Sustainable conservation: Possible only when the locals benefit

It has been substantiated that poor people bear the brunt of conserving the protected areas while the rich - mostly outsiders enjoy the greater share of the benefits. This will only widen the rift between them

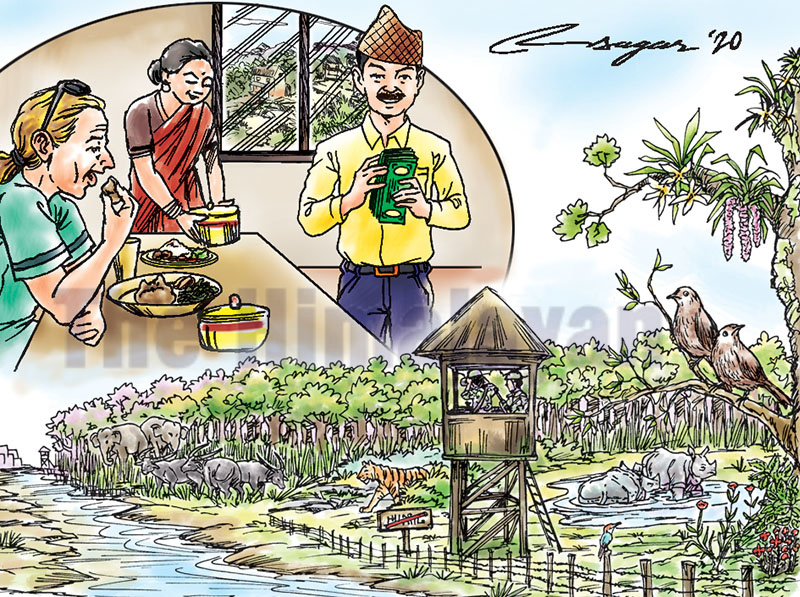

Nepal is doing exceptionally well in biodiversity conservation, which has been globally lauded. Now, some outsiders, wealthy and influential, are scrounging to take advantage of it. The government has drafted a new provision in a bid to encourage a range of commercial tourism activities in the core and buffer zone of the Protected Areas (PAs) of the country.

This move is aimed at augmenting the Visit Nepal 2020 tourist arrivals. However, there is a rallying call regarding the negative impact the proposed provision will have on biodiversity and, in particular, to the wildlife thriving in these protected areas. Taking into account the conservation experts’ view, evidence generated by researches and previous experience of other countries, the cry of the conservationists is well-founded.

Consider that these activities are established and run within the environmental limits. If this situation exists, the conservationist might also give a green signal, and it will be a source of lofty revenue for the government, high income for the owners and job opportunities for the most affected poor local people through conservation. What more could you ask from these tourism activities? It’s a neat win-win win approach for all.

But there is yet another story of paramount importance, which is neglected - about the share of benefits from tourism activities the local people living there for decades are getting. Don’t these stories deserve to be heard? Or is expecting the locals to get a fair share of the tourism benefits a more-than-realistic target? Legitimately and rationally, the answer should have been a clear “No.” But things always do not work out that way. These are critical yet fundamental issues that should have received prominence in policy and implementation.

The local inhabitants that live in the vicinity of the PAs are dominantly poor. The relation between the protected areas and poverty is a long-standing debate in academic and policy circles.

However, it has also been richly substantiated that poor people bear the brunt of conserving the PAs while the rich - mostly outsidersenjoy the greater share of the benefits.

And this very move will be a factor widening the rift between these two categories of people.

Proponents of the provision might put forward the logic that once these activities begin operating, they will also benefit the local communities significantly. Superficially, it seems the right reasoning and intention. But when we delve deeper into the matter, won’t it be plausible to say that the claim they are parroting is obstructing justice to the local people? Or implicit biases cloaked in the form of opportunity? The locals should be the owner of the opportunities if they exist.

Or is there legitimacy in treating the poor people always as subservient? People who are the stewards of our much-hailed conservation and must face the brutal cost of it are being compensated by scanty menial and low-paying jobs. What is even more crucial is, who will guarantee that the people and product use will be more local? This case epitomises the

case of allowing access to people from outside but excluding myriads of diverse indigenous people and local people. This could lead to not only rancorous public disagreements but also resentment to conserve the biodiversity of those wild places.

The handful of outside and opulent people take away the dominant pie of the benefits, a few natives get minimal benefits while the majority of the natives shoulder the cost of conserving a global public good. Isn’t this outright discrimination? It is an alliance of corporate capital and policymakers, and marginalising the poor people - the perfect working of capitalism at the micro-level.

A more justifiable, empowering and leadership role has to be handed over to the local people, the poor in particular. Doable actions are critical to stop the agitation for the dismantling of the protected areas and also to avoid those conservation interventions that cause more harm to those people. All these will ensure the sustained success of conservation. Interventions include capacity building of local communities, as they need guidance and technical assistance in setting up commercial arrangements, a conducive environment for high-spending tourists to enjoy in their homestay or similar accommodations, and developing the right kind of tourism infrastructure, among others.

In essence, the locals should take the lead role while providing these sorts of services and facilities to the visitors so that they can reap not just as much as they possibly can, but also generate a comparable amount of revenue if these activities are operated by opulent outsiders.

Also, these kinds of activities are likely to be more conservation-friendly and, more importantly, a large share of the revenue generated would be channeled back for conservation purpose and to the communities. When the benefits of tourism flow primarily to the local communities, they will value the protected parks more. Thus, this will be a more sustainable and purposeful strategy.

If we take the view that the typical opportunities and arrangements offered through tourism activities, which has become a well-established tradition, are good enough, especially for the poor local people, then it’s time to talk about the lopsided perspective.

Shahi is research assistant at University of Georgia, USA