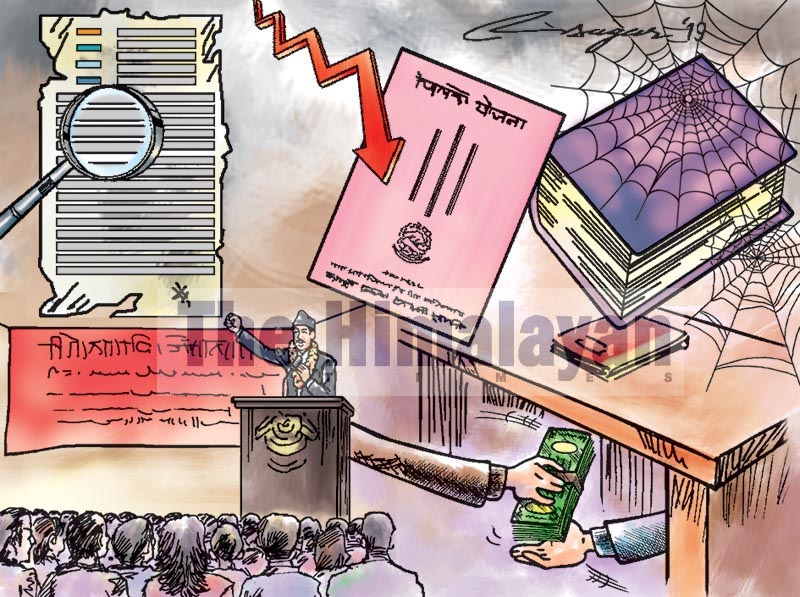

Why plans fail in Nepal: Misplaced orientation at fault

Why plans fail in Nepal: Misplaced orientation at fault

Published: 08:45 am Sep 13, 2019

The planning process is not only centralised but also personalised. Hence, the political leaders and bureaucrats can make the planning wheel move. As a consequence, resources are misused in larger proportions in Nepal Nepal started planned development more than 60 years ago. Currently, we are set to implement the 15th periodic development plan, setting forth various objectives and priorities in accordance with the federal governance process and framework. According to development economists like Michael P Todaro, planned development is an organised, conscious and continual attempt to select the best available alternative to achieve a specific goal. Before the onset and elaborate unfolding of a successive periodic plan in Nepal, it is discussed at different levels, including the National Development Council. The priorities and targets of the development plan are fixed and specified. However, the goals and objectives of the development plans are vague and overambitious in Nepal. The plans try to accomplish too many objectives since the development planners are always tempted to make them look grandiose in design. The gap between plan formulation and implementation is enormous. The national capacity to execute plans and produce appropriate results is starkly poor. This is due to our poor capacity to make the best use of physical, human and fiscal resources. In a least developed country like Nepal, economic planning is deployed as a tool for eliminating poverty, reducing inequality and lowering unemployment. But because of the misplaced orientation of the planning process and attendant constraints like poor quality data, institutional weaknesses, cumbersome bureaucratic procedures, and resistance to innovation and change, planning policies are found contributing unwittingly to the perpetuation of underdevelopment. The philosophy of economic planning can be broadly classified into indicative planning and command and control-based centralised planning. Indicative planning sets the targeted rate of growth for the economy as a whole for a specific time period. In this type of planning, the role of the private sector and civil society is important. The indicative type, free market-based planning is based on the premise that the invisible foot would provide a more powerful kick towards economic development and growth than the visible hand of the central command-based planning. As is known, command and control type centralised planning functions within the hierarchical framework of the state machinery. But Nepal more or less follows the mixed type of planning process, where the role of the state, private and civil sectors has been recognised for development. However, it is envisaged that the development planning process should start with a long-term vision and perspective. The perspective outlook should embody an assessment of the country’s long-term development vision and goal. Then comes the periodic planning process followed by annual planning activity. The total activities of the government should reflect in the plan document. As mentioned above, Nepal has already implemented more than a dozen periodic development plans, but most of them could not achieve their intended goals and targets. The reason why plans for development fail in Nepal has been typically diagnosed by Swedish economist Gunar Myrdal, who earned worldwide reputation for his famous Nobel Prize winning work The Asian Drama. He mentioned that poor technology, underdeveloped institutions for enterprise and development, imperfections in the authority of the government, centralised governance system, corruption, and low efficiency and standards of integrity in public administration were the major impediments to effective implementation of the plans in Nepal. With a view to addressing some of the issues and challenges pointed out above, Nepal initiated institutional measures towards strengthening a decentralised development planning strategy. Currently this has been instituted and consolidated through the constitutional provision within the federal framework, where three tiers – local level, province and federal - of the government formulate plans and implement them accordingly. Each tier of the government has a respective sphere of jurisdiction, and the projects and plans have to be designed and formulated with due adherence to the limits of the jurisdictional authority. However, this has been totally disrespected, with projects evolving at the ward level being shelved at the Gaupalika and Nagarpalika level. Similarly, larger projects of the Gaupalika and Nagarpalika are not entertained by the provinces. The federal government, on its part, overrides constitutional and statutory limits as powerful politicians and bureaucrats introduce their own pet projects to support their respective constituencies. Moreover, constituency development allocations, handled by the parliamentarians, pose a big problem for the coordinated and harmonised framework of the planning process. There is no mechanism and process to strike a linkage between the country’s needs and development planning so that appropriate projects are identified and selected, and resources are allocated accordingly. The planning process is not only centralised but also personalised. The political leaders, bureaucrats and those who can dictate the official channels can make the planning wheel move. As a consequence, resources are misused in larger proportions in Nepal.