No politics and good voters: Case for local development

The upper mountain eco-system is characterised by mono-ethnicity, mono-culture and mono-religion, and the people there are bound by a single faith. Therefore, the voters of this area mostly decide on a ‘single’ candidate

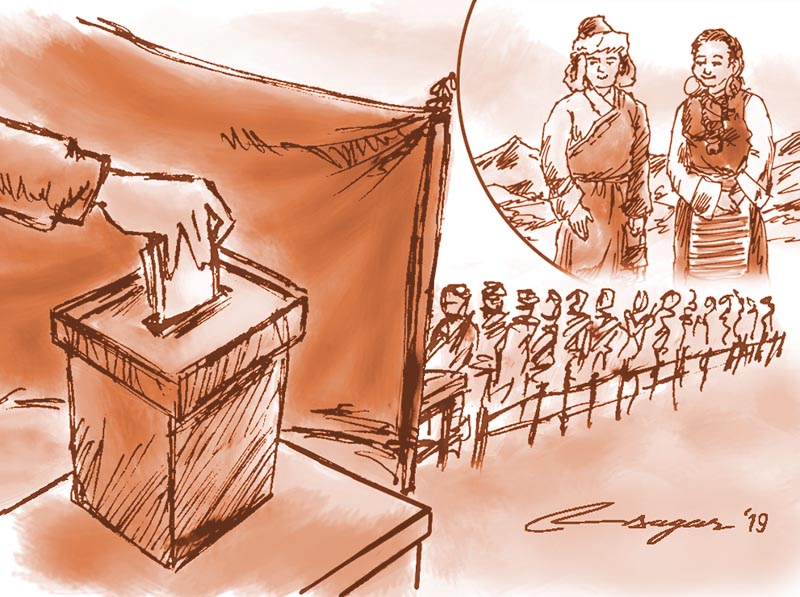

Politics for development is common political parlance. However, for the people (voters), their only concern is development. Most voters in the mountain region of western Nepal vote not for politics, but for development. The same voters cast their votes for different party nominees based on the lofty development promises made to them by the candidates. This was seen in Humla district in Mid-west Nepal during the last three-tier elections at the local, provincial and federal levels. The voters of Namkha-6 Rural Municipality openly asserted that they voted and would do so only for their local development. This indeed is a good practice for local development.

Since the partyless Panchayat period, I’ve closely observed the parliamentary elections - Rastriya Panchayat, multi-party polls, Constituent Assembly and Federal Parliamentary polls - plus local level and province level elections. MPs of the Rastriya Panchayat, especially from Manang, Mustang, Dolpa and Humla districts, used to be elected or selected from among those who had no political alliance with the multiparty system. There is almost a similar legacy or practice, both post-restoration of multiparty system (1990) and even today in the republic set up (2006).

The reason behind this could either be the low level of awareness about multiparty system, or politics, or elections for the people there are solely for development, or both. Elections for the people are considered a necessary evil, so why not select the best from among the best available in the poll arena?

MP Chhaka Bahadur Lama won the general election of 2017 from Humla as an independent candidate. He used to represent Humla under different political hats. From the same district, Jivan Bahadur Shahi, a National Congress candidate, became the province MP and is the opposition leader of Karnali provincial assembly. They won because the voters saw that local development was feasible only from these two personalities.

Humla is the northwest district of western Nepal, which has only seven rural municipalities. It is the second largest of the country’s 77 districts and borders Tibet to the north, Mugu to the east, and Bajhang and Bajura to the south and west, respectively. As of today, it is reachable only by foot or small aircraft from Nepalgunj and Surkhet. But a motorable road from Hilsa (Tibet border) to the district headquarters of Simikot is open for jeep services.

Likewise, construction of a motorable road from Jite Gadh Bazar on the Karnali Highway, at the confluence of the Tila and Karnali rivers, to Simikot, is almost half open and likely to be completed within a few years. There are two roads that have opened from China - one from Hilsa and the other from Lapche. Both roads reach Simikot. Both the roads are the results of the efforts made by MPs Jivan Bahadur Shahi and Chhaka Lama. The locals understand this.

Humla is the gateway to sacred Kailash-Mansarovar in Tibet, China, where on average 12,000 Indian tourists per year visit from Nepal from June to October.

From the tourist point of view, the district is an ideal destination. The Limi Valley (once a forbidden area); the sacred Karnali River flowing from Tibet, China via Nepal to India; Saipal, Nalakakar, Gorakh and Chandi, Changla and Yenrega Himals; Jhongdik (Thaksi) Limi, Lama Kholsi and Kermi hot water springs; buckwheat-based honey, amazing Chyathara waterfall, and Kharpunath and Shiva temples.

All local governance systems are superseded by the Gumba system, the very original Tibetan culture of the area. Namkha Rural Municipality feels like a walk back in time to the medieval period. No local governance goes beyond the cultural and religious faiths of the Limi Valley. All are united under the Gumba management and preserved original Tibetan culture.

The command issued by the Ward-6 chairman of the rural municipality is the decree, and he is strong and assertive in the management of local affairs of their community across the ward or the whole rural municipality. Hence, the election results turn up according to the wisdom of the charismatic leadership of the priest, or the mukhiya, or whatever it has been called by in the new constitution (2015). The legacy of the Patriarch, like that of the medieval church system, is somehow prevalent in local governance.

The upper mountain eco-system is characterised by mono-caste/ ethnicity, mono-culture and mono-religion, and the people there are bound by a single faith. Therefore, the voters of this area mostly decide on a ‘single’ candidate on the eve of the elections for a single development agenda/ issue or interest.

By and large, Nepali politics, especially in the remote and mountain areas, is in the primitive stage. All possible practices of political systems have been introduced over the last several decades. However, a democratic system has yet to be institutionalised. The people, or voters, only see the elections as a means of choosing the best and dearest development partner or leader.

The pace of political development is very slow, and the ecology of the region is different. Most Humlis are good voters and quite serious about their needs. They have their own social system, which governs the local affairs or the state mechanisms. A good voter always looks for immediate development rather than anything else.