Protecting the Economically Vulnerable Population

Kathmandu, July 7

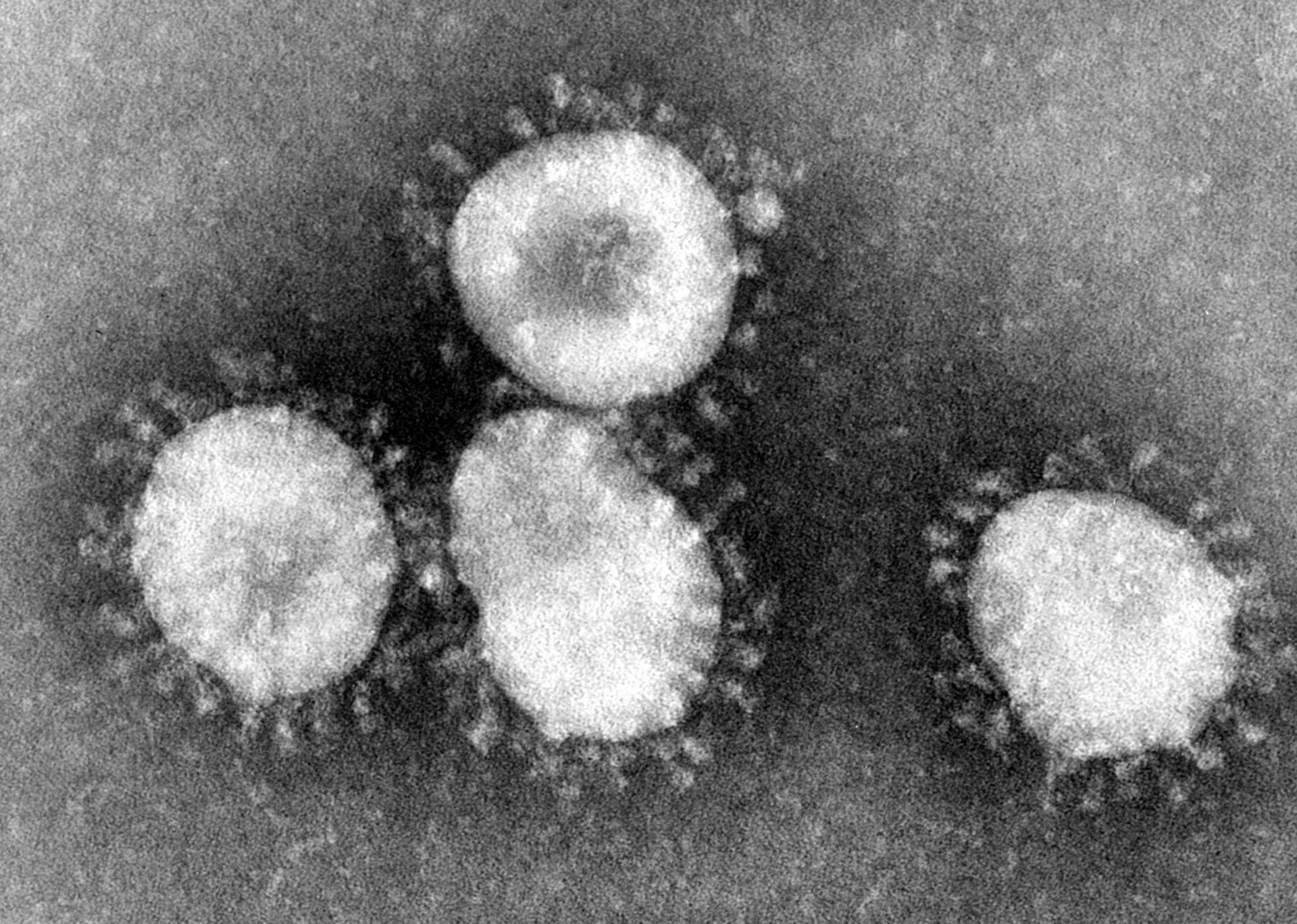

What started as a health crisis in the form of the COVID-19 pandemic has now unfolded into a global economic and livelihood crisis. While the ubiquitous quarantines and lockdowns may have saved many lives and provided an additional benefit of environmental improvement, their enormous consequences on people’s livelihoods are conspicuous.

