Doctors should not rest on their laurels after obtaining degree

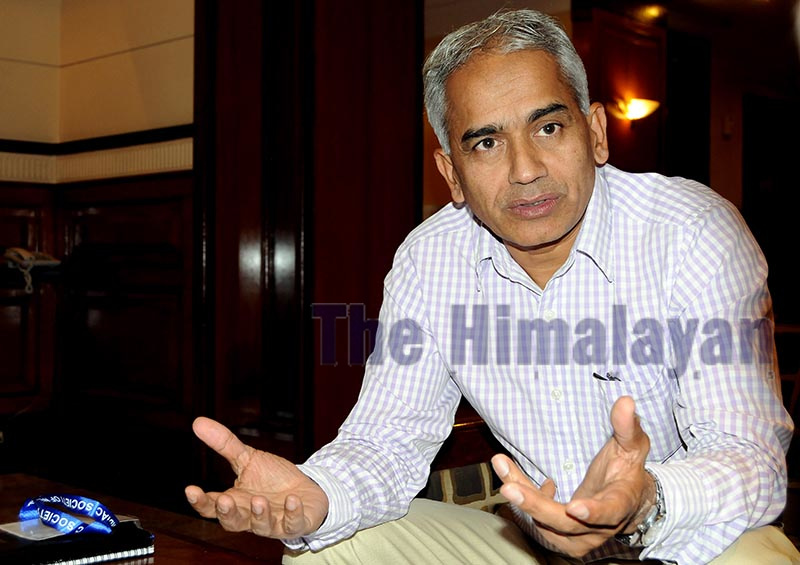

Dr Bhagwan Koirala, a senior cardiothoracic and vascular surgeon, was recently appointed as the chair of Nepal Medical Council, a body that regulates the medical sector and provides licence to doctors to practice medicine in Nepal. He pioneered open heart surgery in Nepal and played a crucial role in establishment of Shahid Gangalal National Heart Centre and Manmohan Cardiothoracic Vascular and Transplant Centre. Sabitri Dhakal of The Himalayan Times met Dr Koirala to discuss the changing roles and responsibilities of the medical council, its future plans, anomalies in the medical sector and reforms required to provide quality healthcare services. Excerpts:

Roles and responsibilities of Nepal Medical Council have changed since the introduction of a new law, haven’t they?

With change in the Health Professional and Education Act, the terms of reference for Nepal Medical Council have changed. The council will no longer look into medical education sector as it falls under the domain of Medical Education Commission. The council’s work is currently divided into three areas: overseeing whether or not doctors are upholding medical ethics; making sure doctors are updated with medical practices; and monitoring safety-related issues in healthcare sector. The council will also conduct licensing examination for medical practitioners. I want to clarify that the council has its limitations and will not regulate works of nurses and technicians working in the healthcare sector. We only monitor works of registered doctors.

How are you planning to steer the council?

One of our main tasks is to provide licence to doctors so that they can practice medicine. We provide licence only to the competent ones. The licensing examination is currently manual and basically tests theoretical knowledge of applicants. We need to introduce competency-based examination. We are also planning to conduct computer-based tests for which we need to strengthen our IT system. We are working on it. Though it will create difficulties, it is necessary for patients’ safety as there are medical colleges where students haven’t got enough practical education.

We are working to enhance skills of doctors so that they can offer healthcare services of international standard. Doctors should be aware about changes in medical theories and new researches being carried out in the field. So, they should study continuously. In this regard, we are trying to implement Continuous Professional Development programme for all registered doctors. If doctors fail to secure required points in CPD programme, their licences will not be renewed. The primary responsibility of producing competent medical practitioners lies with universities and academies. But we are authorised to cross examine their quality, and it’s our duty to make sure they are competent. We will use the principles of educate, empower and enforce to enhance quality of doctors. Doctors should not rest on their laurels after obtaining a degree from a college or a university. They need to keep themselves updated. We also intend to focus more on doctor’s works, mistakes made by them, and patients’ complaints. The grievances of the public will be seriously investigated.

Some of the doctors are rejecting the concept of CPD. What is your take?

Doctors should ask whether the programme is beneficial for them, patients and the country. If the answer is yes, we all should support this cause. Many doctors are not happy with this programme because it forces them to attend conferences and meetings to score points. We should make sure that all the doctors, specially those working in remote areas, gain access to these conferences and meetings. So I don’t think this is a big issue. The council is training the trainers for CPD programme in all provinces.

How challenging is it to make Nepal Medical Council credible?

