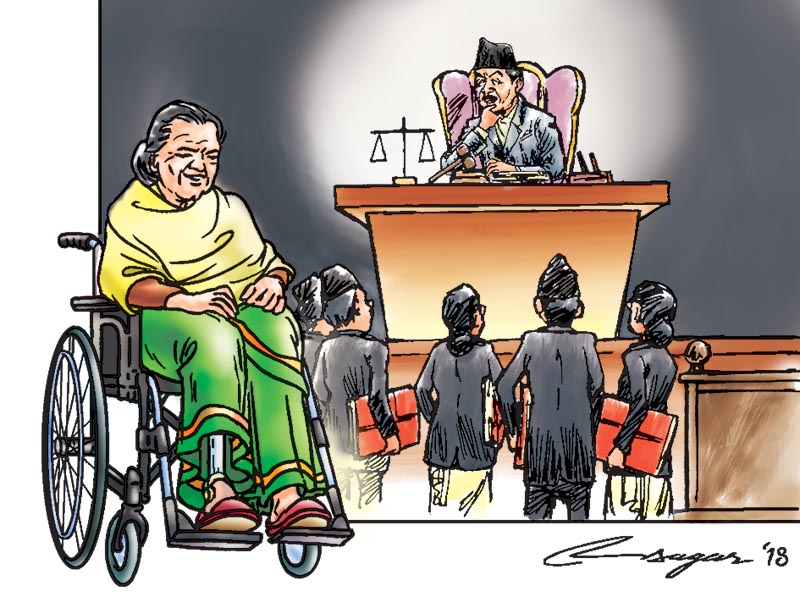

Ensuring access to justice: Women with disabilities face hurdles

Legal barriers, poverty, inadequate information, insufficient resources, inaccessible architectural design, inaccessible communication methods have been preventing women with disabilities from accessing justice

Women and girls with disabilities are at least two to three times more likely to experience violence and abuse than those without disabilities. In addition, they are likely to go through abuse over a longer period of time, resulting in more severe injuries.

Effective access to justice is crucial for ensuring respect, protection and fulfilment of all human rights.

For women and girls with disabilities, inaccessible justice has long been a major cause for concern. For effective social participation, it is imperative that women and girls with disabilities must get equal access to justice. Ensuring justice to women with disabilities can only prevent gender-based violence against them.

Women and girls with disabilities, however, experience disproportionate barriers when it comes to accessing justice due to discrimination and stereotypes that are based on both their gender and disability.

Women and girls with disabilities have been experiencing disproportionate barriers when it comes to accessing justice.

A wide range of barriers operate to prevent women with disabilities from accessing justice. Discrimination and stereotypical mindsets are the first hurdles women with disabilities face when it comes to accessing to justice. Then there are legal barriers, poverty, inadequate information or advice, insufficient resources, inaccessible architectural design, inaccessible information or communication methods, and inadequate protection from subsequent victimisation that obstruct easy access to justice for women with disabilities.

Accessibility of transportation — whether women and girls with disabilities can travel to police stations, courts or other places where justice is administered — also plays a crucial role in ensuring their access to justice.

For ensuring access to justice for women with disabilities, there is also a need of ensuring their right to employment with reasonable accommodation — by creating an environment where they are not discriminated against them for their body or impairment of any sort — in the justice sector. Similarly, there is a need of imparting training for lawyers, judges and law enforcement officials on ways to facilitate justice delivery to women with disabilities.

Some women with disabilities, particularly those with intellectual and psychosocial disabilities, often fail to access justice just on the premise that they have “unsound mind”, which prevents them from testifying in the court of law.

Knowledge about law and rights is also an essential requirement for accessing justice. Women with disabilities often lack knowledge about their rights to and within the justice system because information about their rights is inaccessible, not produced in user-friendly formats and not available in a plain language.

The exact nature of the barriers faced by women with disabilities in accessing justice are likely to differ significantly depending on the type of impairment and intersection between disability and other identities. For example, accounts of violence perpetrated on women with psychosocial and intellectual disabilities in particular are often doubted. Due to this, chances of them being denied justice are high. Also, older people and girls with disabilities from the marginalised community and rural areas are also facing a tough time while accessing justice.

In addition, many professionals in the justice and service provision sectors hold misperceptions and stereotyped views about women with disabilities and their rights under the law.

Poverty is yet another barrier for women with disabilities when it comes to accessing justice. In many developing countries like Nepal, women with disabilities living in rural areas are more likely to live in poverty than men with disabilities or non-disabled women. As a result, women with disabilities often cannot afford court costs.

The United Nations Convention for the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) recognises that without access to justice, there is no remedy for women to address gender-based violence.

Article 13 of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) is, in short, an innovative provision in an innovative treaty which, taken as a whole has the potential to operate as a powerful lever for improving access to justice for disabled people worldwide and for inspiring analogous developments in the context of other marginalised groups.

The constitution of Nepal has created space to ensure access to justice for all and the provision has captured the spirit of the CRPD. Currently, Nepal is in the process of state restructuring and the new laws and policies are being developed. This is an opportunity to materialise “access to justice” for the persons with disabilities in line with the CRPD. However, the existing laws, policies, judicial institutions, and knowledge, skill, capacity and attitude of persons engaged in justice mechanism are unable to close the gap between theory and practice. This also has kept persons with disabilities far from justice.

Access to justice for women with disabilities not only requires that police and courts are available for them, but also that these arenas are fully accessible and inclusive.

Joshi is a disability rights lawyer