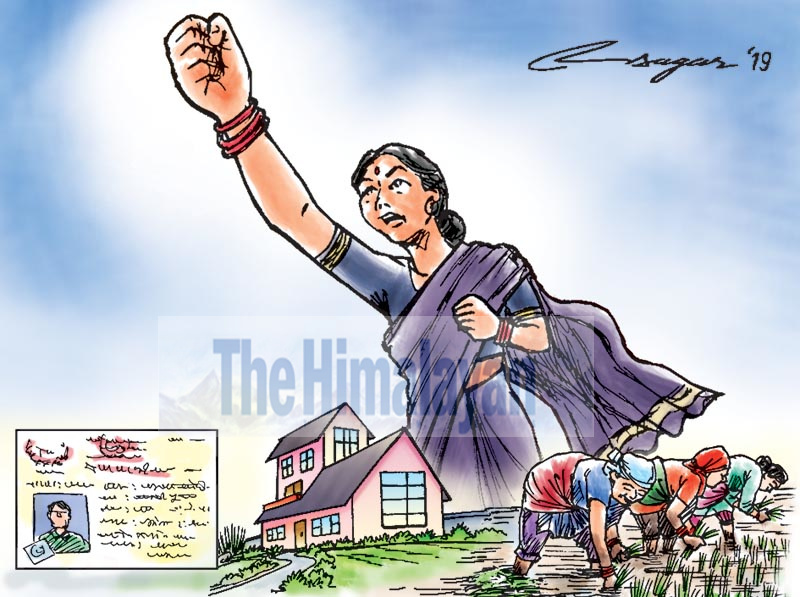

Women’s empowerment: Still an uphill task

Research has shown the importance of variables, such as education, resources, gender-friendly laws, among others, in transforming a woman’s image from ‘ill-being’ to ‘capable-being’

Women’s empowerment is a slogan aimed at ensuring gender equality by providing equal rights to women. It is a kind of compensation for all the discriminations meted out against women. However, the variables for measuring women’s empowerment are still debatable.

The term empowerment implies enabling one to make a choice to live a quality life and fight against any element that prevents their freedom and empowerment. Unfortunately, it is still a far cry for majority of the women today. Denial of educational opportunities, political freedom, mobility and gender equality marginalise women from a very young age. This not only diminishes their quality of life and capabilities but also makes them unable to become change agents. It is an uphill battle for the Nepali society where the patriarchal mindset is prevalent with structural and cultural violence that deny women opportunities.

Government, national and international agencies, rights activists and many others have been working to enrich women’s life and enhance their decision-making power since the 1990s. But empirical analyses of the achievements of past initiatives are not astounding. Research has shown the importance of variables, such as education, resources, gender-friendly laws, among others, in transforming a woman’s image from ‘ill-being’ to ‘capable-being’.

In particular, education helps women foster their ability to grab political and economic opportunities as well as change their cognitive ability and develop the core capabilities to fight with the discriminating social structures. In our country, women’s literacy rate is not very inspiring. As per the National Census Report 2011, the literacy rate of the male population aged above five is 75.1 per cent while the literacy rate of the female population is 57.4 per cent, indicating a huge gap between the genders.

Another barrier to women’s empowerment is their lack of access to economic resources. It is evident that there is a correlation between poverty and empowerment. Women’s lack of means to meet their basic needs often rules out their ability to exercise meaningful choice. Nepal being an agricultural country, majority of the women are still dependent on agriculture, and their valuable time is spent in the fields and in bearing children.

The participation of women’s labour in household and agriculture is not paid, therefore, it is not counted as work that contributes to improving the country’s GDP. Similarly, majority of Nepali women do not own property, such as a house or land. The National Census Report 2011 maintains that only 19.71 per cent households have female ownership over land and property. This could be one of the reasons behind women’s lesser engagement in day-to-day economic activities.

Following the provisions in the new constitution, citizenship law was amended to grant rights to a woman to confer citizenship on her kids through her lineage, but there is some opposition to this.

Domestic violence and marital rape have been criminalised, but women filing cases against their own husbands are rare. Similarly, the government is yet to develop a reliable state mechanism to support victims of domestic violence and trafficking.

The presence of the state as a guardian of women is lacking. Instead of legal support from the government mechanism, women are systematically troubled by a faulty government mechanism itself, which deprives them of justice.

Gender quota was one of the progressive ways of empowering women socially and politically. However, its replication in the society is not very encouraging. Due to structural and cultural violence, even women lawmakers of the Constituent Assembly (CA) had faced discrimination, discouragement and humiliation from their male parliamentarians. Many women parliamentarians complained that they were not allocated enough time to give their comments and suggestions during the various discussions held in the course of constitution-drafting process. They were not trusted as having wisdom and competency.

Since the first five-year plan, gender and women’s empowerment have remained one of the priority areas of the government. A popular saying goes like this: ‘Give a man a fish and you feed him for a day, teach a man to fish and you feed him for a lifetime’. Women are demanding the government teach them to catch fish to empower themselves for a lifetime.

The government has introduced the draft of the 15th Five-year Plan, which states that it will develop a systematic database to measure gender equality and empowerment, which will verify the empowerment level of women. The draft has a chapter on ‘gender equality and women’s empowerment’ with a commitment to enhancing gender equality and women’s empowerment. This will be done by preparing sector-wise policy, laws and programmes relating to gender equality, following a gender-accountable governance system, institutionalising a gender-accountable budget allocation system, giving priority to socially backwards and marginalised women for economic empowerment and social transformation, and combatting gender-based violence. The government’s commitment sounds praiseworthy, but its application and success are a big challenge without first addressing various other issues related to the development of women’s capabilities.