The budget blues: Nepal’s poor spending capacity

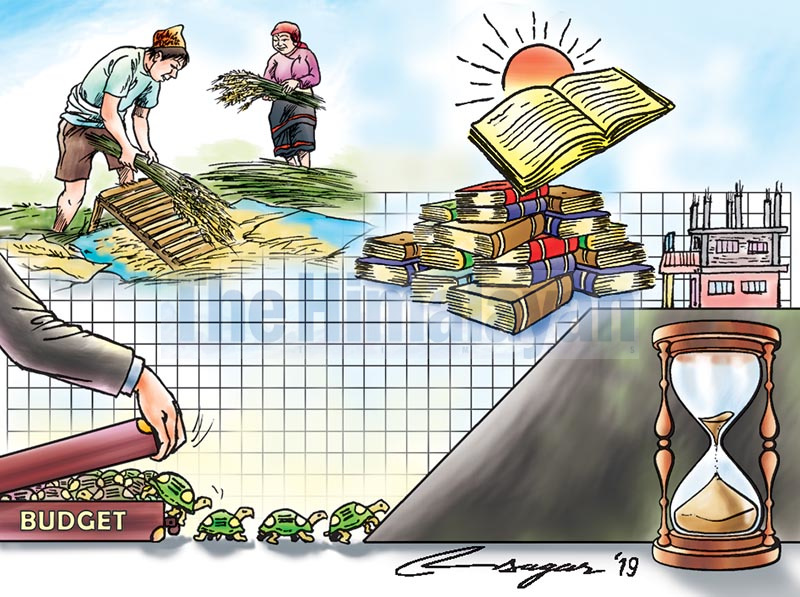

Nepal needs to find ways to manage its resources optimally and productively and be able to get every rupee’s worth. So, it needs to focus on implementing the budget in sectors that can deliver the maximum outcome like agriculture and education

It’s that time of the year again when the government scrambles to spend its budget before the next budget is executed. Local journalists have given this annual phenomenon an apt moniker of “Asare Bikas”, implying the month of Asar in the Nepali calendar when the government flounders to spend its budget.

One can easily discern the kind of substandard and haphazard development that such an approach towards implementing the fiscal policy of the country delivers. This perennial practice also exacerbates the loanable funds crisis or the liquidity crunch that banks face each year due to the sluggish pace of spending on the part of the government.

This, in turn, has an unfavourable effect on interest rates and the monetary policy that vacillate wildly, as banks and financial institutions use this as a convenient excuse to pump up interest rates to the peril of the average citizens and the larger economy.

The budget for the year 2018-19 was to the tune of Rs 1.31 trillion, or USD 11.6 billion, an unprecedented amount for Nepal. The budget this size inherently raised expectations among the Nepali people, given the fact that the house is controlled by a stable majority government. But expectations came crashing down with the Financial Comptroller’s report on the government’s performance.

According to the Financial Comptroller General Office, the government has been able to spend only 38% of the Rs 313.99 billion, or USD 2.7 billion, the total capital expenditure allocated for the fiscal year 2018-2019. This means the government was not able to spend a whopping 62% of the capital budget, which is 23.96% of the total budget for the year. This is a dismal performance to say the least on the government’s part.

Comparison of the government’s capital spending this year to the past fiscal years further shows how cringe worthy the government’s performance has been this time. Capital expenditure in the year 2015- 16 amounted to 59% of the total allocation while it was 66% of the total allocation in 2016-17. In 2017-18, the capex was 79.74% of the total allocation.

What was already disconcerting about last year’s budget was its structure. Of the total budget, 64% was allocated to manage recurrent spending. Recurrent spending is similar to operating expenses for the country that include overhead costs like salaries for government employees and maintenance costs to manage existing projects.

Another 12% was allocated for financial management, which include activities like fulfilling the country’s debt obligations. And 23.95% of the total budget was allocated for capital expenditure, which are investments that the government makes in new projects and technology that carry the promise of future returns.

With the agricultural sector employing approximately 67% of the country’s population, the budget that was allocated for it was a meagre 3.5% of the total budget, which is Rs 40.14 billion, or USD 357.4 million.

Assuming the country’s population to be 28 million approximately, the government seems to have underestimated the needs of 18,760,000 people engaged in the sector. With the said allocation each person would roughly be getting only USD 19.05 in the agriculture sector, which is little to no help.

And although the education sector received a generous amount compared to other sectors in last year’s budget, which amounted to Rs 134.51 billion, or USD 1.19 billion, there has been a general trend of declining share earmarked for the education sector. The allocation stood at 10.23% in 2018-19, down from 18% in 2013-14. The figures allocated for education might have seen an increase, but the decline in the percentage shows how education might not be a priority for the government.

Nepal had a GDP of USD 24.47 billion in 2017-18.

The government had a target to achieve a GDP growth rate of 8% for the fiscal year 2018-19. However, according to the IMF estimates, the economy grew at a rate of 6.5% during the year. So, Nepal’s new GDP would be USD 2,607,767,9000, an addition of USD 1,607,679,000.

Budgets alone do not play a role in driving the economic growth of a country. But they do play a major role in inducing other variables that affect the growth rates in the GDP equation of C+ I + G + (X- M), where C stands for consumption, I for investments, G for government expenditure or the budget, X for exports and M for imports.

The budget does influence the other variables in the said equation and creates a positive and conducive environment for private investments and stimulate demand in the economy. The investment multiplier demonstrates that a change in government spending leads to a greater change, or a multiplied change or more than a proportionate change, in the resultant GDP or income of an economy.

Nepal aims to be a middle income country by 2030 and plans to graduate from a least developed country to a developing country by 2022. For that, Nepal needs to find ways to manage its resources optimally and productively and be able to get every rupee’s worth. So, it needs to focus on introducing and implementing the budget in sectors that can deliver the maximum outcome like agriculture and education. A myopic vision would mean being pound foolish and penny wise and is surely to cost the present and future generations dearly.