Scientists in new push to control cancer before curing it

LONDON: Cancer scientists in Britain are launching what they call the world's first "Darwinian" drug development programme in a bid to get ahead of cancer's ability to become resistant to even the newest treatments and recur in many patients.

While not abandoning the search for an ultimate cure, the "anti-evolution" project will re-focus on turning cancer into a disease controllable with drugs for many years.

This would be a little like HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, the scientists told reporters at a briefing.

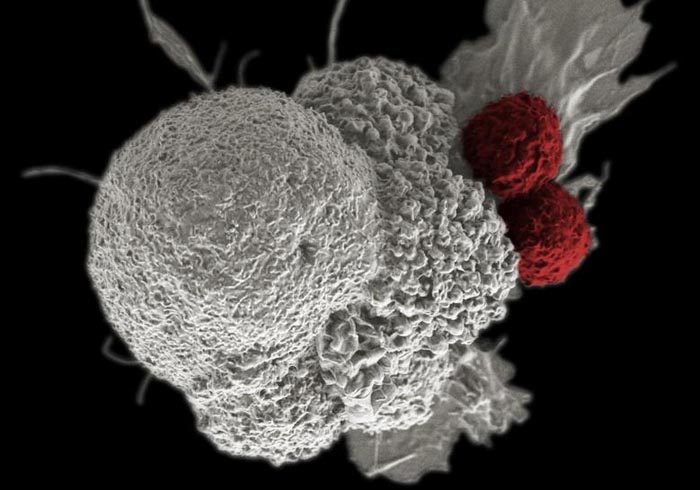

"Cancer's ability to adapt, evolve and become drug-resistant is the cause of the vast majority of deaths from the disease and the biggest challenge we face in overcoming it," said Paul Workman, chief executive of Britain's Institute of Cancer Research (ICR) - a charity and research institute which will lead the new Centre for Cancer Drug Discovery.

The centre, funded with 75 million pounds ($96.5 million) from the ICR, will "seek to meet the challenge of cancer evolution head-on", Workman said, by blocking its process of evolution.

Teams at the new centre will initially focus on two possible paths to doing this.

The first, known as "evolutionary herding", involves selecting an initial specific treatment that forces cancer cells to adapt in a way that makes them highly susceptible to a second drug, or pushes them into an evolutionary dead end.

The second will explore a possible new class of drugs to target cancer's ability to evolve and become resistant to treatment. These potential drugs would be designed to block the action of molecules called APOBEC proteins, found in the body's immune system.

Researchers hope a new class of APOBEC inhibitors could be developed and given alongside targeted cancer treatments to try and keep cancer at bay for much longer.

Combination therapies using multiple current or new treatments will also be explored, Workman said.

Olivia Rossanese, a specialist in cancer drug discovery who will head the new centre's biology team, said the idea was to build a global hub of expertise in anti-evolution therapies so scientists could "stop playing catch-up" with cancer.

"This Darwinian approach to drug discovery gives us the best chance yet of defeating cancer," she said, "because we will be able to predict what cancer is going to do next and get one step ahead."