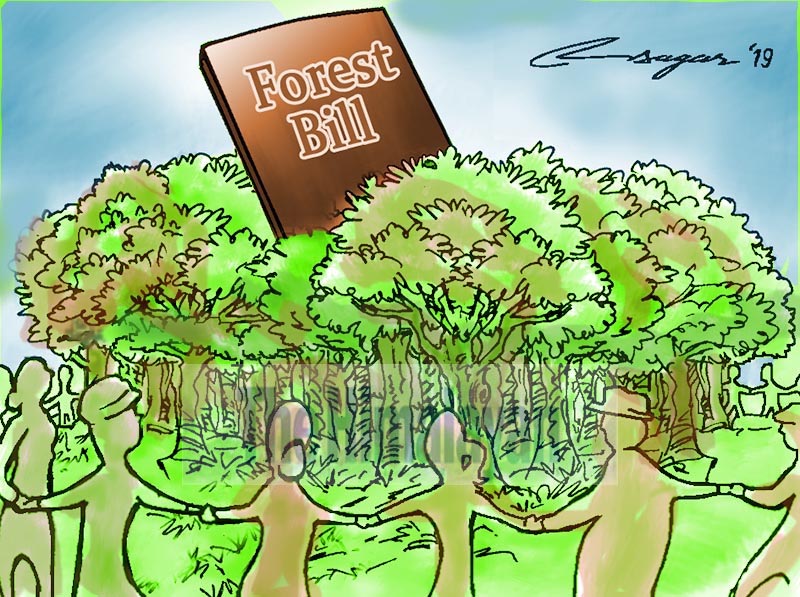

New Forest Bill: Opportunity for transformation

Collaboration among stakeholders has always been the key to the success of the Nepali forestry sector, no matter what the management objectives. We can succeed by making forestry the business of everyone, not of a selected few

Nepal’s forestry sector is in the limelight once again. The Federal Parliament has forwarded the new Forest Bill to its Environment Protection Committee for discussion. The Bill is contentious in that the forest stakeholders, with strong representation from the local communities, have voiced concern, saying the Bill fails to adequately situate forest governance within our changed political and socio-economic context.

Stakeholder concerns are casting a shadow on some of the Bill’s positive provisions. The Bill is progressive in allowing ecotourism in the community forests. It recognises the need for more support to the community forest user groups, organised to manage forests. It allows them to punish non-cooperating offenders of rules they set collectively. The 1993 Forest Act lacked these progressive provisions.

But the stakeholders say the Bill limits their rights to manage and draw fair benefits from the forests, in which communities have invested heavily over the decades because they believed this would generate benefits forever. They say the Bill reduces the autonomy of the community forest user groups, which engage nearly half of Nepal’s population in managing more than a third of the countries forest area—more than 2.2 million

hectares.

Communities say they will lose their right to freely determine the price of the forest products they sell. Another concern is the Bill would enable the government to take back the forest from the user groups if they fail to comply by a mutually agreed forest management plan.

Some stakeholders oppose how the Bill positions the federal government to retain significant control over community forest management through the Division Forest Officer while limiting control and support by the provincial and local governments, contradicting the intent of the 2015 Constitution.

Forest communities see these and some other provisions in the Bill as a betrayal of their trust and a failure to meet the aspirations of people-centred management of natural resources envisioned in the new constitution.

As builders of capacity for people-centred forestry, we at the Centre for People and Forests (RECOFTC) want to highlight challenges in forest governance. Our 2016 study of community forest management in Nepal found that the process of formalising and exercising their rights to manage and benefit from the forests was too complex and costly for many communities. For this reason, nearly one-third of the community forest user groups were unable to renew their operational plans. And many became legally dysfunctional.

Our study also found that a lack of legal support for collaboration among the user groups was a major barrier to running community forest-based enterprises and accessing financial resources. Collaboration among groups is necessary because one forest user group often does not have sufficient supply of a product to support a viable enterprise or the ability to reach markets.

The concern for the Bill is set within a larger context—that of the global climate emergency. The effects are highly visible in the Chure range where deforestation and forest degradation are exposing millions of people in that area and downstream Tarai to natural disasters and water scarcity. As we consider the Bill, we need to reflect on the role our forests play in mitigating and adapting to climate change.

Through Nepal’s Nationally Determined Contributions, agreed in the 2015 Paris Agreement, we committed to addressing climate change. The NDCs aim to increase forest productivity and sequester more carbon, while improving forest governance. A recent study proves that community forestry in Nepal is helping us achieve 80 of 169 Sustainable Development Goals.

The Bill can’t address all the issues faced by the forestry sector, but it can lay the foundation for transformation. By bringing together the stakeholders to discuss these issues, we can envision a desired future for our forest sector.

As we improve the Bill, now is the time to consider whether the organisational structures created for command and control styles of management decades ago can be changed to provide more support and fair benefits for communities. Now is the time to discuss how community forestry can become self-sustaining in Nepal and how it can provide more jobs, tangible economic benefits for people and reduce timber imports, which capture half the domestic market.

To make these improvements, we need only three things to succeed: open minds, balanced power relationships among forestry stakeholders, and a willingness to listen, understand and address other stakeholders’ concerns.

The message is clear. Collaboration among stakeholders has always been the key to the success of the Nepali forestry sector, no matter what the management objectives. We can succeed by making forestry the business of everyone, not of a selected few. The success of those in power will be measured by the extent to which they open spaces for stakeholder collaboration in achieving the vision of ‘Forestry for Prosperity.’

As we face the climate emergency together, we must act in the interest of future generations. We must take bold steps to secure our forests, not only for the well-being of Nepal, but for the world.