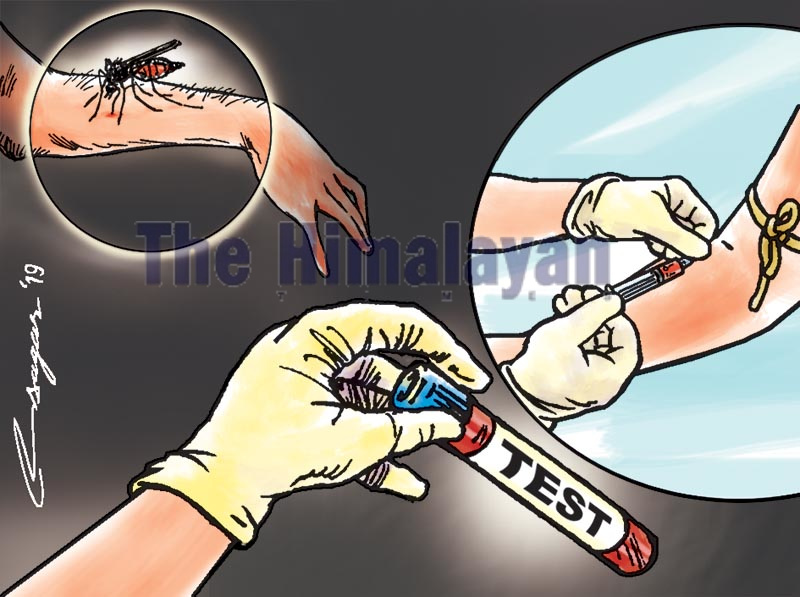

Zika or dengue epidemic? Only tests will tell

Zika or dengue epidemic? Only tests will tell

Published: 09:00 am Nov 25, 2019

Although Zika virus is not yet scientifically reported, the aedes mosquito species, responsible for its transmission, is widespread in Nepal, and therefore, it would not be surprising if Zika virus infections are reported in Nepal Since late May 2019, thousands of patients with dengue or dengue-like illnesses continue to visit different hospitals across the country. Several patients, especially after the Tihar festival, began to show (or are showing) fever along with red eyes (conjunctivitis) and rash. In September, the Epidemiology and Disease Control Division (EDCD) had issued a statement, in which they requested healthcare providers not to use kits for dengue identification due to its unreliable results. Physicians, thereafter were compelled to assume dengue fever in patients based on their clinical presentations and complete blood count (CBC) test results. It is worth noting, however, that the signs and symptoms, including laboratory results, of a dengue virus are very similar to those of a Zika virus. Both dengue and Zika viruses are transmitted by the bite of a same mosquito.The question, then arises “Was it a Zika or dengue epidemic?” High-grade fever, pain behind the eyes, body ache, lower back pain, joint pain, pin-point red rashes, nausea and vomiting are the main signs and symptoms of dengue fever. Symptoms of Zika include mild fever, muscle and joint pain, headache, red eyes, rashes (mostly maculo-papular) and symptoms usually lasting for a week. Some of the patients had developed rashes immediately followed by mild fever, which is consistent with Zika virus infection. Redness of the eyes, one of the main symptoms of Zika virus infection, has been seen in several patients, which was almost absent until the Tihar festival. Both confluent petechial (pin-point red rash) and maculo-papular rashes were observed among febrile patients. The first Zika case was reported in India in 2017. In 2018, the Indian National Centre for Disease Control reported 150 confirmed Zika infections from Rajasthan state, 130 cases from Madhya Pradesh and one from Gujarat state. At least 63 cases involved pregnant women. Scientists believe that Zika virus may have silently spread to other parts of India. Possible introduction of Zika virus through infected Nepalis or Indians in Nepal is a matter of great concern.Tens of thousands of people from either of the countries cross the border every day for shopping or in pursuit of better work. Thailand and Malaysia are other countries from where Zika could be introduced into Nepal through travellers or migrant workers. Malaysia is the largest destination for Nepali migrant workers, accounting for 40.9 per cent. Malaysia reported its first case of Zika infection in September 2016. In October, the first Zika-infected patient reportedly died of complications this year. In March 2015, a Zika virus outbreak was observed in Brazil. Seasonality of Zika in South Asia is not well understood. Last year, however, Zika virus outbreak occurred during September-October in India. In Singapore, Zika virus outbreak was reported in September in 2016. In Nepal, increasing number of patients with fever, rash and red eyes began to be seen since October-November, which points to the possible existence of Zika virus in Nepal. Zika virus testing was initiated some years ago, unfortunately, it was stopped after some weeks for no reason. Currently, a patient with fever is believed to be infected with dengue virus. Rapid diagnostic test (RDT) kits are extensively used to determine or rule out this virus. Based on the RDT kit results, the government used to announce the total number of cases as well as the trend or distribution of the disease in Nepal. However, several researches have shown that RDT kits display cross reactivity between dengue and Zika viruses. In another words, it is quite possible that those diagnosed as having dengue were actually cases of Zika virus. Moreover, dengue negative cases or dengue like illnesses were never re-tested for other mosquito carrying viruses to identify the cause of the “2019 febrile epidemic”. Microcephaly, in which a baby’s head is much smaller than normal for an infant of that age, is one of the main complications of Zika virus infection. Currently, an unexpected rise in the number of microcephaly cases is not observed in Nepal. Preterm and still birth are other obstetric conditions that have received less attention so far, and are also associated with Zika virus infection. According to a study published in 2013, 14 per cent of babies were born preterm (babies born alive before 37 weeks of pregnancy) in 2010. Stillbirth is as high as 35.4 per 1,000 in rural areas of Nepal. Studies have shown that infection is one of the major causes of stillbirth and preterm birth in Nepal, although no attempt has ever been made to identify the causative agents. It is, thus, worth testing or screening for the Zika virus in women who have a history of stillbirth and preterm birth deliveries. During the “2019 febrile epidemic”, tens of thousands of patients, who had fever, rash and red eyes, visited different hospitals across the country, and were suspected to have dengue fever, although this might not have been the case. Although Zika virus is not yet scientifically reported, the aedes mosquito species, responsible for Zika transmission, is widespread in Nepal, and therefore, it would not be surprising if Zika virus infections are reported in Nepal. Dr Pun is Chief, Clinical Research Unit Sukraraj Tropical & Infectious Disease Hospital