extent that there are political consequences, I'll just have to take my lumps," he said. But any political consequences will reach beyond Holder to his boss, Obama.

Bringing such notorious suspects to U.S. soil to face trial is a key step in Obama's plan to close the military-run detention center in Cuba. Obama initially planned to close the prison by next Jan. 22, but the administration is no longer expected to meet that deadline.

Obama said he is "absolutely convinced that Khalid Sheikh Mohammed will be subject to the most exacting demands of justice. The American people will insist on it and my administration will insist on it."

After the announcement, political criticism and praise for the decision divided mostly along party lines.

Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky said bringing the terrorism suspects into the U.S. "is a step backwards for the security of our country and puts Americans unnecessarily at risk."

Former President George W. Bush's last attorney general, Michael Mukasey, a former federal judge in New York, also objected that federal courts were not well-suited to this task. "The plan seems to be to abandon the view that we are at war," Mukasey told a conference of conservative lawyers. He said trial in open court "creates a cornucopia of intelligence for those still at large and a circus for those being tried," and he advocated military tribunals instead.

But Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Patrick Leahy, D-Vt., said the federal courts are capable of trying high-profile terrorism cases.

"By trying them in our federal courts, we demonstrate to the world that the most powerful nation on earth also trusts its judicial system — a system respected around the world," Leahy said.

Family members of Sept. 11 victims were also divided.

"We have a president who doesn't know we're at war," said Debra Burlingame, whose brother, Charles Burlingame, had been the pilot of the hijacked plane that crashed into the Pentagon. She said she was sickened by "the prospect of these barbarians being turned into victims by their attorneys."

Valerie Lucznikowska, whose nephew died at the World Trade Center, said she wouldn't care if the suspects sounded off in court — as long as the victims' families got to see them put on trial.

"What are words? It was a horrible thing to have 3,000 people killed," she said.

The five suspects headed to New York are likely to face thousands of counts of murder and conspiracy. Mohammed and the four others — Waleed bin Attash, Ramzi Binalshibh, Mustafa Ahmad al-Hawsawi and Ali Abd al-Aziz Ali — are all accused of orchestrating the 2001 attacks.

The government also announced five other Guantanamo detainees, including the alleged mastermind of the 2000 bombing of the USS Cole, Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri, would be sent to military commissions to face charges.

Holder said no decision had been made on where commission-bound detainees would go. A Navy brig inSouth Carolina has been high on the list of sites under consideration.

The actual transfer of the detainees from Guantanamo to New York isn't expected to happen for many more weeks because formal charges have not been filed against most of them.

Other trial locations that Holder considered, including Virginia, Washington, D.C., and a different courthouse in New York City, could end up conducting trials of other Guantanamo detainees later.

The administration has already sent one detainee, Ahmed Ghailani, to New York to face trial.

The four other detainees headed to military commissions in the United States are: Omar Khadr, Ahmed Mohammed al Darbi, Ibrahim Ahmed Mahmoud al Qosi and Noor Uthman Muhammed. Their cases are not specifically connected, but two of them are accused of plotting against or attacking U.S. military personnel.

Barry Coburn, a lawyer for Khadr, called the decision about his client "devastating and shocking."

Khadr "was 15 years old when he was detained in Afghanistan as a child soldier and has been locked away in Guantanamo ever since," he said.