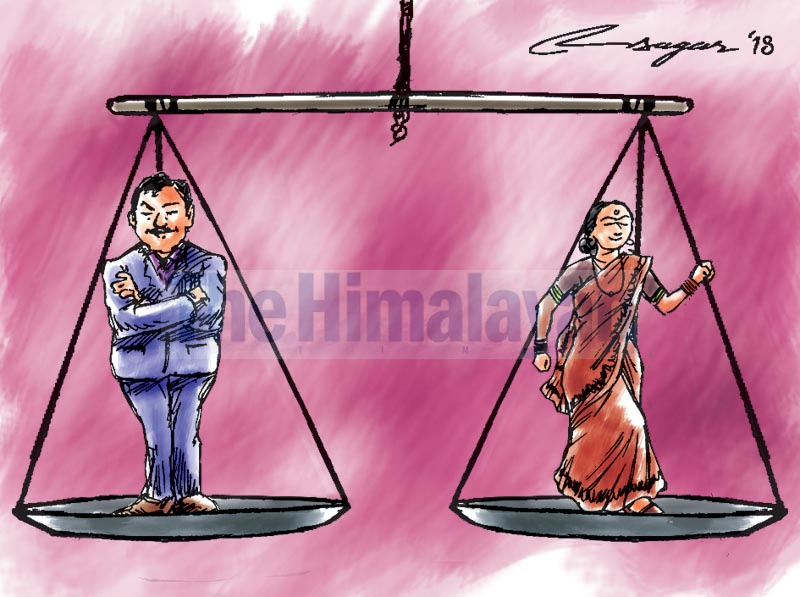

Gender equality: Key to healthy ageing

Both governments and civil society must address the complex demographic shift of population ageing with strategic solutions and programmes. To do so successfully, we need a life-cycle approach to healthy ageing, with particular emphasis on girls and women, firmly grounded in gender equality and human rights

In a relatively short time, COVID-19 has devastated the lives of millions globally.

For hundreds of millions more, the toll wrought by the pandemic could have lasting effects for decades.

Perhaps one of the most cunning aspects of this virus is the harm it inflicts on older persons who face multiple and compounding threats, including being physically more vulnerable; at greater peril of the impacts of social isolation; and at significant risk from the grave and likely long-lasting socioeconomic shocks of the pandemic.

COVID-19 has proven to be acutely dangerous for people with underlying health conditions, ranging from diabetes and asthma to cardiac disease and cancer.

A disproportionate death rate is seen amongst older persons in most countries. Beyond physical health, the pandemic continues to take a heavy toll on older persons — and women in particular — in terms of psychosocial health and economic well-being.

In the Asia-Pacific region, these impacts are particularly acute, adding to the existing challenges of grappling with accelerating population ageing. This region is currently home to over half the world’s population over 60 years of age.

Globally, the number of older persons is expected to surpass 2 billion by 2050.

By then, nearly two-thirds of the world’s older people — close to 1.3 billion — will be in Asia-Pacific, with one in four people over age 60.

Women, who generally outlive men, currently constitute the majority — some 54 per cent — of older persons in Asia-Pacific, but represent an even greater majority, 61 per cent, of the ‘oldest old’ population of 80 years and over.

Even before the COV- ID-19 crisis, elderly women in a majority of Asia-Pacific countries were facing significant challenges, exacerbated by the fact that many societies have been moving from traditional, nuclear family-oriented patterns to far more fluid, fragmented structures. The result has been that many older women, with a higher tendency to live alone, face poverty and are more likely to lack family and other socioeconomic support.

The majority of older people do not have reliable and sustained access to a caregiver. Facing non-existent or only minimal safety nets, many have already slid into poverty during the pandemic or are on the cusp of doing so.

The pandemic has brought into acute focus the urgent need for both governments and civil society to address the complex demographic shift of population ageing with strategic solutions and programmes.

To do so successfully, we need a life-cycle approach to healthy ageing, with particular emphasis on girls and women, firmly grounded in gender equality and human rights.

To unpack this, let us consider a woman in her 70s in the small village where she was born and raised.

As with so many of her generation, she was made to marry early, with minimum education. She had children early, pregnancies were unplanned, childbirth was risky. Her husband, many years older, died a long while ago, leaving her a widow, unprepared to enter the workforce or properly fend for herself. Her children left the village for the city, adding to her isolation.

This is the scenario many older women now face – with the added risks, burdens and effects of COVID-19.

But imagine if, as an adolescent, this woman had been able to take that other branch of the road: completing school and higher education; achieving gainful employment; marrying as an adult and of her own choice; having healthy children and being able to invest in their well-being; and, ultimately, enjoying a secure old age.

If addressed in a holistic way and underpinned by better policies, more resilient social systems and gender equality, the lives of older people, especially women, can be improved significantly. This would also allow societies to harness the valuable experience and knowledge of older persons as they age - reaping a ‘longevity dividend’ from healthy, active older people who can continue their engagement in family and community.

In fact, the commitment to advance a better world in an ageing society has already been articulated by the 2002 Madrid International Plan of Action on Ageing. This agreement commends the development of evidence-based policies that help create ‘a society for all ages’. In addition, the landmark Programme of Action of the International Conference on Population on Development (ICPD), as well as the 2030 Agenda and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) underscore the basis of this approach to healthy ageing.

We must collectively now prioritise greater action, funding and implementation.

Within UNFPA, our mandate clearly incorporates the need to enable and strengthen the self-reliance of older persons including women, enabling their participation for the benefit of both society and themselves.

The ICPD Programme of Action is our foundation, and our guiding principle.

As the United Nations Population Fund, the UN’s sexual and reproductive health agency, we are increasingly seeing countries turning to us for advice and assistance on issues of population ageing. UNFPA is committed to helping governments in full partnership with civil society and communities.

2020 launches the Decade of Healthy Ageing as well as the Decade of Action to achieve the SDGs.

As Asia-Pacific, with the rest of the world, seeks to ‘build back better’ from the devastating effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, let us seize this moment to transform the challenge of population ageing into opportunity.

We must translate gender equality and human rights into practical strategies and approaches that ensure no older woman will ever be left behind.

Andersson is the United Nations Population Fund Regional Director for Asia and the Pacific. October 1 marks the International Day of Older Persons