Mount Vernon exhibit looks at Washington as slaveholder

MOUNT VERNON, VIRGINIA: It is the unavoidable Achilles' heel in the reputation of George Washington and so many other Founding Fathers: that men who risked their lives to protect their nation's liberty were also slaveholders.

That dichotomy will be explored in a new exhibit at Washington's Mount Vernon estate, in a museum space previously dedicated to exhibitions featuring Washington's furniture, fineries and his penchant for dining on syrupy hoecakes.

The $750,000 exhibition, Lives Bound Together, will explore hard truths about Washington's life as a slaveholder, including an acknowledgement that Washington's adopted son likely fathered a child with one of the family's slaves.

Mount Vernon has not shied away from explorations of slavery: In 2007, the estate reconstructed a slave cabin on the grounds about a mile from the iconic mansion. And Mount Vernon has worked to maintain good relations with the descendants of Mount Vernon slaves, many of whom still live in the area.

Still, Mount Vernon director Curtis Viebranz said he occasionally hears criticism — both from people who believe there is too much discussion of slavery, to those who say they won't visit Mount Vernon because they are offended at supporting what was, at bottom, a plantation fueled by slave labor.

He expects the new exhibit will inevitably draw criticism in one form or another.

"There might be some people of my generation who would prefer to leave him on his pedestal," Viebranz said. "Our challenge as an institution is to make the story of this man topical to the next generation of Americans. ... If we try to control the story, or direct it to an outcome, it will hurt us."

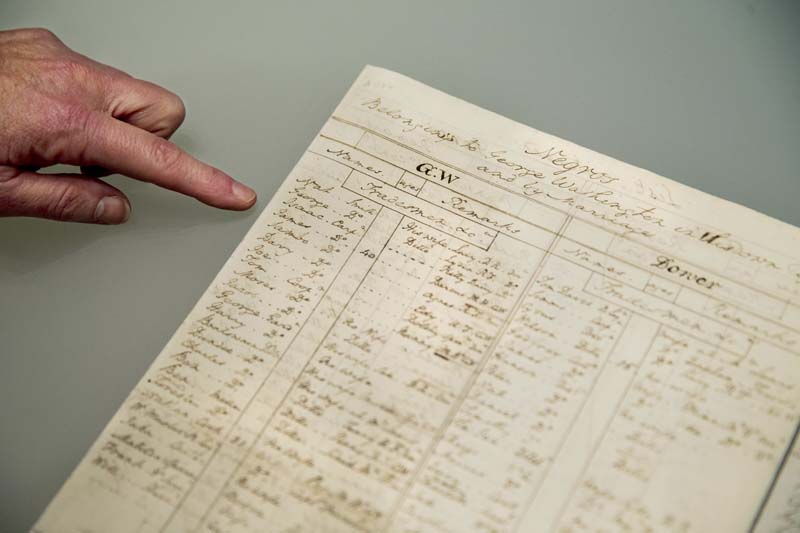

A centrepiece of the new exhibit, which will launch in October, is a display of Washington's handwritten list of slaves on the estate from 1799, likely written in preparation for his will. Washington freed his slaves in his will, upon the death of his wife, Martha. She ended up freeing the slaves before she died. Other slaves belonged to Martha Washington's family, and neither George nor Martha had any legal right to emancipate them.

The list, in Washington's bold, instantly recognisable handwriting, is a powerful connection to the man himself and the men and women who were registered as his property. The list also includes some commentary on the slaves. Washington describes 28-year-old Tom as "a good mower and an excellent ploughman but unfortunately from some tumour in his head, it is feared that blindness, partial if not entire, will ensue."

Throughout the exhibit, Mount Vernon endeavors to tell the story of 19 slaves who lived on the estate. Washington's meticulous record-keeping helped in some of the reconstruction, but curator Susan Schoelwer acknowledged limitations: The slaves were largely illiterate, so any written records about them come from the whites who oversaw them.

"We try to explore their stories," Schoelwer said. "I would not presume to tell them."

Still, Mount Vernon is not totally reliant on whites' perspective to tell the story. Oral histories passed down by slaves' descendants fill some of the gaps.

For ZSun-nee Matema of Hagerstown, Maryland, the family history was whispered and talked around, but always present.

"My father's people told me that if everything were known about our family's history, it would topple the first family of Virginia," Matema recalled.

She didn't really know what to make of the cryptic comments. Matema always knew that she was a descendant of Caroline Branham, a slave who served as a house servant and was the person who found Washington ill in his bed the morning of his death in December 1799.

As she became more interested in her family's genealogy, she did her own research, which seemed to mesh with her family's oral history.

The scholarship is at the point where Mount Vernon, in the materials it is preparing for the exhibit, concludes that Caroline Branham's daughter Lucy was "likely fathered by George Washington Parke Custis."

That means Matema, in addition to being a descendant of Branham, is also a direct descendant of Martha Washington, since Parke Custis was also the grandson of Martha in addition to being the adopted son of George Washington.

Matema, for her part, said she credits Mount Vernon for its effort to tell the story of Mount Vernon's slaves as fully as it can, in the face of the limitations of researching an era when people were considered property.

"There will probably never be a full story told of the enslaved community," she said.