It is challenging to meet all expectations of the public. As I told you earlier, we have limitations. But we would like to work with other stakeholders to bring about changes. These changes may not be visible immediately because reform is a continuous process. We will set certain performance indicators which will look into complaints that have been handled, decision-making process, delivery of justice to people, and implementation of CPD programme. We are trying to improve the quality of doctors, which is something that can’t be assessed on a daily basis. We will lend our ears to those who complain about quality of doctors. We are not fully authorised to deal with a host of issues related to medical treatment of patients, but we will do whatever we are allowed to do to deliver justice to the ones who have been unfairly treated.

Have cases of violence against doctors and acts of vandalism at hospitals gone up, of late?

I think they have increased, but not in an exponential manner. Hospitals are providing compensation to the families of patients. This quick fix is damaging the reputation of the sector. If you really think a medical team has committed mistake, then the investigation team will obviously point out those shortcomings. So, one needs to have trust in the system. We would like to educate the public not to resort to violence if they are dissatisfied with the treatment. We would like to request the public to pursue legal action rather than resorting to violence because violent activities will eventually cause damage to the healthcare sector. Violence may immediately provide some respite to people who are unhappy with the medical treatment, but it also deters good doctors from taking up serious cases. Also, the service may differ depending upon the standard of hospitals. People should consider these aspects as well. We know there are lots of deficiencies in the healthcare sector, but we must work together to bring about changes.

What is the situation of medical ethics in the country?

Medical ethics is a vast area. It ranges from being available to treat patients on time and giving 100 per cent of what you can, to being honest with patients and making yourself competent enough to treat patients. If you are not competent, it is not your fault that you couldn’t cure the patients. Someone who is diligent and puts in lots of efforts to learn new things may be competent, but doctors can also become competent if they undergo proper training. So, we need to build a foolproof system. We do hear reports about doctors falling prey to pharmaceutical companies that offer them money and junkets to push their drugs. There are also doctors who do not clearly explain to patients what can be done and what cannot. It is not ethical to take undue benefit of your position. But various factors are promoting these malpractices, which can obviously be controlled.

How can doctors maintain high ethical standard?

We need to educate, empower, enforce and enable. We know how to educate; universities know this. We are also learning how to educate people before they go to practice or before they become specialists. We can also educate them on ethics. Right now CPD programme has a threshold of 30 points. This programme will make doctors competent, but medical practitioners should also maintain high ethical standard. Our medical sector is mostly dysfunctional except in some of the urban centres. And many times doctors are held accountable for something they are not responsible for. So, we need to educate people and improve the healthcare system.

How does your appointment as chair of the council affect the multi-speciality comprehensive hospital project?

I didn’t take up other challenging jobs partly because of the need to work on the children’s hospital project. That project is absolutely necessary for the country. My appointment as chair of the medical council will probably divert some of my attention from the project, but I am totally committed to it.

Why did you feel the need for a speciality hospital?

I am a heart surgeon, but I was also trained as a paediatric heart surgeon. I was in the best paediatric cardiac centre for significant period of time. Earlier, when we started Shahid Gangalal Hospital, I was looking into a lot of paediatric cases. We also came up with lots of schemes because we were committed to handling paediatric cases. But we quickly realised that we couldn’t change much. We also noticed that fixing one organ in a child or an adult will not solve the whole problem. We need to have a systematic and comprehensive approach to child healthcare. In Nepal, all childcare services are not available under a single roof. And we only have around 1,000 or even lesser number of hospital beds for children. The number of hospital beds for children should be at least four to five times more than what is available at present. Generally, when children fall sick, they visit regional hospitals and if proper services are not available they have to come to Kathmandu. Even in Kathmandu child healthcare services are fragmented. Nepal, so far, has only concentrated on preventing infections in children by focusing on immunisation, hygiene and sanitation. We need to do more in the area of child healthcare.

How can we control anomalies in medical education sector?

The laws are becoming ineffective and the rule of law is under threat. It is a sign of systemic failure. This is why many are now retaliating. Earlier, students used to complain about exorbitant fees charged by medical institutions. Now they are retaliating. So, the first thing we need to do is to strengthen our system and ensure rule of law. The state needs to work proactively to fix these problems.

How can medical treatment be made cheaper?

We need to understand that everything costs money. But we can devise a right financing model, backed by insurance or government schemes, to keep the healthcare costs low for the public. We also should not be extravagant. There is room for improving the quality of healthcare service and reducing its cost as well.