UN chief no match for Myanmar ruler

BANGKOK: Myanmar's military ruler Than Shwe keeps an iron grip over the nation from a remote capital, guided by deep-seated paranoia about international interference and the popularity of Aung San Suu Kyi.

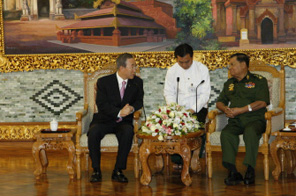

The reclusive 76-year-old acted true to form when he had UN chief Ban Ki-moon come to his bunker-like stronghold Naypyidaw and then kept him waiting overnight for a decision on whether Ban could visit the democracy icon.

There were few surprises when the senior general eventually refused to allow the meeting with Aung San Suu Kyi, citing the fact that she is on trial for breaching the terms of her house arrest.

The junta chief followed his typical pattern of allowing the minimum foreign involvement in Myanmar's affairs, while using high-profile visits to appear as if he was at least listening to international concerns, analysts said.

But at the heart of all decisions taken by the regime -- effectively meaning Than Shwe himself -- is an imperative to maintain the military's power over the impoverished country as it has done for the last four decades.

"Of course they want a good image, that's why they are suppressing the opposition voices and trying to discredit them," Thailand-based political and military analyst Win Min told AFP. "But to maintain power is more important than the image." Than Shwe has increasingly styled himself as a reincarnated king, designating the new capital Naypyidaw, meaning "abode of kings", in a clear expression of his desire to rule in total secrecy.

It also underscored another preoccupation -- astrology. He gave government workers just hours to pack and move from Yangon to the half-built new capital on November 7, 2006, as the time and date had been ordained by astrologers.

Fearful of foreigners and holed up in his remote compound, Than Shwe's isolation now means he has little understanding of the reality facing the people in Myanmar and even less about the outside world.

"He's quite happy to sit up in Naypyidaw and hear his own constructed view of the country presented to him. Wherever he goes it's all laid out for him," said David Mathieson of Human Rights Watch.

The military first took charge of the country post-independence in a 1962 coup, with the current regime toppling previous dictator Ne Win in 1988 after crushing a student-led uprising.

Than Shwe took the helm in 1992. Described by diplomats as taciturn and insular, Than Shwe is a former postman-turned-soldier who fought separatist rebels in a roving psychological warfare unit on his way to the top.

He has used his training to manipulate political adversaries like Aung San Suu Kyi, but also rival generals including his own prime minister, the reformer Khin Nyunt, whom he jailed in 2005.

He later took Khin Nyunt's idea of a seven-step "road map to democracy" to construct his own plan that critics say is aimed at simply retaining power.

The junta held a referendum on a new constitution just days after a deadly cyclone killed 138,000 people in May 2008 and is now planning elections for 2010 that bar Aung San Suu Kyi from standing.

But although his generals have denounced "interference" from abroad over Aung San Suu Kyi's closed-door trial, Than Shwe is not immune to diplomatic pressure.

Ban was able to persuade him to allow in foreign aid following Cyclone Nargis, a chink in the general's armour that allowed the UN chief to think he might be able to extract concessions on his latest visit.

Yet UN officials said the junta's reaction to Ban's latest proposals -- such as the release of political prisoners including Aung San Suu Kyi -- met with stiff resistance over the course of their two meetings.

Aung San Suu Kyi is the one person whose actions seem to matter to the junta, although mainly because of their loathing and paranoia about the threat her popularity poses to their rule, said Mathieson.

"They bristle at how popular she is internationally," he said.