Distributing humanitarian aid: Necessity of corruption audit

We live in a country where policy makers do not want to strengthen anti-corruption mechanisms but they try to curtail the jurisdiction of such agencies fearing that at some point of time these agencies might actively reveal their corrupt practices

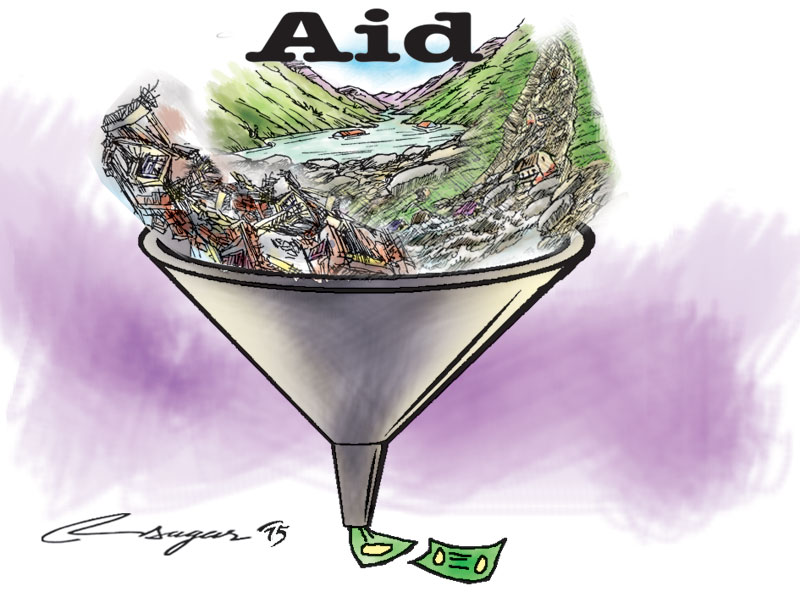

The post disaster research conducted by Integrity International reveals the social disaster that has been unfolded under the banner of humanitarian aid. The money that has trickled down in the name of relief, reconstruction and rehabilitation has been absorbed in large part by a phalanx of NGOs in Nepal bumping chaotically for international grant.

In spite of some upright intent, many of these organizations have channelled money into ill-planned projects with little research, oversight and accountability, leading to waste of aid and profiteering to NGOs that have likely impeded the country’s long-term sustainable development. Many of the countless NGOs that have mushroomed during this post-disaster have haphazardly delivered services without identifying the actual victims and the real needs. The trend of distributing relief and promising reconstruction for mere commercialization was witnessed.

The major complication that may arise when huge sum of humanitarian aid falls into the hands of these NGOs is corruption as the flow of money lacks transparency, accountability and in most part professionalism and dedication. Virtually there is neither any proper way to monitor how these nonprofit organizations operate nor is it easy for the government or the victims to hold them accountable.

Red Cross is considered as one of the most trusted organizations when it comes to relieving pains of the victim and distributing humanitarian aid but there are instances when these trusted organizations do not live up to expectations. In 2013 the Haitian Congress opened an investigation into the Red Cross, prompted by the problems of disaster-related services. The question is who checks any sort of deliberate mismanagement by these organizations as the funds have been flowed in for disaster relief to Nepal.

“Undeniably it is true that the state structures were weak during the disaster and are very weak till date when it comes to vision, planning and implementation of relief and reconstruction,” and there are legitimate reasons for foreign donors to want to bypass the government and trust the private sectors. In the long term, however, Nepal can only develop self-reliance if its public agencies have a stake in the reconstruction since a public body can be made accountable easily in comparison to private sectors. In the light of maximum inflow of foreign aids, the recovery effort might have made more progress by now, had the NGOs and the INGOs prioritized working in coordination with the prevailing institutions rooted in Nepal, “to help the country rebuild its own structure, by stimulating and coordinating and monitoring the government agencies that are already there for these specific reasons.”

The spirit of any humanitarian action is to do no harm. Corruption undermines the basic values of humanitarian action. The crucial supplies, including food, water, medicines and shelter get diverted from affected community and are distributed inequitably and unjustly due to corruption. This in turn has fatal consequences for many victims and the society at large.

Even while conducting internal audits of these organizations the auditors may ‘listen’ to the noise of protests by the public on service delivery and ‘smell’ some sort of corruption but proving it is almost impossible given the scenario where it remains hidden due to perfectly forged documentation and conclusion of the corrupt act in total darkness. This is where I see the necessity of corruption audit—an audit different from the regular official audit rather focuses on the impact of the projects in the society, an audit that is conducted in the field, an audit conducted by the locals.

Enabling Environment for Audit against Corruption requires a multidimensional outbreak. The basic enabling environment at present is integrity, professionalism and transparency along with these sets of strong regulations against corrupt practices, awareness raising campaigns for rights and duties, internal controls, sanctions and motivations, protection of whistleblowers and an open approach towards information reporting. Audit is only one of these mechanisms. The auditors can succeed only if the enabling environment exists unconditionally for fighting corruption. Effective corruption control requires commitment and involvement of all stakeholders and concerned agencies, and in brief, all citizens of the society.

The scope of auditors’ contribution is interlinked with the ‘tone at the top’. If the top executive, in particular, policy makers, a minister or a prime minister of a country engages in corrupt practices, the auditors cannot make effective and efficient contribution as these very persons would not let the auditors get closer to anything as auditing against their corruption.

We have to remember that we live in a country where the policy makers do not aspire to strengthen the anti-corruption mechanisms but they try to curtail the jurisdiction of such agencies fearing that at some point of time these agencies might actively reveal their corrupt practices. In this scenario, we the people need to raise our voice against corruption. We need to unite against corruption before the corrupt politicians and the corrupt system forces us to live a life like Haitians.

The author is President, Integrity International