Act on climate change to cut 'outrageous' pollution deaths: WHO

KATOWICE: Fighting climate change is one of the best ways to improve health around the world, and the benefits of fewer deaths and hospitalisations would far outweigh the costs of not acting, the World Health Organization said on Wednesday.

Keeping global warming "well below" 2 degrees Celsius (3.6F), as governments have pledged to do under the 2015 Paris Agreement, could save about a million lives a year by 2050 through reducing air pollution alone, the U.N agency said.

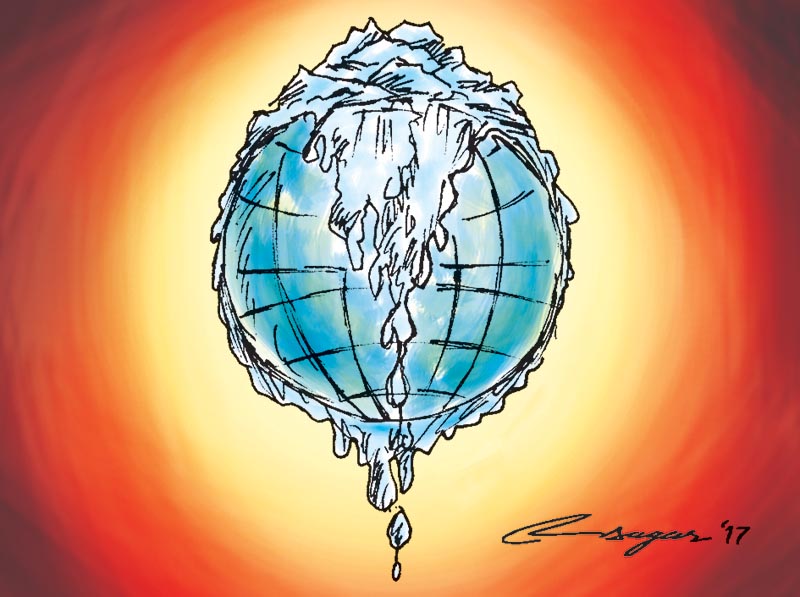

Burning fossil fuels - which emit carbon dioxide, the main culprit for climate change - is a major driver of air pollution, the WHO said in a report issued at U.N. climate talks in Poland.

Maria Neira, WHO's director for public health, said exposure to air pollution causes 7 million deaths worldwide every year.

"This is one of the most outrageous things happening today," she said. "We want to tell countries: the more you delay this (clean energy) transition, the more you will be responsible for the ... millions of deaths that are recorded every year."

Health gains resulting from action to curb climate change - from adopting renewable energy to getting people out of cars and onto bicycles - would add up to about twice the cost of rolling out those policies globally, and even more in China and India, the WHO said, citing a recent study.

WHO scientist and report author Diarmid Campbell-Lendrum said health had often been disconnected from discussions on climate change, but there was now an urgent need to break down the barriers and talk about the benefits for society.

"This is the same fight, and we have the same answers," he added.

In the 15 countries that emit the most greenhouse gases, the cost of air pollution for public health is estimated at more than 4 percent of gross domestic product, the WHO report said.

In comparison, keeping warming to the Paris deal temperature limits would require investing about 1 percent of global GDP.

Kristie Ebi, professor of global health at the University of Washington, said the world now had scientific evidence that "people today are suffering and dying from climate change".

The consequences range from chronic diseases linked to air pollution, such as asthma and lung cancer, to under-nutrition as crop yields fall and rising carbon dioxide levels in the air slash nutrients in staple foods, she added.

Inia Seruiratu, Fiji's minister of agriculture and disaster management, said his Pacific island nation was already experiencing the effects of climate change on health, such as an increase in water-borne diseases after storms and floods.

It is working to build solar-powered health clinics that can also withstand strong winds and other extreme weather, he noted.

SEE YOU IN COURT?

Despite such efforts, the WHO report said financial support - particularly for small island nations and the poorest countries - remains "woefully inadequate".

Only about 0.5 percent of funds provided by international institutions for measures to adapt to climate change have been allocated to health projects, it added.

Money is also lacking for scientific research into the different options for tackling the problem, Ebi said.

If countries do not ramp up efforts to protect their people's health on a warming planet, the battle is likely to end up in the courts, warned WHO's Neira.

That is already happening, lawyers and plaintiffs in climate change legal cases told reporters on the sidelines of the Dec. 2-14 talks in the Polish coal-mining city of Katowice.

In Switzerland, for example, a lawsuit has been filed on behalf of about 1,000 elderly women who are challenging the government's emissions reduction policy on the grounds that they are vulnerable to heatwaves exacerbated by climate change.

And in an ongoing court case filed against the U.S. government, health experts have diagnosed plaintiffs with asthma linked to air pollution and emotional trauma caused by climate stresses, group member Vic Barrett, 19, said in Poland.

"It is not just about saving the planet and the glaciers in the future - it is about protecting the health of the people right now," said WHO's Neira.