Scaling up nutrition: Need for multi-sector approach

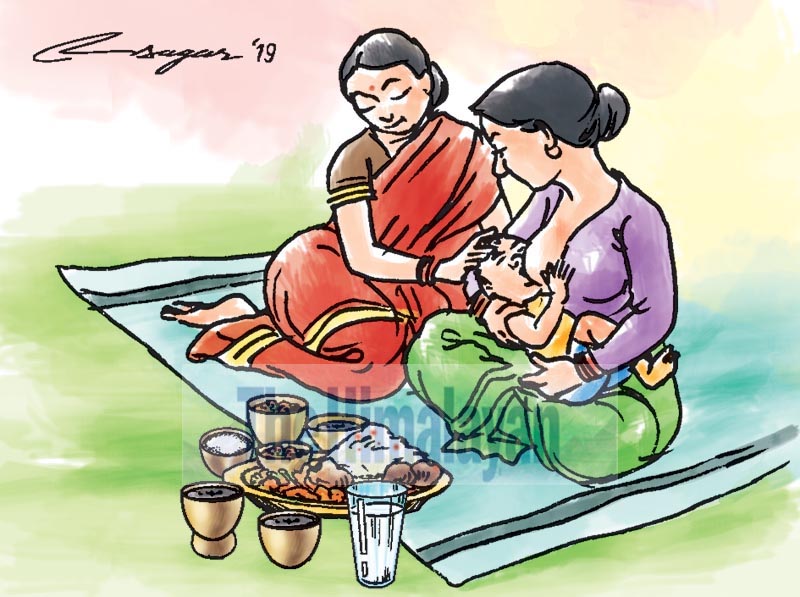

The first 1,000 days from a woman’s pregnancy to a child’s second birthday is an opportunity to prevent malnutrition and its consequences. We must, therefore, support breastfeeding and provide micro-nutrient supplements for women and children

Malnutrition is alarmingly high in most developing countries. According to Global Nutrition Report 2018, children under five years of age face multiple burdens: 150.8 million are stunted, 50.5 million are wasted and 38.3 million are overweight. Meanwhile, 20 million babies are born underweight each year.

Malnutrition is particularly severe in Nepal. According to the National Planning Commission (NPC), about 36 per cent of Nepal’s children suffer from stunting, 10 per cent from wasting and almost 53 per cent from anaemia. There is considerable room for progress as the current stunting rate is still unacceptably high. Moreover, 66 per cent of children aged 0-5 months are exclusively breastfed. Only 47 per cent of the children aged 6-23 months are receiving diversified diets and 36 per cent of them receive a minimum acceptable diet.

While Nepal targets to reduce the rate of stunting from 36 per cent to 24 per cent by the year 2025 and 14 per cent by 2030, more strategic investments are needed to enhance the capacity of local governments in strengthening the health systems and nutrition-sensitive agriculture practices in the rural areas. This is crucial to ensure improved and equitable access to nutritious diets and care for all children, including adolescent girls, and women of reproductive age.

Investments in nutrition, particularly in the earliest years of life, can yield significant results for children, their families and communities. Despite some concerted efforts, progress is still slow in reducing the burden of malnutrition. In order to address the complex challenges of malnutrition, Nepal has made some progress in terms of policy and strategic interventions in the area of nutrition and food security. In this context, National Nutrition Policy was first developed in 2004.

Nepal joining the Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN) Movement in 2011 was one of the steps in the right direction. In most SUN events globally, Nepal’s participation is appreciated in terms of enhanced political commitment, resource mobilisation and multi-sector approach in scaling up nutrition across the country.

This year, SUN Global Gathering will convene in Kathmandu from November 4 to 7, which will bring all SUN government focal points and representatives of their partners from the civil society, development partners, UN agencies, private sector, academia, media, parliamentarians and others. This event specifically aims to take stock of the progress and challenges and share their innovations and experiences to reduce malnutrition across all SUN countries.

In 2011, the Nutrition Assessment and Gap Analysis (NAGA) was conducted to identify the primary determinants of malnutrition in Nepal. These mainly included inadequate food availability; access and

affordability; poor food and care-related behaviours; inadequate food quality and nutrient density; and high prevalence of infections. This led to the formulation of the first ever Multi-Sector Nutrition Plan (MSNP) (2013 –2017) in the country with lead support from UNICEF and all partners.

MSNP aims to increase access to and the use of nutrition-sensitive services at all levels. The health, education, water and sanitation, agriculture and livestock, local governance, women, children and social welfare sectors have an important role to play in improving the nutrition status of children, adolescents and women across the country.

The first 1,000 days from the start of a woman’s pregnancy to a child’s second birthday is an important window of opportunity to prevent malnutrition and its consequences. Therefore, we need to scale up evidence-based interventions, including support for breastfeeding, appropriate complementary foods for infants over six months, and micro-nutrient supplementation for women and children.

More importantly, there is a crucial need to provide technical support to the National Nutrition and Food Security Secretariat (NNFSS) at the NPC for effective planning and implementation of the MSNP through sectoral ministries and departments at all levels. In order to facilitate coordination and mainstreaming of nutrition-sensitive interventions across sectors, capacity building of the federal, provincial and local governments should be the first and foremost priority of the NNFSS.

On the other hand, there are challenges and opportunities to ensure that the periodic and annual plans of the local governments as well as federal ministries sufficiently integrate nutrition and food security interventions in line with the MSNP and the Food and Nutrition Security Plan (FNSP).

Apart from this, the increasing role of civil society, the private sector and academia has been instrumental in reaching out to the local communities in creating awareness, advocacy and capacity building of the local stakeholders in the area of nutrition and food security.

To sum up, a new roadmap is needed to facilitate coordination and implementation of the MSNP at large. Tracking the progress of MSNP interventions and generating sufficient evidence regarding its outcomes, impacts and sustainability is a challenging task. The plan targets children, women and adolescents and aims to make crucial contributions to achieve the SDGs by 2030.

Bhandari is a PhD candidate in public health at Chulalongkorn University, Thailand