Transitional justice: Truth is its foundation

Transitional justice is a challenge by which we test ourselves, our vision of the future and the kind of society we want to build out of the rubble of the decade of conflict

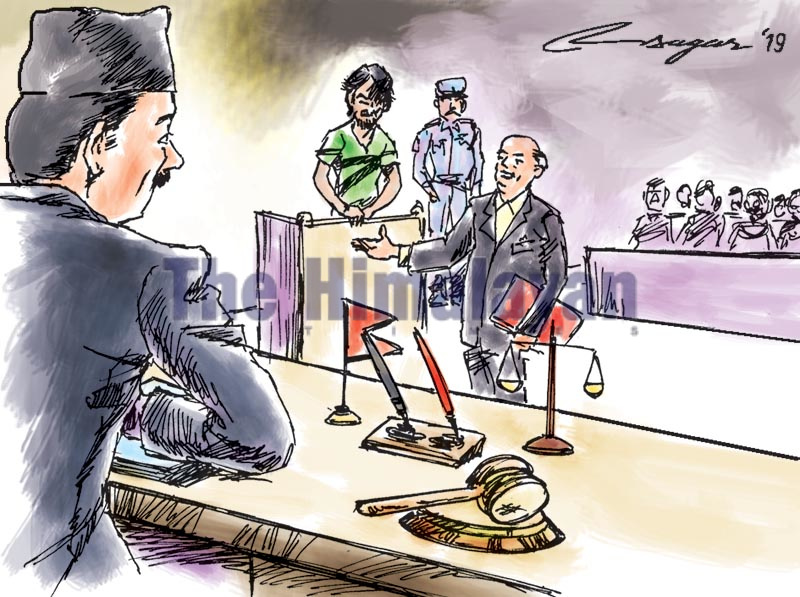

They say that ‘you live and learn’. What does it take for a society to learn about the importance of truth? The whole foundation of transitional justice (TJ) is the truth. Based on that truth, we remember what actually happened here in our country. Based on that truth, we bring justice and reparations and remedy to those who have suffered, victims and survivors. Based on that truth, we reform and improve our institutions and practices to reduce the chances of that kind of disaster happening to us once again.

I want to look at what happened on November 21, 2006 – when the Comprehensive Peace Agreement was signed - through the prism of the truth and hope it can be a learning experience. I apologise in advance if I offend anyone, but clearly in Nepal today, the truth is inconvenient to some. But without the truth, we will be condemned to go around in circles like a dog or a bear on a short chain, which first gets angry and then goes mad.

Before I begin my diary of November 21, let me just make one thing clear; transitional justice is a great and inevitable opportunity for us to learn from the past to make a better future. It is not a gesture of revenge but a signpost of hope for all of us. It is not an obstacle on our path towards stability and prosperity; it is that path! TJ is a challenge by which we test ourselves, our vision of the future and the kind of society we want to build out of the rubble of the decade of conflict. Everyone, including our leaders and diplomatic friends, must understand this.

Remembrance is the least we can offer to honour our dead, tortured, all our victims. But only the victims and civil society chose to remember the 13th anniversary of our rediscovery of peace. If the victims hadn’t organised events and journalists marked the day, it would have passed in silence, buried like the 17,000 of our compatriots who will never see another anniversary.

We will never know what positions politicians took on TJ during the CPA negotiations in 2006 as it all took place in private, behind closed doors, without civil society’s participation, no women, just high-caste men drinking whiskey in smoky rooms. But from now, we can insist that there will be transparency and the truth. They all now claim to have constantly defended the truth process even if the experience of the 13 years could make us doubt this from all of them.

Our peace process is a great event in our history, and we must cherish it and keep it alive. But we must examine it with the truth. Let us not forget that in April last year, at the request of our political leaders, an embassy in Kathmandu brought a secret political mission from Colombia in the hope of finding a magic solution to the issue of TJ, that is, how to make it go away with no political damage, with no custodial sentences. But the Colombians who were brought, in wisdom and honesty, told our leaders that there is no secret to their negotiations. In disgust, our leaders sent them back to South America.

Since 2014, the Supreme Court had clearly said what changes needed to be made to the TJ Act to make it conform to our laws. The UN did the same with regard to international law. Our politicians have had five years to bring an amendment, but nothing has happened. The previous commissions failed in part due to lack of supporting legislation. Now our leaders say ‘trust us’, this time the commissions will work. But we have been saying for years that we need the amendment before the appointments, and then participation of civil society in the selections, as per international standards. ‘Trust us,’ they said when they set up a selection committee and then prevented it from doing its work until the decision had been fixed by the leaders in private meetings. Why should we trust any new commissions when it is clear we cannot even trust the selection committee?

Here are my truths: transitional justice is unavoidable, but it cannot happen until the civil society and, in particular, the victims have trust in the process. That trust can only come with transparency on the part of the leaders and genuine participation in the process for victims and human rights groups. The arguments our leaders put forward on November 21 might have worked in 2006, but after 13 years of disappointments and deception, they no longer hold in 2019.

One thing our leaders agree on is that they do not want Universal Jurisdiction, international justice, but they forget that this only ever happens when national measures have failed or there is no political will amongst the politicians and the judiciary. It is the same with the TJ. Thus we have only two alternatives: Set up a people’s truth process, to allow an agreed version of what happened to come out through victims’ testimonies. Second, call for international help, which basically means UN expertise. Victims are tired of being lied to, and our leaders risk paying the price due to loss of credibility.

The eyes of the world are on Nepal, and most people want us to succeed. The longer the TJ process remains stuck in the mud, the more we will look like a nation which doesn’t know what it wants, what direction we are seeking. Not just the international human rights community, but potential investors will not be encouraged if we do not show clear determination to tell the truth about the past and learn lessons that allow us to strengthen the rule of law.

Ansari is a member of the National Human Rights Commission