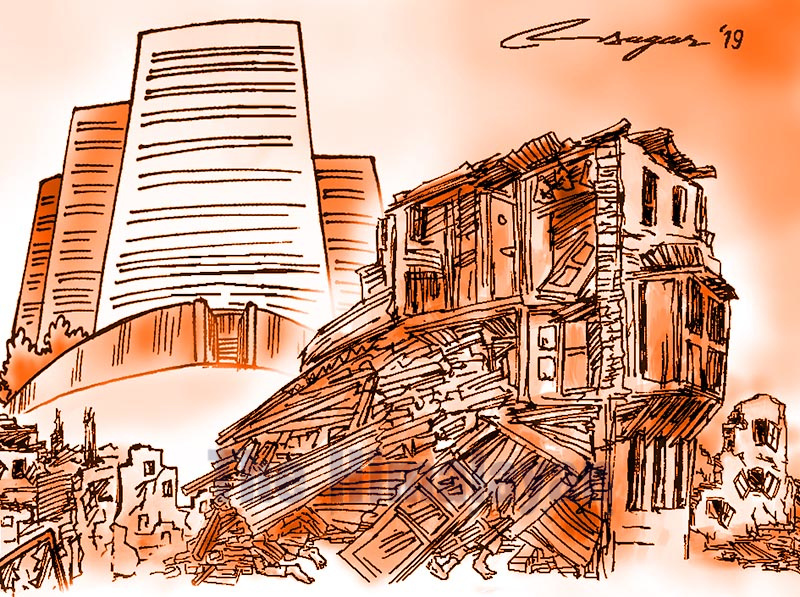

Building back safer: Local, sustainable solutions needed

Nepal is overly focussing on earthquake disaster only; however, a large number of houses are damaged by other disasters, such as floods, landslides and fires, among others. Thus, the challenge of building safe settlements cannot be solely based on earthquakes. It is high time Nepal switched to multi-hazard resilience on a local scale. This will definitely bring forth some local yet sustainable and resilient solutions

In every nook and cranny of the country,’earthquake-resistant construction technology’ were the buzz words after the cataclysmic Gorkha Earthquake rattled the central, eastern and parts of western Nepal. There was a flood of national and international proposals, leading to a stalemate in kicking off the reconstruction process, although this was appreciable in terms of building back safer. The process was undecided, not knowing whether to work on innovation or to approve the models proposed by people from across the field to kick off the reconstruction.

There was a hurried reincarnation of models that used the phrase ‘earthquake-resistant’ despite being no more than minor modifications of whatever was in existence already.

A recent research paper entitled ‘Speed and quality of recovery after the Gorkha Earthquake 2015 Nepal’, published in the International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, dissects the pros and cons of the endorsed technology- ,quoting the voices of the public and experts. Based on a spatially covered survey, the paper concludes that the biggest little missing aspect of the post-earthquake reconstruction was the missed opportunity to build back safer. The conventional build back better concept may not fundamentally address the dynamics of reconstruction and the rehabilitation landscape. Thus, researchers today are concerned more with building back safer rather than flat endorsement and prototypic execution of housing construction.

The multi-faceted challenges in the socio-economy were analysed in the research, which led to conclude that 90 per cent of the reconstruction was completed within four years of the earthquake. A grim fact is that most of the reconstructed houses in the rural neighbourhoods are moderately to barely occupied due to their confined sizes (usually two rooms) and are used for cattle or as stores.

Interestingly, the research highlights that public awareness in terms of housing construction and changing landscape of earthquake-resistant construction was rooted even in the remote locations, and most of the beneficiaries felt safe in the newly constructed houses. In retrospect, the current understanding of seismic hazard in Nepal is not exhaustive, thus it would be too early to demarcate the minimally to moderately engineered constructions as earthquake-resistant constructions.

However, the bright side of the reconstruction is that people have started to believe in structural engineering practices probably due to their experience with an earthquake as well as mandatory regulations required to get financial benefits offered by the government.

The housing solution would have been mostly the localised model, which attracts the surrounding resources provided that safety and serviceability are guaranteed. However, the imported models and unregulated constructions — mostly in the rural affected areas — went against it.

The syndicated reconstruction models, at many locations, wiped out many majestic architectural forms, such as thatched roofing, slate roofing, rounded structural forms and many more. Aesthetics took a back seat due to déjà vu vulnerabilities of the existing housing forms, which were not exhaustive, and most of the aspects of aseismic constructions and features were undug.

It is likely that the generation transferal of knowledge after 1934, 1965, 1980 and 1988 earthquakes were almost forgotten. Understanding the vulnerability of buildings in Nepal is not complete until we incorporate the lessons of the 1934 and following earthquakes that hit various parts of the country and had a destructive impact on both lives and houses.

Spending on research will require historical studies as well as current understandings, which may provide a new narrative. Maybe the building codes need to be rewritten with deeper understanding of the seismic vulnerabilities of various structural forms. Not only are structural forms important, there must also be public awareness and compassion for improved if not earthquake-resistant building construction to ensure seismic safety of the existing as well as new constructions.

An earthquake will never be too little or too big to rock the structures, so sagacious constructions and localised endorsements are needed for now.

Since the Gorkha Earthquake in Nepal, people have become more aware about the need to build safer, stronger homes. Out of nearly six million buildings in Nepal, one million were affected by the Gorkha Earthquake, which means that the remaining five million buildings need to be strengthened. If left that way, the outcome would be more distressing than the Gorkha Earthquake. More need-based constructions and alternative building practices such as bamboo, improved wattle and daub, wooden and steel constructions could be promoted as per the location, availability, bio-climatic demands and affordability of the occupants.

Housing is undoubtedly a basic need of all, so none should be left behind in having a safe abode. Nepal is overly focussing on earthquake disaster only; however, a large number of houses are damaged by other disasters, such as floods, landslides and fires, among others. Thus, the challenge of building safe settlements cannot be solely based on earthquakes. It is high time Nepal switched to multi-hazard resilience on a local scale. This will definitely bring forth some local yet sustainable and resilient solutions.

Not forgetting the Gorkha Earthquake should be the resolution for now, but considering other natural forces that may bring sufferings to millions of people, building safer should be compulsorily included in planning and implementation initiatives.

Gautam is a researcher in structural earthquake engineering