Water crisis Formidable challenges

Ultimately, national leadership must be made fully aware that insensitivity

towards national water management is a perfect recipe for security risk in

the long term

There are conflicting claims on whether humans can do anything about climate change or not. But because of our reliance on natural resources for living and economic progress, developing nations like Nepal suffer the most.

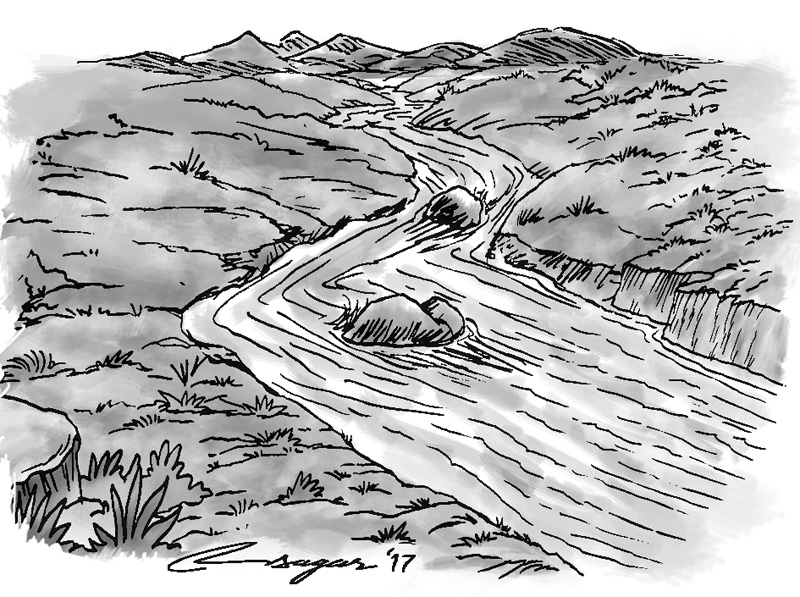

Rapidly melting glacial lakes, ever expanding barren hills and shortage of water in most of the usual population centers are some of the significant but late indications blinking as an alarming climatic traffic light.

It is a ticking time bomb that in the long term can incubate formidable security challenges.

Scientists believe global warming has contributed to the rise in temperature. Hence, the polar ice is melting and the sea level is rising. Since Nepal relies on water flowing from snow fed mountains in the north it will undoubtedly be hard hit. We have no choice but to face the climate change squarely.

However, we must do everything humanly possible to ease the suffering of the Nepalese people and safeguard their right of security guaranteed by the constitution.

During my service, I had an opportunity to visit Sri Lanka and the Netherlands and closely felt the sense and attitude of people and leaders of those nations about water.

It will be relevant for Nepal to stimulate our leadership’s appetite for change in attitude in formulating a needful comprehensive strategy on water that will enhance food security and ensure human security.

Many believe June is the best time to visit the East Coast in Sri Lanka. Fortunately, on 27 June 2014, I happened to be there. Wiping out my personal comprehension of conflict in Sri Lanka, my enthusiasm to read the terrain, while flying diagonally from Colombo to the Yala National Park situated in the southeast region at Uva province ended in great surprise.

Lush green near nap-of-the-earth flight and frequently encountering blue ponds and lakes of varied size made me think about my country, Nepal, the second richest country in inland water resources in the world.

Flying over Sri Lanka, I recall the moment while I sat in front of a computer at Rijkswaterstaat, the Netherlands on 20 June 2010. We were introduced to a “Serious Gaming” on water management to keep their nation safe from high water and ensuring clean drinking water.

Containing sea water at the sea front and holding fresh water inland is an incredible task, and it obviously needs lots of technology and talent. But the success story of the Netherlands revolving around water can be replicated anywhere anytime.

In retrospect, I found myself among millions of Nepalese who are water stressed while annually approximately 220,000 billion cubic meters of water flow out through the rivers of Nepal.

If the people of Nepal are the center of gravity of every power in Nepal, why should they remain thirsty and why are their lands not sufficiently irrigated?

I could not remain tight lipped during that flight. So taking out the tightly worn ear-muffler, I ventured to ask my Sri Lankan counterpart, “What are those bodies of water, all along?”

I knew the sound of aircraft was too loud for him to understand my question and answer me accordingly. “It is a long story. I will tell you when we land,” he shouted loudly on my ear and saw my nodding.

Later that evening, I sat with him for elaborated talks. He quoted King Parakrama Bahu the Great’s word, “Not one drop of water shall reach the sea without first serving man. You know, we are surrounded by sea that holds salty water we can’t drink and use for agriculture either.

Those bodies of water you saw are the footprints of our forefathers who have done their utmost to hold inland fresh water.” When he asked, “But you have plenty of fresh water in Nepal, no?” I remembered the water stress in Nepal marked by long empty queues of water pots.

As of now for every ordinary people, Nepal can be characterized as a nation where a justice seeker like the late Nanda Prasad Adhikari has to wait in the mortuary shelf posthumously for justice, doctors like Govinda KC have to sit for fast-unto-death to be heard and social entrepreneurs like Mahabir Pun denied support for innovation.

No leaders or relevant officials have time to ponder on my less than a thousand word narration flagging a necessity to create a comprehensive long-term strategy to manage 220,000 billion cubic meters of water.

But ultimately, national leaders must be made fully aware that insensitivity towards national water management is a perfect recipe for security risk in a longer term. Therefore, they must be responsible for creating a comprehensive strategy and held accountable on what they do and fail to do about national waters.

Honestly, let us seek a single leader for whom our descendants would proudly be quoting him saying, “Not one drop of water shall cross Nepal without first serving the Nepalese people”.

Nepal needs to work on a war footing to save the pristine nature and precious water. It is obvious, when water from the Melamchi hits our tap, it would ease the thirst of Kathmandu residents, but what about the rest of the nation?

“A stitch in time saves nine” so let’s open a right trajectory by changing our collective attitude to create a comprehensive strategy on water management and confront the climate change.

Let’s keep water as a symbol of peace and prosperity--not a reason of insecurity and instability.

Sijapati is a former soldier of the Nepal Army who served in the UNHQ, New York