Quest for smart cities: Learn from ancient towns

Nepal should learn from its own ancient cities such as Kirtipur, Bungmati, Lubhu and Khokna in the Valley and other hilltop towns such as Bandipur and Doti as well as some ethnic settlements in the Tarai, including the Tharu settlements

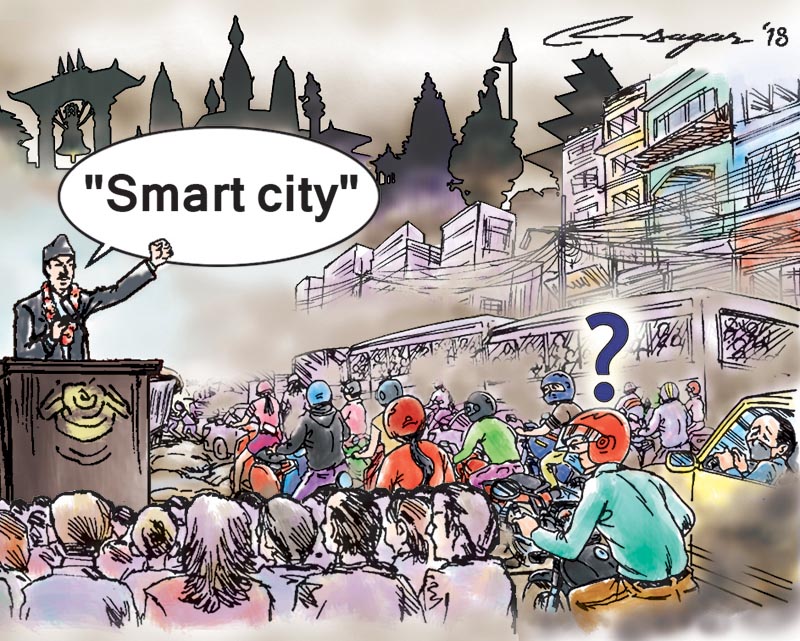

Smart cities have become the buzzword of late. Smart cities, as a matter of fact, had become the main agenda of almost all the parties of different hues during the recent elections held last year.

The term “smart city” seems to have cast a spell on many newly elected mayors, as they have made it their priority agenda for their tenure.

But what are smart cities? Different people may have different opinions – just like people make different views about the paining of Mona Lisa, which they find either happy or sad |depending upon their mood.

So for some, a city becomes a smart city if it takes a dip into the pool of science and technology, especially Information and Communication Technology. And others opine that the aforementioned definition is insufficient and that a smart city, in essence, is much more than this. The fact of the matter is there is no universally

accepted definition of a smart city.

Smart as a word that we use to qualify cities today first emerged from what was called smart growth, of which Portland, Oregon is taken as a glaring example. It then spilled into naming of electronic gadgets – as we call our phones smart phones today. This name then spread into the urban world labelling the cities as smart. In this respect, China, Japan and Korea led the way. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi also promoted this concept announcing a programme of 100 smart cities.

“Smart cities” is something that has become a household term not only in Nepal but across the globe.

KT Ravindran, Professor Emeritus of School of Planning and Architecture, Delhi says “our traditional smart cities display a compact form, optimum density, and sustainable material and social infrastructure; they were the smart cities of their times.”

A smart city is also portrayed as a six-headed entity consisting of smart energy, smart environment, smart governance, smart people, smart mobility and smart economy.

If we look at the semantic history of the word smart, it has changed its meaning many times.

According to the Oxford Dictionary, “smart” as an English word first appears to have been used in the year 895, which then meant a severe wound.

Little later by 1023, it meant a rod that was used for whipping. If we correspond this time with our history, the period belongs to the Thakuri Dynasty which is known as the dark period in Nepal in view of paucity of information available compared to its predecessor Licchavi Dynasty which had reached dizzying heights of progress and prosperity as described in innumerable inscriptions of this period.

It is no wonder that period is known as the golden era of Nepal.

They used Vedic city forms such as Sarbhatobhadra, Dandaka, Padmaka, Swastika, Prastara and Karmukha among others.

Prastara is said to have been used for Hadigaon, the Lichhavi capital city. Rajbiraj was designed following Prastara form after its designer Dilli Jung Thapa went to see a similarly formed Jaipur, which is known as the “pink city” of India.

The Licchavi and the following medieval and Malla cities reflected almost all the attributes of a smart city. They were compact as they had a human habitation in the elevated area with the peripheral low area left out for agriculture. The density was optimum, as a satellite city was created once the mother city exceeded a population of 10,000. Since there was no vehicular menace then, these cities were designed keeping pedestrians in mind. The roadsides worked as “open supermarkets”.

There were socially sustainable networks like Guthis. The buildings had mixed use – they were used for accommodation as well as for working space. The materials used consumed very low energy. It can thus be concluded that Nepal was already bestowed with smart cities before the word smart meant something else; not what it means today.

It is so because it was only in the 17th century, in the year 1628 to be precise, the meaning of smart changed to “clever” – the way we understand now.

When we talk about smart cities, Nepal hence has virtually become a musk deer frantically searching for the perfume somewhere around not knowing that its very source is within itself. Nepal thus should look back into its own cities such as Kirtipur, Bungmati, Lubhu and Khokna in the Valley and other hilltop towns like Bandipur and Doti as well as some other ethnic settlements in the Tarai, including the Tharu settlements.

That said, their simple imitation is not enough, as it would be a mere pastiche.

So efforts should be made to incorporate some modern aspects related to Information and Communication Technology while building smart cities while we take some lessons from our historical cities.

These may consist among others the use of digital sensors and control systems for the control and operation of urban infrastructure.

At household levels, cooking can be remotely controlled though the use of smart sensors. It will simplify the complications inherent in the society that we live in.

This will also lead to the formulation of smart cities with a difference – smart cities brimming with identity and the spirit of the place.

Pokharel is vice-chancellor of Nepal Academy of Science and Technology