Capital spending low as only 7pc civil servants perform duties well

Kathmandu, May 25

Around two years ago, a motorbike carrying three went out of control and plunged off a narrow, hilly roadway at Bhorle, in Dolakha district.

Of the three, one landed on the banks of Tamakoshi River and died on the spot, while the other two, who were stuck in the middle of the steep slope, survived the accident.

The loss of life was tragic. But what followed was surprising.

“The two who survived the accident and other villagers, who had gathered at the spot, started blaming Upper Tamakoshi Hydropower Ltd (UTHL) for the mishap and demanded compensation,” said UTHL Spokesperson Ganesh Neupane.

Their logic, according to Neupane, was that the road on which the three were travelling was built by UTHL as an access way to reach the 456-megawatt hydroelectric project site. “The locals argued that if the road hadn’t been built by UTHL the accident wouldn’t have taken place, hence the demand for compensation.”

Although UTHL ultimately did not have to pay the money, heated debate that ensued did make the environment tense for a while.

“This is what happens when locals don’t take the ownership of projects being built in their locality. If there is no sense of belongingness, development can’t take place,” Baikuntha Aryal, head of the International Economic Cooperation Coordination Division at the Ministry of Finance (MoF), told The Himalayan Times.

Locals living in the vicinity of project sites, like Upper Tamakoshi, are usually told about downsides of projects, including problems related to household relocation and drying up of income sources. They rarely get complete information on how electricity generated by hydro projects reduces power-cut hours, aids industrialisation and stimulates economic growth.

These benefits, if properly distributed, will contribute to welfare of the people, and improve living standards of everyone in the country, including locals where projects are being built.

But since the wider advantages of projects are not clearly explained, locals easily get influenced by the resistive lot or vested interests of political parties and start placing unnecessary demands.

These are the reasons that have delayed construction of 132 kV Thankot-Chapagaon-Bhaktapur and 220 kV Khimti-Dhalkebar transmission line projects, and conversion of single-circuit Hetauda-Kulekhani-II-Siuchatar transmission line into a double-circuit transmission line.

“Once project implementation gets hit by these factors, the government cannot fully utilise money allocated for capital spending,” said Aryal, who previously served as the head of the Budget and Programme Division at the MoF.

“So, inability of locals to take ownership of projects has direct relationship with low capital spending.”

One of the daunting challenges faced by the government over the years is weak capital spending.

The problem here begins from the time budget is allocated for capital expenditure, which is low.

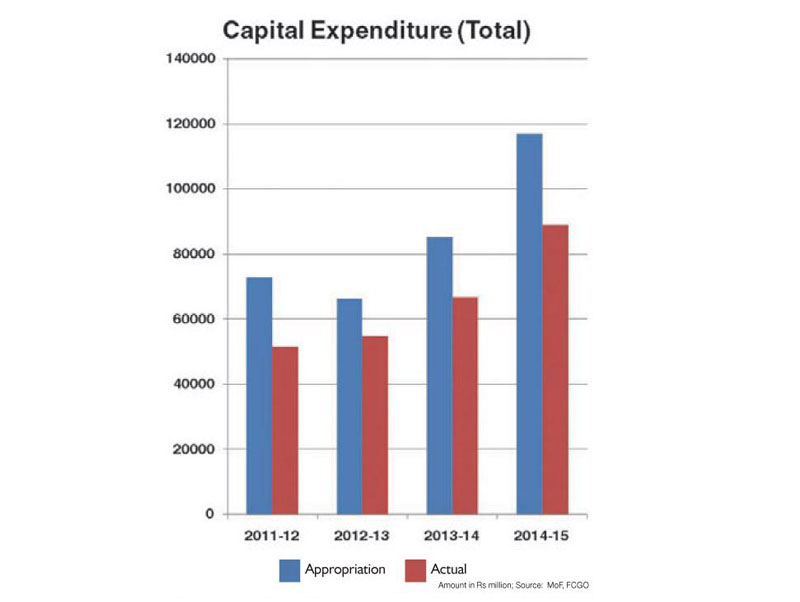

In the last four fiscal years through 2014-15, the government earmarked a maximum of 5.51 per cent of the gross domestic product for capital spending, with minimum allocation standing at 3.90 per cent of the GDP, show the data of the MoF and the Financial Comptroller General Office (FCGO).

Worse, even these paltry amounts were not fully utilised.

In those four years, the government, on average, was able to utilise only around 77 per cent of the funds allocated for capital spending.

As per the government’s classification, capital spending includes investment in land, building, furniture and fittings, vehicles, plants and machinery, civil works, and capital research and consultancy.

Surprisingly, the government — except in the year 2011-12 — had always overspent on vehicles, with investment exceeding over three times the allocated amount in 2013-14. But investment in other crucial areas remained low.

For instance, spending on civil works, which accounts for around 64 to 70 per cent of the capital budget, did not exceed 84.33 per cent of the total allocation in the four-year period between 2011-12 and 2014-15. It even fell to as low 71.54 per cent of the total allocation in 2011-12.

This is the same with purchase or construction of buildings, which accounts for around 12 per cent of the capital budget. Spending in this sector reached a high of 94.61 per cent of the earmarked budget in 2012-13 and fell to a low of 64.02 per cent of allocation in 2014-15.

Higher capital spending in areas, like civil works, is crucial because it helps to build critical physical infrastructure, like hydro projects, transmission lines and roads, which plays a supporting role in unlocking private investment. This is the reason why higher capital investment is considered as the bedrock for sustainable economic growth.

“But in Nepal, the problem begins from the time plans are charted out to build a project,” said Aryal.

It is known that most of the project plans here are made in a hurry without conducting much research and study.

“The fact that projects selected in a haphazard manner cannot be implemented dawns on line ministries only after they are incorporated in the fiscal policy,” according to Aryal. “They then start demanding for budget reallocation from as early as second month of the new financial year.”

But even if the projects are feasible for implementation, many line ministries do not extend full spending authority to bodies that implement the projects.

The MoF generally gives full spending authority to line ministries on the first day of every fiscal. Based on this, line ministries have to grant permission to project implementers to spend money allocated for projects.

But delay in extension of this permission has always compelled project implementers to make rounds of concerned ministry every now and then, which not only waste their time but create resource crunch for projects that could be completed on time.

“Public Expenditure Tracking System that we had developed earlier had found this as one of the factors that constrained capital spending,” Aryal said.

These types of bureaucratic bottlenecks and red tape are not new to Nepal. And they always hit implementation of public projects. But this should change as low public capital spending puts private investment at bay.

A report prepared by the National Planning Commission says every rupee that the government contributes to gross fixed capital formation draws investment worth Rs 4.40 from the private sector.

It is not that government officials who have assumed responsible positions are completely unaware of this fact.

Yet, they don’t act.

“This is due to flawed incentive structure in bureaucracy,” said Aryal. “Here, treatment towards performers and non-performers is almost the same. So, officials choose not to do anything rather than do something good and get into hassles.”

No wonder, only seven per cent of civil servants are said to be performing their duties well, while others are considered as free riders here, Aryal said, quoting a report, a copy of which could not be obtained by THT.