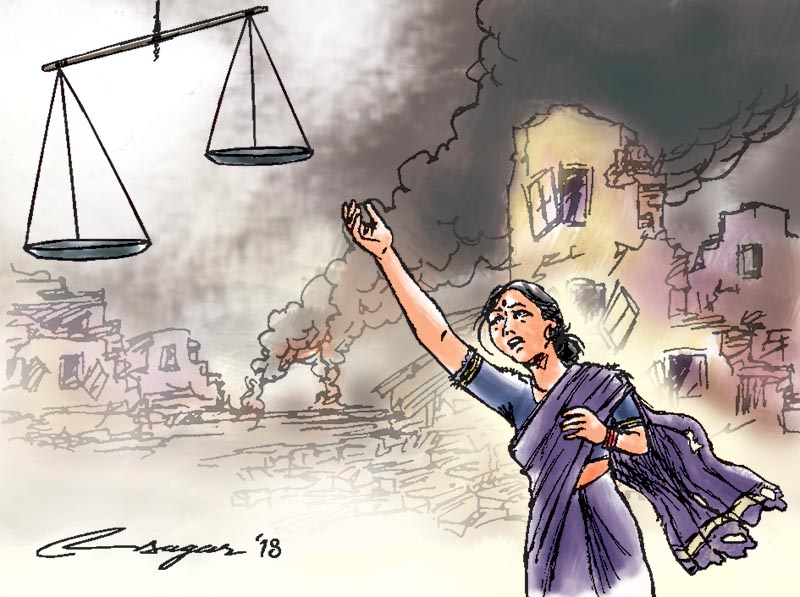

Conflict-affected women: No end to their sufferings yet

As we mark the 12th anniversary of the historic peace deal that ended the decade-long armed conflict, we must take it also as a reminder of the fact that the state has largely failed to address the sufferings and need of women affected by the war

Today we mark the 12th anniversary of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement, which formally ended the decade-long armed struggle launched by then Maoist rebels. The 1996-2006 civil war claimed nearly 16,000 lives and displaced around 1,300 people. The last 12 years, however, have gone without tangible progress when it comes to delivering justice to conflict victims.

The plight of conflict-affected still remains the same. There is very limited space for women where they can openly share their sufferings. Nor has there been any substantial work to address the multiple needs of conflict-affected women.

On political front we have seen a sea change though — the country has abolished monarchy, we have adopted a new constitution, we held three tiers of elections last year and adopted federal governance system and we are now in the process of implementing the constitution and strengthening federalism. Political parties have largely been busy in the last 12 years to achieve the above-mentioned. But the political leadership has done precious little to deliver justice to conflict-affected women.

Many women who lost their husbands to the bloody war or who faced sexual violence at the hands of the state forces, as well as members of the rebel party or who were displaced from their homes or whose family members who, were disappeared during the conflict are still awaiting justice. Conflict-affected women continue to suffer from familial, social and political injustices in their daily lives.

There have been a lot of talks about what we call transitional justice, but immediately after the peace accord, our political actors, it seems, lost the plot. Initiatives for community reconciliation should have started right after the peace deal back in 2006. Nor has the state done anything substantial to make the communities, which were not affected by the war, aware of the sufferings of the conflict-affected many women. Nor the communities were made aware of how they could have contributed to establishing the identity and dignity of the conflict-affected women.

With the promulgation of the constitution in 2015 and elections last year in the spirit of the new charter, there have been claims that the country has now capped the long-drawn transition and concluded the peace process. But what the state and political leadership are forgetting is justice to conflict-hit people is a major component of the peace process, and unless that is ensured, it will be wrong to conclude that peace process has been concluded.

Conflict-hit women are still struggling to sustain their daily lives. They lack financial and social security — they are still unable to pay hospital bills, they are facing a tough time paying for their children’s education and their struggle to deal with psychological issues is immense.

Women who were 18-22 years of age when they bore the brunt of the conflict are now 38-40 years old. Those who were born when the armed conflict was at its peak are now 20-22 years of age. Those mothers who lost their husbands to the war earlier were more focused on raising their children. Now they realise that they too have their own needs, financial and social, especially after their grown-up children started leaving them. This fact I learned during a recently held workshop for conflict-affected women.

However, the state and non-state structures have not been able to address such specific needs of conflict-affected women. The children who have now grown up to understand the sufferings of their mothers have developed the notion of victimhood, which could contribute to instilling negativity and a sense of hatred towards a certain section in them. Nepal is a signatory to CEDAW which talks about eliminating all form of discrimination against women and has formulated a national action plan for the protection of women. Nepal has also committed to addressing the structural issues of the conflict. But these conflict-affected women are still suffering from many forms of discrimination and facing violence on a daily basis.

“Our bodies have become frail. We don’t have hope for the future.” “I can’t sit straight even for half an hour because of the pain of torture inflicted on me during the time of war.” “What we faced was like a storm which we were not prepared for, and this has left us with huge scars which will remain with us until our death”. These are some personal accounts of conflict-affected women I have come across.

Yes, the government has formed two commissions to ensure justice for the conflict-hit. But they came into being almost after nine years of the peace deal. In the last three years, the only major work they have performed is a collection of complaints. But conflict-affected women say they have no hopes from the two commissions. The conflict-affected women say the two commissions have failed to take the issues up with the state level and provide various levels justice in the last three years.

Now in today’s changed political landscape of the country, it is also the responsibility of local and provincial governments as well as non-state structures that are active in the field of peace-building to take initiatives and come up with comprehensive package programmes to address the sufferings and needs of conflict-affected women.

Risal is chief executive officer of Nagarik Aawaz