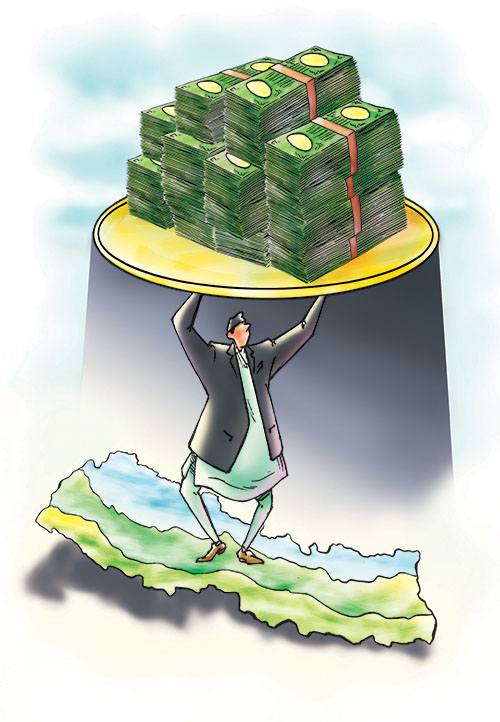

Towards provincial fiscal autonomy

KATHMANDU, SEPTEMBER 13

With the changed context of federalism, the sub-national governments – province and local - are recognised as autonomous spheres and have delineated legislative powers. While some responsibilities are exclusively assigned to the three orders of government, others are concurrent in nature. Based on this very principle, the Constitution has provided grounds for both expenditure responsibilities and revenue rights to and among the tiers.

Nepal retains a framework wherein the key revenue sources rest with the federal government. Although the local governments still hold the exclusive right to levy taxes under four headings - wealth tax, house rent tax, land tax and business tax – the provincial governments only have agro-income tax in their entirety. To top it off, Nepal has no history of collecting agro-income tax.

With this highly constrained and weak fiscal base coupled with the provincial governments’ weak administrative and revenue generation capacity, a vertical fiscal imbalance is inevitable. The copious amount of revenue lodging in the central government’s coffers owing to its high tax bases will call for a significant volume of transfers to address this imbalance. Perhaps, this low tax system with ever-increasing financing need of the provincial governments will spur a vicious cycle of perpetual fiscal deficit as well as reliance on debt and transfers.

In a manner that ensures increased autonomy and reduced dependency, the provincial governments need to ensure that the tax revenue source is exploited to its full potential. Considering that agriculture in Nepal is characterised by low-income generation and highly volatile output, the provincial governments’ potential to maximise revenue from this source is dramatically limited. Nevertheless, the Constitution has mandated the imposition of agro-income tax, which makes it all the more pertinent to consider its implication.

The taxation of agricultural income in Nepal is a socially, economically and politically difficult matter. The initial rhetoric associated with agro-income tax is that it overlooks the notion that a significant part of the agricultural community comprises of small farmers, simply eking out subsistence living, who cannot bear the brunt of taxation. Another point of contestation is that the agro-sector, for the most part, is informal and is driven by cash-based transactions without a proper accounting framework. This impedes the assessment of the farmer’s actual income, which further hinders tax collection.

Having said that, with agro-income tax in place, it is not the small but the large farmers who will be taxed. The Ministry of Agriculture reports that the average annual income of a farmer approximates to Rs 82,500. In such a case, the imposition of the agro-income tax will not hold any significance to the small farmers as they, in all likelihood, will not make it to the lowest income tax slab. Also, the levying of an appropriate agro-income tax rate will remove the distinction between the income derived from the agriculture sector and the non-agriculture sector. This will thus conform to the principle of horizontal equity as those earning an equivalent level of income across sectors will be taxed in like manner.

Against the backdrop of subsistence agriculture and sectoral informality, the government in the form of input subsidies, credit and extension services injects bumper payouts to support the agro-sector. However, the current practice of over-subsidising yet under-taxing agriculture not only induces fiscal indiscipline but also disproportionately benefits the large farmers as it is practically impossible to identify the small farmers – the real beneficiaries - operating in the shadow economy. The benefits of taxing rather than subsidising the agro-sector rest upon the fact that taxing will bring the farmers from the informal to the formal sector and allow them to demand improved services in the form of better road infrastructure, access to credit and insurance, output market, enhanced agricultural education and research. This will further enable them to demand accountability from the government than to remain mute recipients of subsidies.

Likewise, as agriculture is a major contributor to the GDP in Nepal, the imposition of agro-income tax will raise substantial revenue to finance the expenditure to improve agricultural infrastructure. The agro-income tax will mitigate the discrepancy between agriculture’s contribution to GDP and tax whilst resulting in an improved tax to GDP ratio. Simply put, the large untaxed potential of the agro-sector can be leveraged by taxing the income of the farmers, which will allow the government to acquire sufficient funds. Besides, the exemption from agro-income tax develops a channel for tax evasion as it encourages individuals to launder the non-agricultural income as agricultural income. Hence, taxing will plug the loophole that exploits agriculture as a tax shelter.

The establishment of a streamlined mechanism for collection of agro-income is long overdue. As it currently stands, provincial governments have virtually no other tax revenue source apart from agro-income tax. The reliance on the central government that is to follow will ultimately undermine the concept of federalism and curtail provincial autonomy.

Chaudhary is a researcher at Samriddhi Foundation and can be reached at ankshita@samriddhi.org