Hit hard by pandemic, Sherpa widows face uphill battle

KATHMANDU, JULY 7

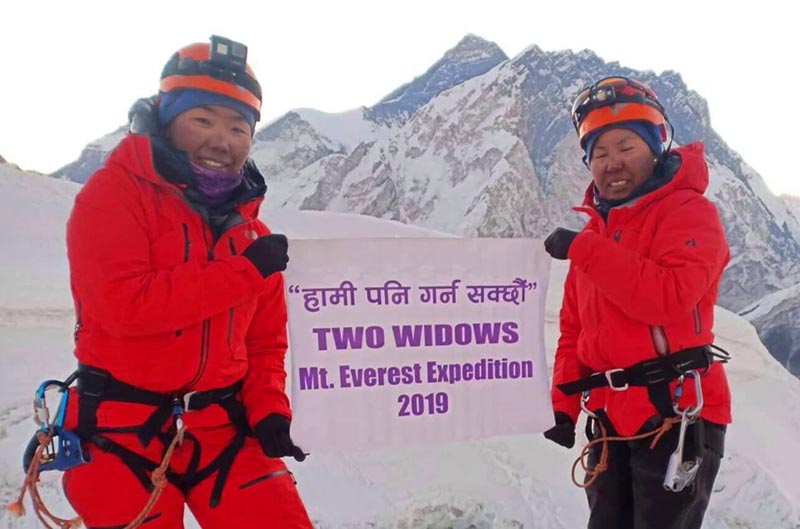

After conquering Mount Everest and shattering taboos, two Nepali Sherpa widows face a new challenge, the coronavirus pandemic, which has shut down all climbing and trekking activities rendering them jobless.

Nima Doma Sherpa and Furdiki Sherpa made global headlines when they scaled the 8,850 metres mountain last year to honour their climber husbands and raise awareness about social discrimination of widows in the conservative Nepali society. A year on, the women, who guide foreign trekkers, said they had not made any money since Nepal closed its mountains and trekking destinations in March - the start of the popular hiking season - to stem the spread of the virus.

“I’m digging into my savings to feed two young children and my elderly mother. I don’t have much left now,” said Nima Doma, 36.

Nima Doma and Furdiki, who belong to the ethnic group of Sherpas renowned for endurance and an ability to operate at high altitudes, go by their first names like most other Sherpas, but are not related.

Both lost their husbands in climbing disasters on Mount Everest in 2013 and 2014.

The lockdown has left thousands of guides in limbo. According to hiking officials about 200,000 people every year work as guides, porters and other staffers for trekkers in Nepal, home to eight of the world’s 14 highest mountains and Annapurna base camp, one of the busiest destinations for adventure tourists.

The virus struck just when the guides were making final preparations for the trekking season, and officials say post-monsoon hiking, which starts in September, looked uncertain as the coronavirus peak could still be weeks away.

Furdiki, 44, who has three children, said her ‘biggest worry’ was how to survive if trekking did not begin soon. “Even if the lockdown is over now the trekking business may take a couple of years to revive. Trekkers may not return early. This means we may not get work early,” she said.

A trekking guide, less exposed to risks than those going to high mountains, makes about USD 25 plus tips from clients per day in a season that lasts for a month.

The outbreak also delayed the women’s plans to open a charity to provide fellow widows with training to get jobs. Widows are generally expected to mourn until they die in South Asia, renouncing colourful clothes, jewellery, rich food and even festivals, according to women’s rights experts. Widows in developing countries are routinely disinherited, enslaved or evicted by their in-laws, accused of witchcraft or forced to undergo abusive sexual rituals.

Nima Doma said she would return to her village near Everest and grow vegetables if trekking did not resume soon, but she was concerned that there were no good schools by her native home.

“I want to avoid that as far as possible,” she said. “I’m staying back in Kathmandu despite difficulties, waiting to send the children back to school.”