81 migrant children separated from families since June

WASHINGTON: The Trump administration separated 81 migrant children from their families at the US-Mexico border since the June executive order that stopped the general practice amid a crackdown on illegal crossings, according to data provided by the government to The Associated Press.

Despite the order and a federal judge’s later ruling, immigration officials are allowed to separate a child from a parent in certain cases — serious criminal charges against a parent, concerns over the health and welfare of a child or medical concerns. Those caveats were in place before the zero-tolerance policy that prompted the earlier separations at the border.

The government decides whether a child fits into the areas of concern, worrying advocates of the families and immigrant rights groups that are afraid parents are being falsely labeled as criminals.

From June 21, the day after President Donald Trump’s order, through Tuesday, 76 adults were separated from the children, according to the data. Of those, 51 were criminally prosecuted — 31 with criminal histories and 20 for other, unspecified reasons, according to the government data.

Nine were hospitalized, 10 had gang affiliations and four had extraditable warrants, according to the immigration data. Two were separated because of prior immigration violations and orders of removal, according to the data.

“The welfare of children in our custody is paramount,” said Katie Waldman, a spokeswoman for the Department of Homeland Security, which oversees U.S. immigration enforcement. “As we have already said — and the numbers show: Separations are rare. While there was a brief increase during zero tolerance as more adults were prosecuted, the numbers have returned to their prior levels.”

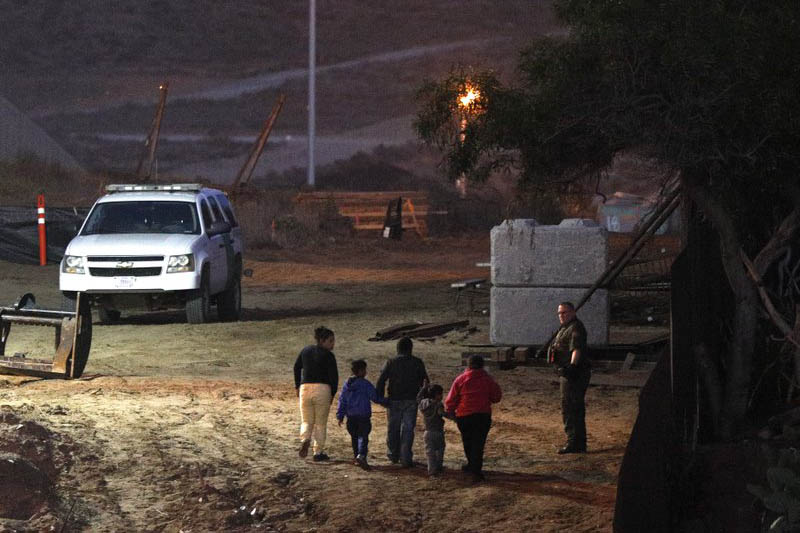

At its height over the summer, more than 2,400 children were separated. The practice sparked global outrage from politicians, humanitarians and religious groups who called it cruel and callous. Images of weeping children and anguished, confused parents were splashed across newspapers and television.

A federal judge hearing a lawsuit brought by a mother who had been separated from her child barred further separations and ordered the government to reunite the families.

But the judge, Dana Sabraw, left the caveats in place and gave the option to challenge further separations on an individual basis. American Civil Liberties Union attorney Lee Gelernt, who sued on behalf of the mother, said he hoped the judge would order the government to alert them to any new separations, because right now the attorneys don’t know about them and therefore can’t challenge them.

“We are very concerned the government may be separating families based on vague allegations of criminal history,” Gelernt said.

According to the government data, from April 19 through Sept. 30, 170 family units were separated because they were found to not be related — that included 197 adults and 139 minors. That could also include grandparents or other relatives if there was no proof of relationship. Many people fleeing poverty or violence leave their homes in a rush and don’t have birth certificates or formal documents with them.

Other separations were because the children were not minors, the data showed.

During the budget year 2017, which began in October 2016 and ended in September 2017, 1,065 family units were separated, which usually means a child and a parent — 46 due to fraud and 1,019 due to medical or security concerns, according to data.

Waldman said the data showed “unequivocally that smugglers, human traffickers, and nefarious actors are attempting to use hundreds of children to exploit our immigration laws in hopes of gaining entry to the United States.”

Thousands of migrants have come up from Central America in recent weeks as part of caravans. Trump, a Republican, used his national security powers to put in place regulations that denied asylum to anyone caught crossing illegally, but a judge has halted that change as a lawsuit progresses.

The zero-tolerance policy over the summer was meant in part to deter families from illegally crossing the border. Trump administration officials say the large increase in the number of Central American families coming between ports of entry has vastly strained the system.

But the policy — and what it would mean for parents — caught some federal agencies off guard. There was no system in place to track parents along with their children, in part because after 72 hours children are turned over to a different agency, the Department of Health and Human Services, which has been tasked with caring for them.

An October report by Homeland Security’s watchdog found immigration officials were not prepared to manage the consequences of the policy.

The resulting confusion along the border led to misinformation among separated parents who did not know why they had been taken from their children or how to reach them, longer detention for children at border facilities meant for short-term stays and difficulty in identifying and reuniting families.

Backlogs at ports of entry may have pushed some into illegally crossing the US-Mexico border, the report found.