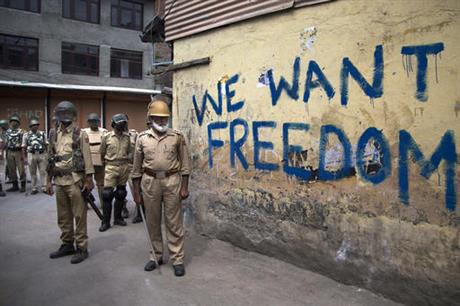

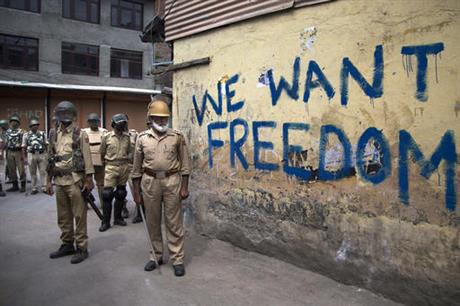

Police face public wrath amid anti-India uprising in Kashmir

SRINAGAR: Before the crack of dawn and before the protesters hit the streets to resume demands India leave Kashmir, he dressed like an ordinary man and made sure not to carry anything identifying him as police.

He joined six passengers in a shared taxi outside his village in a lush pine forest near the militarized boundary that divides the Himalayan region between India and Pakistan. A young woman asked if he was a policeman, warning that it could mean trouble for all of them if he was found out by the anti-India protesters who regularly check IDs at highway roadblocks.

"I couldn't lie," the officer said. He managed to convince them he could pass undetected. "But deep down I was shattered, and scared, given how hard it is to hide one's identity in this place."

As Kashmir enters a third month of tense conflict marked by violent street clashes and almost daily protests, Indian government troops backed by local police are maintaining a tight security lockdown throughout the region.

That's left the local Kashmiri police, tasked with patrolling the streets, gathering intelligence and profiling anti-India activists, feeling demoralized, afraid and caught in the middle between the Indian authorities who employ them and the friends and neighbors who question their loyalties.

The plainclothes officer in the taxi — one of 12 police officials who spoke with the Associated Press on condition of anonymity for fear of both public reprisal and official retribution — managed to avoid detection until he reached his precinct in the main city of Srinagar.

But a few days later, he said, his colleague wasn't so lucky. He was slapped and beaten, his clothing torn, at one of the protesters' ad-hoc checkpoints, "let go only after some elders intervened."

Many of Kashmir's 100,000 or so police officers say they are facing increasing suspicion by locals since the July 8 killing of charismatic rebel leader Burhan Wani by Indian government forces sparked the latest unrest.

An ongoing curfew, a series of communication blackouts and the deployment of tens of thousands of Indian soldiers has so far failed to stop the protests against Indian rule. More than 70 civilians have been killed and thousands wounded, mostly by government forces firing bullets and shotgun pellets. Two local policemen have also been killed and hundreds other injured during the clashes.

In recent weeks, Kashmir's separatist leaders have begun calling the police out — naming individuals as having betrayed the Kashmiri community. When one officer was publicly accused of firing a shotgun at a protest rally last month, his family showed up at the home of separatist leader Syed Ali Geelani and pleaded for forgiveness.

The family of another officer accused of fatally shooting a protester fled their Srinagar home after it was covered with graffiti reading "Killer" along with the officer's name.

Police stations are being attacked with stones and gasoline bombs. At least a dozen stations have been damaged, including four burnt down. Officers' families are facing harassment including public jeering and verbal abuse.

"We get panic calls from our families about our well-being," said a senior police official who commands some 4,000 officers in the region. "The situation is quite grim, and we're caught between the devil and the deep sea. It takes a lot of effort to keep my men motivated."

More than 20 have seen their own sons detained for participating in anti-India protests, according to a senior officer who said he facilitated their release.

"Orders flow from the top, from Indian officers who have no stakes here," the officer said. "We're just earning a living. We are hostages to our livelihood."

For some, the stress of being in a position deemed traitorous has proven to be too much. At least two counterinsurgency cops have resigned in recent weeks. One of them, Waseem Ahmed, said he was afraid for his family in the southern town of Sopore after local protesters had gathered outside their home. A video showing Ahmed apologizing to the crowd and chanting the slogan "We want freedom" along with them has gone viral.

The discomfort Kashmiri police face in their work has existed to some extent since the late 1940s, when India and Pakistan won independence from the British empire and began fighting over rival claims to the Muslim-majority region.

Many Kashmiris on the India-controlled side see local police as tools of an Indian government bent on suppressing a widespread public demand for the region's independence or merger with neighboring Pakistan.

In the 1950s and 60s, police routinely detained people for listening to Radio Pakistan. Later, they worked to scuttle anti-India political movements and break up armed rebellions by infiltrating their ranks and locking up agitators.

When the latest armed insurgency erupted in 1989, police initially fought against it. Within a few years, as rebels began targeting their families, many abandoned the task and stayed at their posts and barracks. Some also began sympathizing with and supporting the rebel demands as the campaign morphed into a full-fledged rebellion backed by massive public support. Dozens even joined the rebel ranks, rising to become militant commanders including one of Wani's close lieutenants — former police constable Naseer Pandit, killed in a gunbattle in April.

The Indian army deployed a special contingent along with tanks to Srinagar in 1993 to quash a so-called "police mutiny," ending with the arrest of hundreds of officers.

But two years later, India formed a new counterinsurgency police called the Special Operations Group, drawing most of its members from among Kashmiri police officials from the highly militarized and remote mountain regions near the de-facto border with Pakistan. The dreaded force has been widely accused by Kashmiris and human rights groups of some of the worst violations reported during the last two decades of conflict, from summary executions, torture and rape to holding suspects as well as civilians for ransom.

Still, the legacy of the Special Operations Group is something Kashmiris find hard to forgive. And deep grudges have turned into open hostilities, especially during public uprisings against Indian rule.

"They are traitors and suppress their own brethren to win rewards and promotions from their masters," said a civilian man who would only give his middle name, Nabi, for fear of police reprisals. "The police have turned into India's cutting-edge weapon against Kashmiris. They are their eyes and ears on the ground."

Meanwhile, the size of Kashmir's police department has swelled from just 18,000 officials in early 1990s to more than 100,000 today. And despite public suspicion, many eagerly joined for the steady paycheck in a region beset by high unemployment.

The police force says it is carrying out its duties and working to keep Kashmir safe. That has included launching raids in residential neighborhoods in hunting down rebels, ransacking homes and even beating protesters who are out of line.

The harassment "doesn't deter us from doing our job," said the region's top officer, Syed Javaid Mujtaba Gillani. "We'll do what we have to do."

Some say their job is to keep the situation from getting worse, and to keep more protesters from getting killed.

"We act as a buffer. Otherwise these (paramilitary) men will end up shooting dozens in an average protest," one officer said, pointing to Indian soldiers on patrol in front of a shuttered storefront painted with the words "Go India, Go Back."

But another working beside him last week, enforcing a nighttime curfew in Srinagar, said that no matter what good they do, they are still being exploited by India and punished at home.

"A police job means pitting one Kashmiri against another," said another policeman. "At the end of the day, a Kashmiri policeman is also a hostage of the occupation."