Rajbiraj at risk: Misplanning Nepal’s oldest planned town

The vision, values and goals of urban planning and highway alignments in this new century demand a paradigm shift from the traditional mode of town-planning, which is to say an altogether new strategy that incorporates the principles of deep ecology

If a planner in or out of his mind comes out with a plan to drive in a 50-metre highway through the very heart of Kathmandu’s capital in the name of development, what kind of pandemonium could it set off among the valley populace and the hue and cry it might bring? Most would dismiss it as just wild fantasy or plain daredevilry.

A similar hoax that is hardly less macabre failed to raise eyebrows recently among the designers of highways and decision-makers in Nepal’s south-east in Saptari when a coterie of self-declared developmentalists tried to impose their design on the oldest township planned in Rajbiraj.

The public there were not informed on what was about to happen, leave alone the larger issues at stake. Neither the government nor the civil society was coming forth on the agenda: secrecy was serving the conspirators’ interests better, not transparency nor the information that was the citizens’ inalienable right on what was going to matter for them. The only information made available was a dire warning to leave and move away.

No assurance for settlement, no compensation.

Appeals against the encroachment proved a cry in the wilderness.

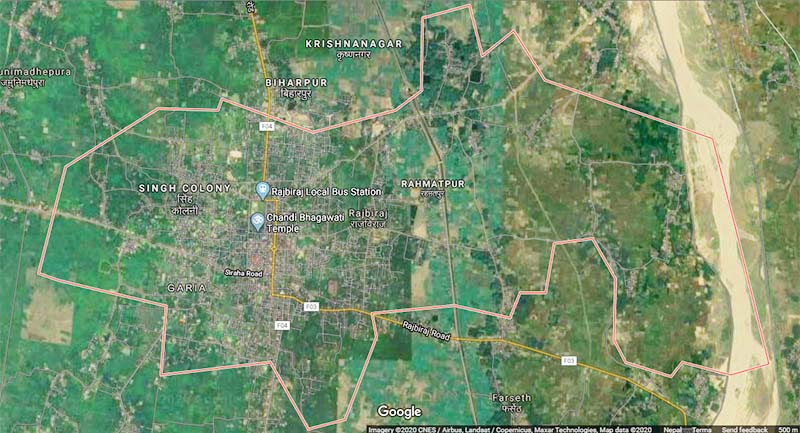

Rajbiraj happens to be the town planned as a miniature Jaipur, the Pink City of Rajasthan in India. It emerged in the course of rehabilitating Hanumannagar, the district headquarters of Saptari, which was flooded by the River Koshi.It was in the news first in the early Forties when Jay Prakash Narayan and Dr. Ram Manohar Lohiya, fugitives from Hazaribag Jail and imprisoned in Hanumannagar jail, were set free by the rebels.

Heavy floods in the late Thirties had forced the residents to settle 12 kilometres west, and the urban structures, including the ancient shrines and other cultural assets, were shifted.

Declared a municipality in 1960, this eight-decadeold town was now facing a dire threat from ‘planners’ bent upon driving a highway right through the core of the town, which would not only raze hundreds of households there, but would also uproot, displace and drive away families who had been born, had grown up and lived there for generations.

If the perpetrators were least mindful of the collateral damage the decision would bring to the heritage value of the town, to the air, to the peace and the tranquility of the township when traffic would grow, one could hardly imagine a more dastardly project.

Development, after everything said or done under its pious promises and proclamations, stands only a hair’s breadth away from destruction. Ignorance, the saying goes, is bliss and silence golden. Ignorance of the would-be victims of Rajbiraj was, instead, turning into bane, and their desperate silence the development-mongers were sharpening into a murderous tool in their frantic bid for the loot the framers of this fraudulent scheme had in mind.

The funnier part of the game was that quite a few of the local administrators, hand in glove with some of the leaders, would not flinch from becoming the greatest fraudsters in the history of the district. This is what the two scribes of this write-up discovered, rather late when one of them was in town on a short visit there and was met by a group of six anxious citizens who told him what was cooking. Yet it was still not too late.

Consultation then followed on the crisis with a wide range of resource persons, consultants, advocates, jurists, administrators, architects and town designers for months in Kathmandu, with teams shuttling between Rajbiraj and the capital for quite awhile. And efforts to move ahead against the sinister agenda concluded in a decision to file a case in the Supreme Court for a writ to stay the demolition. This, fortunately, worked.

The two-some, in fact, failed to find a single soul among the dozen distinguished persons consulted who would go with the malicious plan to destroy the townscape instead of opting for a far more creative and far less costly option of ring-roading Rajbiraj. One of them, the planner of a township in western Nepal, could not help marveling at the excellent design and grid-plan of Rajbiraj, and graciously offered to do what he could to help. Patience and perseverance were beginning to pay.

Villagers living around and kilometres beyond the 40-hectare span of the town would be more than happy to share their space at much less a price than the exorbitant cost compensation would call from the government if it sees reason to pay the price for divesting the lands and property of the displaced.

On compensation, however, the state is silent.

The vision, values and goals of urban planning and highway alignments in this new century demand a paradigm shift from the traditional mode of town-planning, which is to say an altogether new strategy that incorporates the principles of deep ecology.

It has to be holistic, inclusive, inter-disciplinary, futuristic, as also resilient and participatory as well as sensitive, not just to the shortor mid-term needs of the inhabitants, but also to their long-term prerequisites.

Given the heritage that the district represents and keeping in mind the strategic value of its location in the Saptakoshi corridor nestled between the frontline of the Himalayan belt, south of the Tibetan plateau, and the heartland of Northern Bihar in India, given moreover the symmetry of the north-south and east-west frame of the future township, the idea of developing a mega-town in this region may not remain a mere dream for long. The myopia of the hastily drawn highway alignment disallows any such scope.

It, in fact, may foredoom the whole dream. The earlier that misstep is prevented, through the court writ, political sanction or public protest, the better.