The City & its memory: We are losing them both

As we erase the remaining memories through indifference and inadequately thought-out development, the largest Himalayan metropolis, once celebrated for its advanced urban civilisation, is being transformed into environmental nightmare

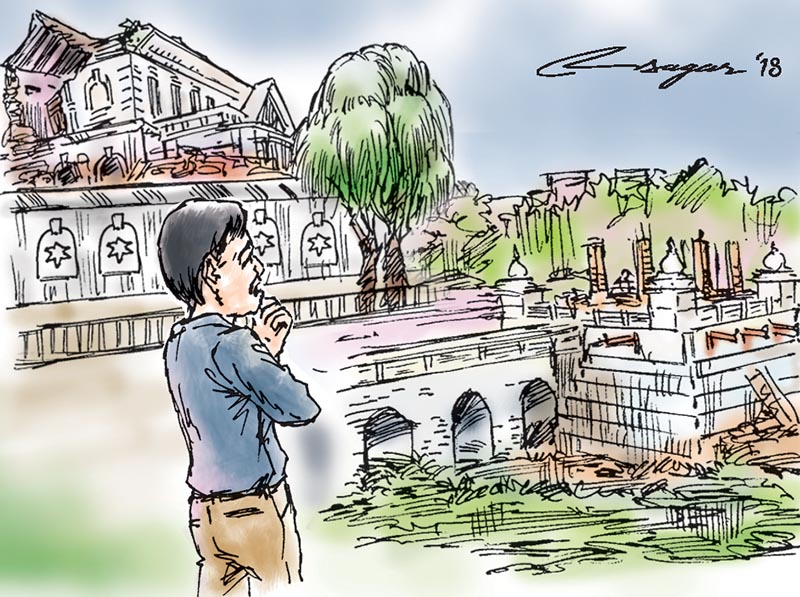

In the relentless drive to change the City, everyday a memory disappears as significant urban elements are thoughtlessly demolished in the pursuit of “development”. This begs the question: whether such memories have any further meaning for the residents of the City today? In a globalised world where information and technology rules, real memory gets replaced by the digital memory of the hard drives, as also the real experiences of a place get replaced by the virtual world of digital media. A city is a constantly evolving phenomenon, therefore subject to continuous transformation over time. I am not advocating that we must save all the physical elements/ buildings from the past. As I was driving back through Tripureshwor chowk the other day, I experienced a strange sense of unease. Then I realised that the Kanti Ishwari School building which sat in its large compound in Tripureshwor surrounded by beautiful trees was gone — the cluster of trees was also gone. As I passed the New Road Gate, the once familiar elegant gracious neo-classical architecture of the Military Hospital was replaced by a hideous box of concrete and glass. The façade, though rebuilt later as a paste over the box, somehow clings on for survival. As I passed the perpetually deformed temple at Ranipokhari, I confronted a further sense of unease. The Durbar High School was gone too. I wondered if it would be the turn of the elegant Tri-Chandra College building and Ghantaghar next.

But if significant urban elements which represent “real memories” of a place disappear, what will connect our time in this city to the past and to the future generations?

Every city has its own unique story where the significant elements that constitute its memory create the sub-plots within the story. Such elements have great value as they establish the city’s spirit, imagery, identity and cultural life.

They link the many times that the city and its citizens have lived to arrive at the present. When we visit other cities in distant lands, it is the elements, which represent memories of the place, that we cherish the most. As our city expands and modernises, new infrastructure should find their own space alongside the elements which represent the City’s’ memory, not overwhelm.

I remember that even a decade ago the stretch of road from Chaarkhaal to Dhobi Khola provided the experience of a distinctive and harmonious street façade. The continuous row of gracious individual façades offered a rare experience of a highly imageable street outside the historic city core. Then it suddenly disappeared a few years ago in the City’s drive of road widening to accommodate more vehicular traffic. The unique urban civilisation that flourished in the Valley for thousands of years was a direct result of the extensive river system that the Valley has been blessed with. The rivers drained the cities and irrigated the fertile land. This entire river system was dotted with many important sites where elaborate ghats were constructed along with beautiful temples and religious complexes, creating settings for rituals and festivals observed even today. These elaborate constructions were really a celebration of the unique relationship that the river system formed with the cities and towns of the Valley.

Today as urban development intensifies along the river banks, rivers are slowly becoming urban gutters, while the ghats and their accompanying complexes are slowly disappearing amidst the frenzy to build new infrastructure and buildings. The list goes on.

Many beautiful courtyards and streets in the inner cities have disappeared altogether. Historically important structures like the Chaarkhaal Adda await their demise. The Louis Kahn-designed family planning building (now Ministry Of Health) has been deformed beyond recognition. Future generations will probably never know that the world’s most famous architect of his time actually designed and built a building in Kathmandu.

The CEDA building in the Kirtipur TU campus, a very important work of modern architecture in Kathmandu, once captured the imagination of many scholars who used it. But now it lies unused and uncared, staring at an imminent crisis which could be its eventual demise. Yet we relentlessly pursue the illusive “world class” in building architecturally sub-standard buildings.

Amidst all this, there are some “real memories” in this once beautiful City that have survived and have been spared. The City Hall on the eastern side of Tundikhel was due for demolition as the large land it sits on was deemed “too valuable” for an aging auditorium. What saved it was the last SAARC conference. The old Taragaon Hotel, designed by the renowned Austrian architect Carl Pruscha, was due for demolition too, but was later renovated and now serves as a museum and an important cultural space.

While the earthquake destroyed our heritage at an epic scale, our own conflicting policies, insensitivities and inabilities have accelerated the disappearance of remaining important memories of the City.

As we relentlessly erase its remaining memories through indifference and inadequately thought-out development, the largest Himalayan metropolis, once celebrated for its advanced urban civilisation, is being transformed into an environmental nightmare with large parts resembling giant slums.

Shah is an architect