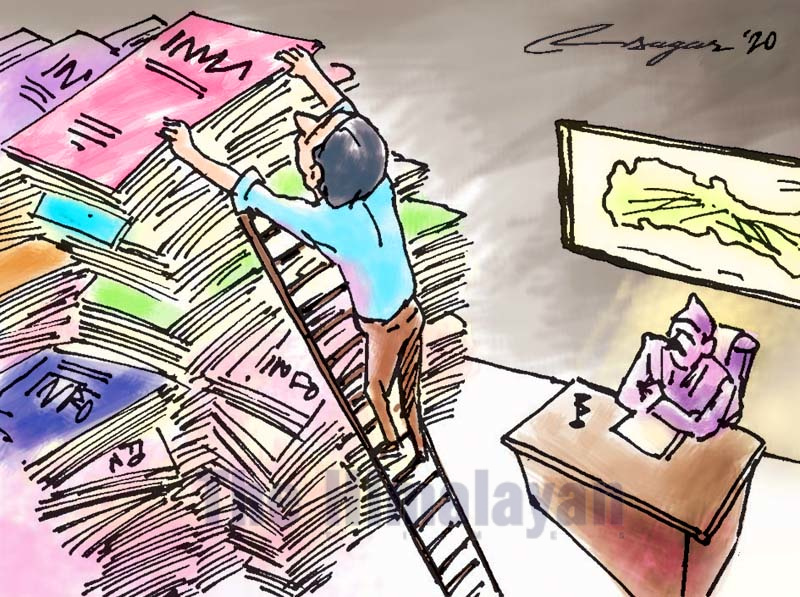

Frail local governance: Old administration ways to blame

The dismal state of local governments can be partly attributed to the restructuring exercise of the bureaucratic apparatus after the 2017 local level election, which failed to see the heterogeneous socio-economic needs of local polities

Three years after their inception, local governments are struggling to navigate their way around legal intricacies, build institutional strategy and maintain bilateral accountability, where the linkage extends not only to the orders of the governments but also to the public. Constitutional provisions and other statutory arrangements have accredited local governments with executive and legislative autonomy, a theoretical underpinning of great essence to the existence of such a polity close to the people. But the way local institutions have gone around conducting their business signals a departure from the tenets of public accountability and efficient governance.

The Office of the Auditor General (OAG), in its annual report for FY 2018/19, makes several cases with regard to the state of frail governance, lack of due diligence and gaps in the capacity of local governments to carry out their mandate.

The Local Government Operations Act 2017 in Sections 71 and 73 entrenches conditions on the formulation of the budget, approval from the local executive and devolution of authority to exercise budgetary control.

The OAG notes that 105 local governments failed to comply with this arrangement.

Similarly, under Section 17 of the Inter-governmental Fiscal Arrangement Act, local governments are required to prepare a Midterm Expenditure Framework (MTEF), a practice that has almost been non-existent among the third-tier government. According to the same report, 386 local governments did not conduct internal audits, 418 did not use the mandated audit framework and 10 failed to present their records for the final audit.

Concerning the financial discipline of the local governments, the OAG has made observations on expenditure arrears, shortfalls in complying with the Public Procurement Act provisions, shortcomings on matters relating to inter-head budgetary transfers and operation of non-allocative funds. Of late, local governments have accumulated arrears of Rs. 38 billion. It has also expressed concerns over the failure of the local government to monitor development projects effectively, reeling exuberant overhead costs and compromising settlement standards of advance clearance post-internal audit.

The buck doesn’t stop at the local level. The dismal state of local governments can be partly attributed to the restructuring exercise of the bureaucratic apparatus after the 2017 local level election. The process failed to acknowledge the heterogeneous socio-economic needs of local polities, to such an extent that the current administrative set-up is reminiscent of an archaic unitary configuration that pays no heed to innovation, adaptability and end-user orientation.

While the old ways of administration prevail, under the federal structure, the local governments are eligible for revenue generation and to receive funds (this includes receipts from the revenue sharing arrangements and grants) from both state and federal governments.

One can only question whether the local units can handle all these responsibilities with the current blueprint of administrative institutions.

Inherently, this had led to issues of incompatibility with far-reaching implications for good governance and efficient public service delivery. For instance, local governments bear an extra burden of reporting to several ministries, in-line agencies at the state and federal level, constitutional commissions like the National Natural Resources and Fiscal Commission (NNRFC) and the National planning Commission (NPC), and the Auditor-General to name a few.

Add to this, the state of infrastructure, lack of competent human resources and several entities at the state and federal level trying to get the local governments to report to them in a format whatsoever pleases their interest.

Even with all these concerns addressed, the question of bottom-up accountability linkage that a local government must fulfill lingers.

While the current Right to Information Act lays the bare minimum to specify the scope of revenue/expenditure and financial transactions that one can demand from the local governments, it is still better than nothing. Other pieces of legislation do fill in the gap. The Local Government Operations Act makes it mandatory to make its financial reports public within seven days of the end of every month.

However, this only adds to the woes of the administration.

A better approach would be to streamline all financial reportings, forecasts and analytics into one robust information system.

The Public Expenditure and Financial Accountability (PEFA) secretariat under the Ministry of Finance (MoF) has already piloted the Sub-National Treasury Regulatory Application (SuTRA), a web-based platform that facilitates structured financial management.

But its applicability is limited to end-users; in this case the NNRFC, MoF and the NPC.

Considering the cost and effort already being put into the formulation of SuTRA, it can be further enhanced to accommodate other subcomponents, that is, reporting of consolidated funds, treasury position, the summary status of grant utilisation and other projection components.

The features of an improved system extend beyond mandatory reporting to front end access for the taxpayers about the financial status of each local government in real-time.

Jha is researcher at Samriddhi Foundation, a research and educational public policy institute