People with disabilities: Access to justice

Substantive access to justice for disabled people can be achieved only by facilitating their entry into, and full participation in, the legal professions, the legislature and other public offices; and by involving disability rights lawyers in the design and delivery of laws, policies and services

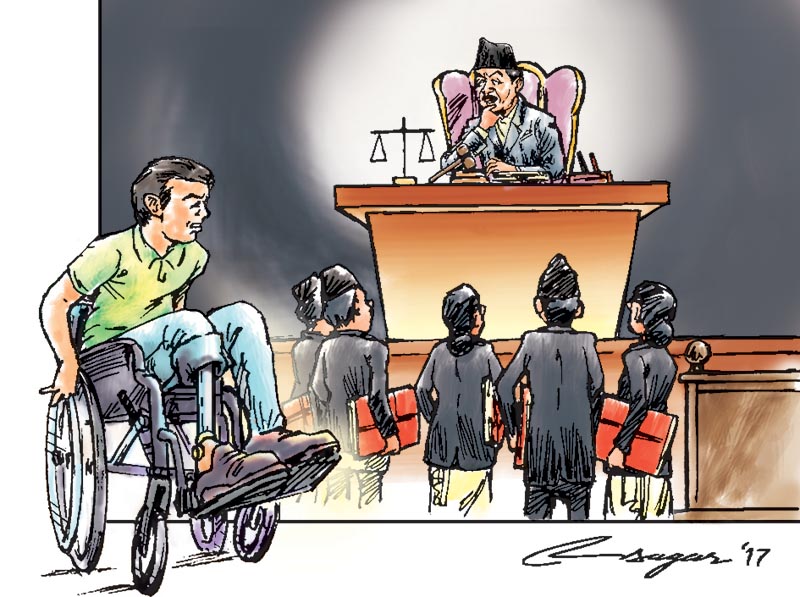

Access to justice for persons with disabilities includes being treated equally and having access to general court services. It also means having full access to the environment of a court, which may include providing physical access or interpretation services. A wide range of barriers operate to prevent disabled people accessing justice on an equal basis with others.

These include barriers in the form of laws denying them legal standing; inadequate information or advice; insufficient resources; inaccessible architectural design; inaccessible information or communication methods. Of all the barriers facing disabled people in accessing justice, perhaps the most prominent are those created by plenary and partial guardianship laws which disproportionately affect people perceived to have disabilities, especially persons with intellectual disabilities.

In Nepalese context, persons with disabilities (people with psycho-social disabilities, intellectual disabilities, deaf and persons with visual impairment) are incapable of legal exercise. Nepal’s ratification of Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) in 2010 did not bring any significant positive changes of existing laws that are against the principles and provisions to exercise legal capacity on an equal basis with others. Persons with disabilities are often victims of crime, or serve as witnesses in criminal proceedings.

Therefore, they may be required to participate in criminal proceedings including police investigations and criminal trials. However, their interaction with or participation in the criminal justice system does not always occur on an equal footing with their non-disabled counterparts. Persons with disabilities often face numerous barriers to effectively fulfilling their role as witnesses in the criminal justice system. This is often the result of the interaction between a particular limitation related to disability and an unresponsive criminal justice process which fails to take into account the impact of disability. One type of barrier is the inaccessibility of the environment—for example where a person with a physical disability is not able to access the building where the courtrooms are housed. But a whole other type of barriers relates to the inaccessibility of the procedures.

These barriers may be overcome through the use of appropriate accommodation. The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities defines reasonable accommodation as “necessary and appropriate modifications and adjustments … where needed in a particular case, to ensure to persons with disabilities the enjoyment or exercise on an equal basis with others of all human rights and fundamental freedoms.” Accommodation is intended to enable persons with disabilities to participate in the criminal justice system on an equal basis with others. They are not intended to relax the rules of criminal evidence and procedure for persons with disabilities, but simply to level the playing field and allow persons with disabilities to effectively participate in criminal proceedings on an equal basis with others. The use of accommodation allows persons with disabilities to effectively tell their story, whilst still maintaining the gentle balance between witness participation and the right of an accused person to a fair trial, the trademark of the criminal justice system. It is vital to ensure that the accused person’s right to a fair trial is upheld and the provision of accommodation for complainants and witnesses with disabilities does not interfere with this right.

For example, cross-examination of a witness with disability cannot simply be done away with because it is difficult for that person. Rather, accommodation should ensure that a witness with disability is not more affected by this kind of examination.

There should be experts who can provide such accommodation. The experts should be aware and respectful of the legal process. In particular, they must take care not to pollute any evidence. It is generally accepted that the more someone tells their story, especially if this happens not in the presence of a police investigator, the greater the question mark over whether that ad hoc investigation without the presence of an investigator follows the rules of not leading the person investigated. In the event that the complainant meets the accommodation supporter before reporting to the police, the accommodation supporter should refrain from asking the complainant to tell their story right away, but rather refer the complainant to a police station, where the complainant can then give their account (with the supporter’s assistance in making accommodation, as relevant). It is logical that if someone needs accommodation at the police station stage, that person will also need accommodation in court. Thus, the accommodation supporter has a similar role in court—to provide an equal opportunity to witnesses with disabilities to have their day in court without being more adversely affected because of their disability.

Substantive access to justice for disabled people can be achieved only by facilitating their entry into, and full participation in, the legal professions, the legislature and other public offices; and by involving disability rights lawyers in the design and delivery of laws, policies and services.

Joshi is a disability rights lawyer