Responsibility to protect

We recently completed a three-year research project that takes stock of the last decade’s debates about prevention and intervention, sovereignty and responsibility, selectivity and hypocrisy

Ten years ago, world leaders agreed that the international community had a “responsibility to protect” populations from genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and ethnic cleansing. A decade later, the world’s record in fulfilling the Responsibility to Protect (R2P) remains poor, with hundreds of thousands of people in Iraq, Syria, Myanmar, Sudan, South Sudan, the Central African Republic, Burundi, Nigeria, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo still threatened by mass atrocities. If R2P is to work for them, we must dispel some widespread myths and focus our energies on the practical challenges of protection.

As it stands, many pundits see little promise for R2P, foreseeing instead an intensifying deadlock between Western interventionists and non-Western stalwarts of sovereignty. Many find only reason for despair in the global rise of powers like China and India, whose elites were socialized in opposition to the Western-led order from which R2P emerged. Those countries’ resistance to intervention, says Harvard’s Michael Ignatieff, “will become increasingly influential.” But is sovereignty really what emerging powers are defending? And does effective protection of populations always come down to intervention?

We recently completed a three-year research project that takes stock of the last decade’s debates about prevention and intervention, sovereignty and responsibility, selectivity and hypocrisy. We found that the widespread view that the conflict is between “the West,” promoting intervention, and “the rest,” defending sovereignty, is misleading in two critical ways.

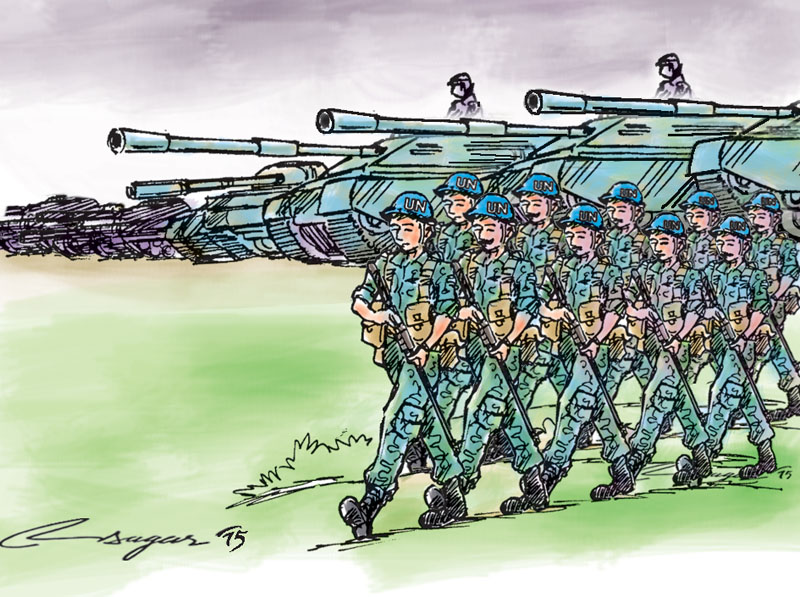

First, “the West” is hardly keen to intervene, diplomatically or militarily, to protect populations from mass atrocities. The British parliament voted not to intervene in Syria; Western countries are among the smallest contributors to United Nations peacekeeping operations.

It is equally wrong to paint “the rest” as callously defending the principle of sovereignty in the face of human suffering. This depiction is offensive to the thousands of UN peacekeepers from South Asia, Africa, and Latin America who have helped to protect civilians. Consider the South African and Tanzanian troops using military force, under a Brazilian commander, to fight armed groups in the Congo, and the many African statesmen whose efforts have been central in mediation attempts across the continent. China, often hesitant about political and military intervention, is playing an increasingly important role in the peace negotiations in South Sudan.

Second, global support for protection from mass atrocities is far from dead. True, NATO’s abuse of the UN Security Council mandate for regime change in Libya poisoned the atmosphere, and Russia’s cynical rhetorical appropriation of the language of protection in Georgia and Ukraine added fuel to the geopolitical fire that has tragically blocked meaningful action to protect people in Syria.

But the Security Council did agree to intervene in Libya, and it sanctioned intervention by a French/African Union force to prevent genocide in the Central African Republic. This reflects a significant shift from the 1990s, when the international community stood idly by as genocide was carried out in Rwanda and Srebrenica. Today, when there is overlap with other strategic interests, and broader geopolitical considerations do not stand in the way, states are far more willing to act, particularly against non-state actors like the Islamic State, Boko Haram, or Congolese rebels.

Unfortunately, even in these cases, the world does not have enough to show for its efforts. To protect populations more effectively from mass-atrocity crimes, governments, international organizations, and civil-society groups should focus on practical challenges and learn from past mistakes.

Two imperatives stand out. First, there is a need for constructive debate about how the Security Council manages the exercise of military force. After the regime change in Libya, it is unlikely that world powers will again give carte blanche to humanitarian military intervention by third parties. Reform proposals from the Brazilian government and Ruan Zongze, a leading Chinese thinker, provide good starting points for this discussion.

Second, policymakers, academics, and activists around the world need to address the question of how to protect effectively. All of our tools – sanctions, UN peacekeeping, military operations – have mixed records. Protecting people from mass-atrocity crimes will always be about assessing the risks and identifying the lesser of several evils in a particular situation. That said, all of us can take a more critical look at our preferred strategies and blind spots.

One way of doing so would be to stop preaching at one another, and instead engage in constructive and open-minded discussions. India and many other countries could share their decades of experience in UN peacekeeping with Europe and the US.

Neither of these suggestions requires unrealistic breakthroughs in highly charged geopolitical stand-offs. Instead, they demand humility and open-mindedness on the part of policymakers everywhere.

Brockmeier is a research associate at the Global Public Policy Institute in Berlin. Rotmann is Associate Director at the Global Public Policy Institute in Berlin.

© Project Syndicate, 2015. www.project-syndicate.org