In Nepal, for example, a recently conducted Rapid Assessment of Socio-Economic Impact of COVID-19 in Nepal by the Institute for Integrated Development Studies (IIDS) indicates that 28% of men and 41% of women lost their jobs following the lockdown. Furthermore, the impact is concentrated among the income-based vulnerable population that already sustain their lives with direly scarce economic resources. The ongoing pandemic-led livelihoods crisis, if persistent, is not only likely to have further sizable impacts on the already vulnerable population but could also throw more people into poverty traps.

In Nepal, one-fourth of the population lives below the national poverty line (i.e. live on less than $0.5 per day). Given their finite earnings and scarce resources, how they sustain their lives and grapple with various socio-economic constraints is a pertinent topic of discussions concerning poverty.

Typically, income-based vulnerable people are more likely to face food insecurity and have limited access to health care facilities. These challenges are potent, especially considering that they also tendto engage in physically demanding work.

Food insecurity is a long-standing issue in Nepal.

According to the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS), as many as 52% of Nepali households area food insecure, and food insecurity is pronounced amongst households in the lower wealth quintiles.

The 2019 Nobel Prize-winning economists Esther Duflo and Abhijit Banarjee, building on the work of another Nobel Laureate Angus Deaton, have noted that food insecurity amongst the impoverished population is concerning given the fact that they spend a significant amount of their earnings, roughly one-half to three-fourth of their total income, to purchase food.

Following the COVID-19 lockdown in Nepal, a large proportion of the economically vulnerable population have lost their jobs and incomes, and have therefore become more susceptible to food insecurity. This quandary has severe implications on the human capital depreciation of the country, which in turn threatens to derail the national economic growth.

While the physical toil and economic hardship of the economically vulnerable population garner much public attention, their psychological states under resource scarcity and poverty often go unnoticed. Behavioral economists Sendhil Mullainathan and Eldar Shafir have found that poor

farmers have significantly higher cognitive ability post-crop harvest as compared to pre-harvest,

suggesting that economically vulnerable people are easily psychologically distracted under resource scarcity.

Furthermore, scarcity-led psychological distractions could lead them to make adverse economic decisions, such as falling into huge debt traps, which further aggravates their economic hardship.

So, while it is important to understand the economic struggles of the poor population, which is likely to exacerbate further in the immediate future, it is equally crucial to recognize the interplay of the socio-economical and psychological factors, especially at a time when the suicide rates are noticeably high.

The role of government becomes crucial in recognizing the challenges and needs of its citizens.

However, the current crisis has gravely questioned the government's responsiveness, as evidently reflected in its dire preparedness for health emergencies, resource allocation, and mobilization, giving rise to what has now developed in a nation-wide public protest. Post the pandemic crisis, thousands of migrant workers have returned to Nepal and more are due to return.

Given the fact that many of the returned migrants will find themselves with no immediate job security, the government is faced with the urgent challenge of overseeing their safe return and accommodating them. However, the incompetent management of the government thus far has also raised serious concerns over its credibility.

Amidst these uncertain circumstances, the question of how the government should move forward to address the needs of its citizens, especially the economically vulnerable population, becomes a monumental one. Job security is an utmost priority to keep the economy afloat. With several big infrastructure projects in sight, the government can employ a large number of local workers in those projects with adequate safety measures. We have to scale-up and improve our quarantine and health care facilities to accommodate the increasing number of virus-contaminated individuals, possible suspects, and returned migrants. The government can also utilize the local workforce in those facilities with adequate safety measures. While the recently announced budget does not guarantee outright economic protection for the vulnerable population, the tax benefits for small and medium-sized enterprises may help in their economic recovery. Therefore, the

government should ensure the smooth running of those enterprises. The role of provincial and local governments is equally crucial in engaging and incentivizing its local workforce. The immediate priority could be incentivizing agricultural production, which is already underway in several municipalities. A case in point is the rural municipality of Miklajung of Panchthar, which has announced an incentive of 1 lakh prizes for farmers producing more than 40 muris of paddy this year. More of such economic incentives are required at the municipal level to engage the local workforce and increase agricultural production and food security. Lastly, it’s about time that the government cuts down any extravagant spending in all three tiers and focuses on the more urgent issues at hand.

Niraj Khatiwada is a Ph.D. candidate in Economics at the University of New Mexico, USA

Sudhigya Pant is a fresh Juris Doctor Graduate from University of Sydney, Australia