Gates: stop civilian deaths in Afghan

BRUSSELS: The United States and its allies must reduce the number of civilians killed in the hunt for the Taliban in Afghanistan, U.S. Defense Secretary Robert Gates said Friday. He called the civilian deaths "one of our greatest strategic vulnerabilities."

"Every civilian casualty, however caused, is a defeat for us and a setback for the Afghan government," Gates told reporters.

Civilian casualties have been a source of tension between the Afghan government and U.S. and NATO troops. President Hamid Karzai has pleaded with U.S. officials to reduce the number of civilians dying as a result of the fighting.

American officials say that Taliban militants purposely try to cause civilian deaths that can be blamed on U.S. forces in order to turn ordinary Afghans against the international military effort.

Gates said little about the latest high-profile killings, a disputed incident in a western province in which Afghan officials have said that the civilian death toll was 140. U.S. commanders have said they believe no more than 30 civilians were killed, along with 60 to 65 Taliban insurgents.

"We can do better," Gates said.

Gates said preventing civilian deaths is a primary assignment for the American general he picked to turn around the stalemated Afghanistan.

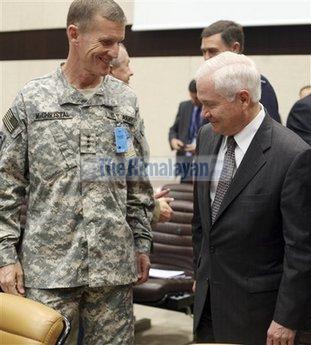

As he headed to his first day on the job in Kabul, Gen. Stanley McChrystal paid a courtesy call Friday on NATO defense chiefs, a gesture meant to acknowledge the alliance's help even as the United States shoulders an ever-larger share of the fighting.

"I assure you that I take the responsibility very, very seriously," McChrystal told the ministers. He was in Brussels for a few hours for an update on NATO activity in Afghanistan.

The alliance has declared the Afghan war its highest military priority, but the fight against Taliban-led insurgents is unpopular in many European nations and several alliance countries are reducing or eliminating their forces.

McChrystal's Army fatigues stood out in a room full of business suits and dress uniforms. The general will be the overall commander for all forces in Afghanistan, including an American force expected to reach 68,000 by the end of this year, and about 32,000 allied troops.

Gates fired his last commander, and has said the war effort lacked focus and resources. He hand-picked McChrystal and named his own top military aide as the general's deputy in one of the clearest signs yet that the Obama administration is gravely worried about the course of the eight-year war.

Gates was in Europe for three days of consultations with NATO allies.

The military has given McChrystal his pick of officers and a free hand to rearrange what many considered an inefficient command structure. The United States is trying to ally NATO concerns about creeping "Americanization" of the war's direction, but will nonetheless install a new hierarchy that more closely resembles the U.S. military machine in Iraq.

NATO Secretary-General Jaap de Hoop Scheffer acknowledged Friday that development is not coming to Afghanistan as fast as the alliance had hoped, but said little about the direction of the overall war in opening remarks to the defense chiefs.

At a farewell news conference as he prepared to leave the top NATO job, de Hoop Scheffer acknowledged the tension within NATO and among European governments over the goal and importance of the Afghan fight. It is easier for him to talk about the development part of the mission, and far harder to explain that "we are there fighting terrorism," and that the stakes are high, he said.

"We cannot afford to lose," he said.

With insurgent violence at its highest point ever, U.S. officials acknowledge they are not winning in Afghanistan. While vastly superior in training and equipment, the combined U.S. and NATO militaries are hamstrung in certain parts of the country by an entrenched and flexible insurgency that relies on low-tech tactics, intimidation and payoffs.

President Barack Obama has promised to make the fight his focus in a way that former President George W. Bush did not. The Afghanistan fight, then going relatively well, became an afterthought in Washington, and always second in line for resources, following the 2003 U.S. invasion and occupation of Iraq.