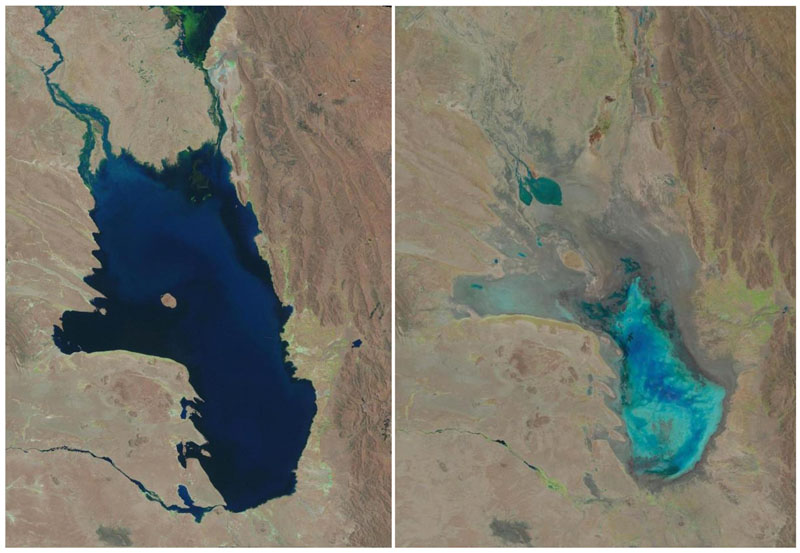

Disappearance of Bolivia's No. 2 lake a harbinger

UNTAVI: Overturned fishing skiffs lie abandoned on the shores of what was Bolivia's second-largest lake. Beetles dine on bird carcasses and gulls fight for scraps under a glaring sun in what marshes remain.

Lake Poopo was officially declared evaporated last month. Hundreds, if not thousands, of people have lost their livelihoods and gone.

High on Bolivia's semi-arid Andean plains at 3,700 meters (more than 12,000 feet) and long subject to climatic whims, the shallow saline lake has essentially dried up before only to rebound to twice the area of Los Angeles.

But recovery may no longer be possible, scientists say.

"This is a picture of the future of climate change," says Dirk Hoffman, a German glaciologist who studies how rising temperatures from the burning of fossil fuels has accelerated glacial melting in Bolivia.

As Andean glaciers disappear so do the sources of Poopo's water. But other factors are in play in the demise of Bolivia's second-largest body of water behind Lake Titicaca.

Drought caused by the recurrent El Nino meteorological phenomenon is considered the main driver. Authorities say another factor is the diversion of water from Poopo's tributaries, mostly for mining but also for agriculture.

More than 100 families have sold their sheep, llamas and alpaca, set aside their fishing nets and quit the former lakeside village of Untavi over the past three years, draining it of well over half its population. Only the elderly remain.

"There's no future here," said 29-year-old Juvenal Gutierrez, who moved to a nearby town where he ekes by as a motorcycle taxi driver.

Record-keeping on the lake's history only goes back a century, and there is no good tally of the people displaced by its disappearance. At least 3,250 people have received humanitarian aid, the governor's office says.

Poopo is now down to 2 percent of its former water level, regional Gov. Victor Hugo Vasquez calculates. Its maximum depth once reached 16 feet (5 meters). Field biologists say 75 species of birds are gone from the lake.

While Poopo has suffered El Nino-fueled droughts for millennia, its fragile ecosystem has experienced unprecedented stress in the past three decades. Temperatures have risen by about 1 degree Celsius while mining activity has pinched the flow of tributaries, increasing sediment.

Florida Institute of Technology biologist Mark B. Bush says the long-term trend of warming and drying threatens the entire Andean highlands.

A 2010 study he co-authored for the journal Global Change Biology says Bolivia's capital, La Paz, could face catastrophic drought this century. It predicted "inhospitable arid climates" would lessen available food and water this century for the more than 3 million inhabitants of Bolivia's highlands.

A study by the German consortium Gitec-Cobodes determined that Poopo received 161 billion fewer liters of water in 2013 than required to maintain equilibrium.

"Irreversible changes in ecosystems could occur, causing massive emigration and greater conflicts," said the study commissioned by Bolivia's government.

The head of a local citizens' group that tried to save Poopo, Angel Flores, says authorities ignored warnings.

"Something could have been done to prevent the disaster. Mining companies have been diverting water since 1982," he said.

President Evo Morales has sought to deflect criticism he bears some responsibility, suggesting that Poopo could come back.

"My father told me about crossing the lake on a bicycle once when it dried up," he said last month after returning from the UN-sponsored climate conference in Paris.

Environmentalists and local activists say the government mismanaged fragile water resources and ignored rampant pollution from mining, Bolivia's second export earner after natural gas. More than 100 mines are upstream and Huanuni, Bolivia's biggest state-owned tin mine, was among those dumping untreated tailings into Poopo's tributaries.

After thousands of fish died in late 2014, the Universidad Tecnica in the nearby state capital of Oruro found Poopo had unsafe levels of heavy metals, including cadmium and lead.

The president of Bolivia's National Chamber of Mining, Saturnino Ramos, said any blame by the industry is "insignificant compared to climate change." He said most of the sediment shallowing Poopo's tributaries was natural, not from mining.

In hopes of bringing it back, Morales' government has asked the European Union for $140 million for water treatment plants for the Poopo watershed and to dredge tributaries led by the Desaguadero, which flows from Lake Titicaca.

Critics say it may be too late.

"I don't think we'll be seeing the azure mirror of Poopo again," said Milton Perez, a Universidad Tecnica researcher. "I think we've lost it."