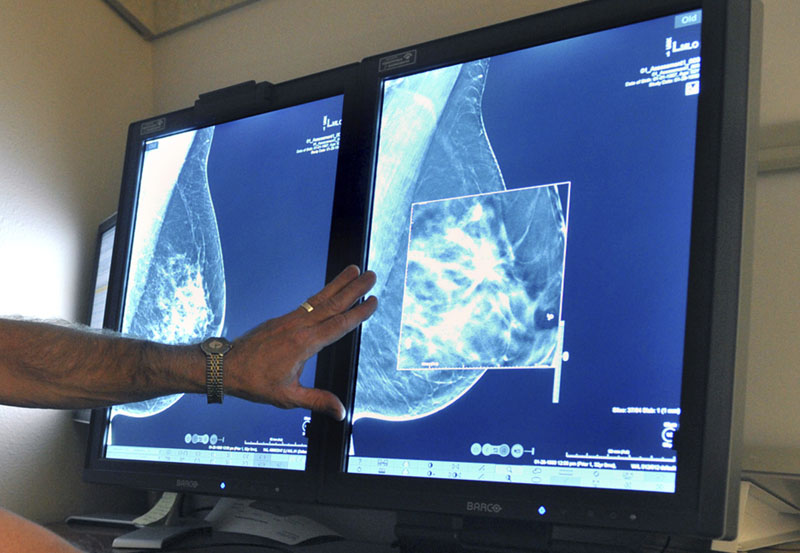

MRIs of dense breasts find more cancer but also false alarms

Giving women with very dense breasts an MRI scan in addition to a mammogram led to fewer missed cancers but also to a lot of false alarms and treatments that might not have been needed, a large study found.

The results give a clearer picture of the tradeoffs involved in such testing, but they can't answer the biggest question — whether it saves lives.

For women with dense breasts trying to decide on screening, "the dilemma remains," Dr Dan Longo of the New England Journal of Medicine wrote in an editorial published with the study on Wednesday.

About half of women over 40 have dense breasts and about 10% have very dense ones. That raises their risk of developing cancer and makes it harder to spot on mammograms if they do. US regulators are making rules to require that women get breast density information when they have mammograms, and many places provide it now. But what to do if you have dense breasts is unclear — it's not known if more or different types of screening such as MRIs or ultrasounds help.

The study involved more than 40,000 Dutch women ages 50 to 75 with very dense breasts who had normal results from a mammogram, a screening X-ray offered every two years in the Netherlands. About 8,000 of them also were offered an MRI scan, which uses powerful magnets to create detailed images, and 4,783 women agreed.

Researchers then tracked how many breast cancers were detected in each group within two years. Finding more of these "interval cancers" implies that the initial screening may have missed them.

The rate of these cancers after two years was twice as high in the group that was only offered mammograms. This suggests that adding MRIs to initial screening did catch more cancers, but they also gave a lot of false alarms— about 80 per 1,000 scans. Three-quarters of women who had a biopsy after a questionable MRI turned out not to have cancer.

MRIs also led to more side effects during the scan or later testing, such as fainting or problems from an IV. And they cost much more than mammograms.

The study only looked at the first two years of screening with MRIs and it's too soon to say whether the test will save lives.

Without such evidence, it's tough to say what value there is in finding more cancers, especially many very small, early-stage ones, Longo wrote. Doctors already know that some of these will never cause symptoms or become life-threatening.

"Our dilemma is that, for most tumours, we cannot tell the difference between cancers that can kill you and those that cannot," he wrote.