Restructure SSDP: In line with federalism

Nepal will only achieve its 2030 vision of ensuring equitable access to safe and quality education for all if the education sector plan and objectives are owned across all governments at the local, provincial and federal level

The School Sector Development Plan (SSDP) is a seven-year programme for fiscal years 2016/17 to 2022/23. It is the overarching strategic plan for the education sector and is designed to achieve the goals and objectives of the national periodic development plan and Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 4 of ensuring equitable access to quality education and life-long learning for all. The SSDP is implemented through a five-year cost programme (2016-2021), which is jointly funded by the Government of Nepal and nine joint financing partners (the Asian Development Bank, the European Union, Finland, the Global Partnership for Education, JICA, Norway, UNICEF, USAID and the World Bank).

The development partners support the SSDP programme through a Sector Wide Approach (SWA) modality, which entails development partners agreeing on joint indicators and reviews that trigger disbursement. This allows for both types of development partners, ones that use result-based financing instruments (the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank and partly the European Union) and those that support through programme-based support. The vast majority of the support (80 per cent) is result-based financing and as such is based on the achievement of annual disbursement-linked indicators (DLIs). The remaining 20 per cent of the official development assistance is provided through an overall satisfactory progress against the SSDP results framework targets.

The SSDP can be looked and described through multi-angles. The government accepts it as a plan and programme whereas the financing partners consider it as a project. It is also taken as a programme framework, which can give space for other potential development partners under its broader framework with a view to fulfilling the much-needed financing gaps. It also includes the joint programming and reviewing mechanism as characterised in a project-based approach to engage the development a.

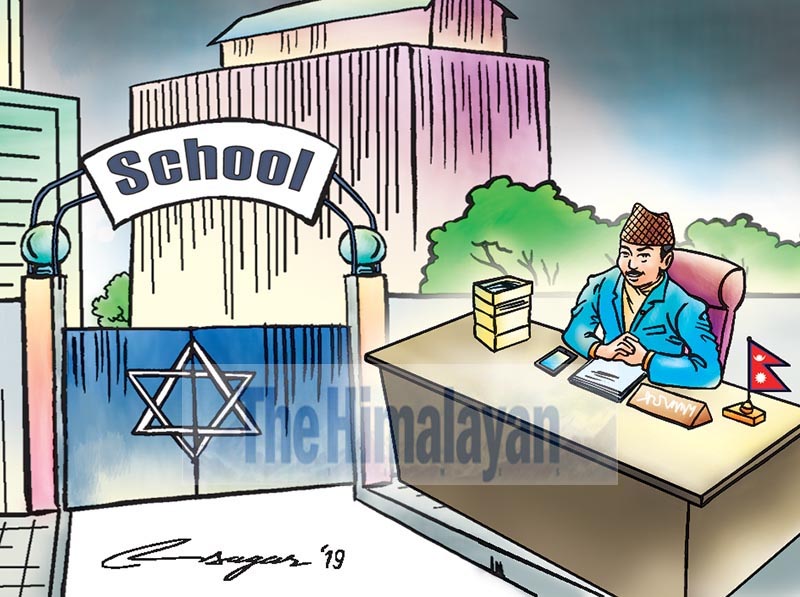

As the SSDP was initiated in July 2016, it was designed before the introduction of the new federal governance structure that has been rolled out. With the new constitution assigning governance authority and functions among the federal, provincial and local governments, the institutional restructuring has downsized central level institutions, created new administrative set-ups and assigned considerable governance and fiscal authority to the provincial and local levels. The management and control of school education has been reassigned, mainly to local levels. The fact that the SSDP was designed to achieve its goal and objectives under the old unitary governance system raises question of ownership of the plan and its programme by the new local governments.

This leaves the federal government and education sector development partners facing some major questions during the remaining SSDP implementation period. Under the new federal system, local governments are responsible for implementing the SSDP activities, but were not in place while designing the programme and, therefore, are likely to feel little ownership of the SSDP. Furthermore, given the high levels of autonomous mandate provided by the constitution, the local levels are not under the direct control of the federal ministry. The question of whether the local levels remain responsible to report progress against the centrally defined targets has been raised.

Another major question is whether a central SWA modality and joint financing arrangement remains a valid modality in a highly decentralised governance and funding structure. Local levels have substantial flexibility to allocate their budget across sectors, and as such, the education sector budget is no longer decided and allocated based on a centrally developed budget alone. This poses a problem for the development partners that need assurances that the provided funds are utilised for intended purposes.

In response to this, the SSDP budget has been allocated in the current and previous fiscal year through federal conditional grants to the local governments. Although this is an understandable measure for the short or transitional term to prevent interruption of major strategies and services within the school education sector, this can be easily seen in the longer term as not allowing the local levels to plan, budget and implement their local plans in line with their constitutional mandate.

In conclusion, there is an urgent need to take the SSDP goal, objectives, targets and strategies to the local levels and ensure meaningful review and validation at this level. Based on this, there needs to be a genuine effort to identify the scope, structure, implementation arrangements and ownership of the plan, ensuring full alignment with the decentralised context and full alignment with Nepal’s long-term vision and plans and international commitments.

As part of this, Nepal will also need to define how development assistance can and should be utilised to support education reforms in a federal context.

Nepal will only achieve its 2030 vision of ensuring equitable access to safe and quality education for all if the education sector plan and objectives are owned across all governments at the local, provincial and federal level.

Lamsal is Joint Secretary, Ministry of Education, Science and Technology