Accessibility for inclusion: For those living with disabilities

The universal design concept asserts that anything and everything should be designed in order to be accessible not only to people with diverse disabilities, but more generally to the broadest possible spectrum of humanity

Each year, on December 3, the world marks International Day of People with Disabilities (IDPD) It is a day on which we promote public awareness about the challenges faced by people with disabilities, and the role communities and societies can play in eradicating the barriers to social inclusion. The theme for this year’s IDPD is “Promoting the participation of persons with disabilities and their leadership: taking action on the 2030 Development Agenda” while the national theme is “The Future is Accessible”, which means we all look towards a future without barriers.

More than one billion people live with some form of disability worldwide. In the years ahead, disability will be an even greater concern due to ageing population and the higher risk of disability in older people as well as the global increase in chronic health conditions, such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer and mental health disorders. Understandably, people with disabilities have poorer health outcomes, lower education feats, less economic contribution and higher rates of poverty than people without them.

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) came into force in 2008 and strengthened the understanding of disability as a human rights and development priority.

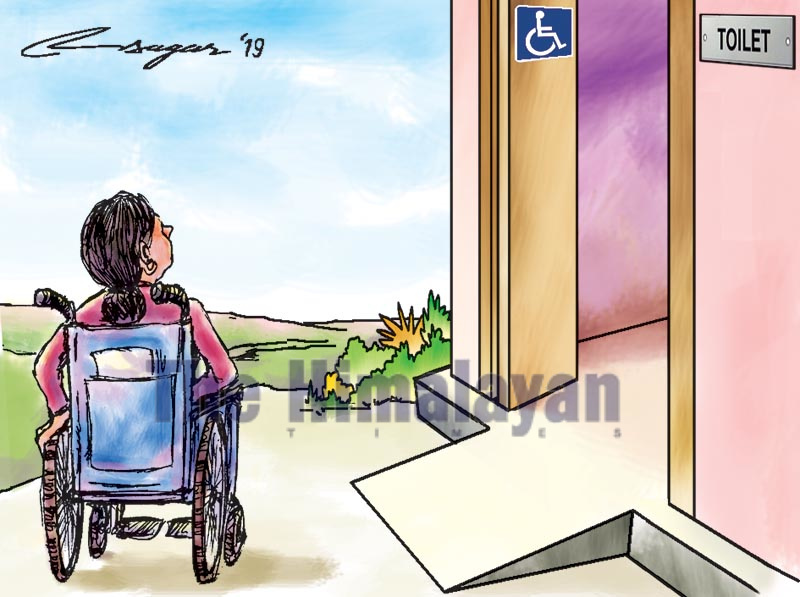

A person’s environment has a huge impact on the magnitude of disability. Inaccessible environments create disability by creating hurdles to participation and inclusion. Examples of the possible negative impact of the environment are a deaf person without a sign language interpreter, a wheelchair user in a building without an accessible toilet and a blind person using a computer lacking screen-reading software. The environment could be changed to improve health conditions, prevent impairments, and improve outcomes for people with disabilities. Such changes can be fetched by legisla¬tion, policy changes, capacity building, or tech¬nological developments.

Article 9 of the UNCRPD cherishes “accessibility” as one of the treaty’s eight general principles. In the preamble of the Convention, we learn that accessibility is closely tied to the evolving definition of disability. The universal design concept asserts that anything and everything should be designed in order to be accessible not only to people with diverse disabilities, but more generally to the broadest possible spectrum of humanity. For example, public buildings designed with ramps at entranceways allow for the easy movement of persons with mobility disabilities, along with pregnant women; parents with a baby carriage; people with injuries; and older persons. In the same way, for information accessibility, television programmes with subtitles and voice over ensure accessibility to people with hearing impairment as well as those watching in a noisy setting.

The Sustainable Development Goals have a strong and explicit focus on disability, promulgating a socially just and human rights-based approach where development efforts include all people, even those at the very margin of the society. The 2030 Agenda and the SDGs are both evidently inclusive of people with disabilities. They can be used as an advocacy tool to draw the attention of decision-makers for the creation of disability-inclusive policies and programmes.

Following Nepal’s ratification of the CRPD in 2010, the country has made notable progress in the disability sector. In 2015, Nepal adopted a democratic and an inclusive constitution, which assured a comprehensive set of rights for people with disabilities, with special provisions to ensure their access to health care, education, social justice and proportionate representation in the local bodies.

The Disability Rights Act 2017, which swapped the Disabled Persons Welfare Act 1982, made a vital departure from the welfare-based approach to the rights-based approach to disability. The Act acknowledges the principles on which the CRPD was established, and amplifies the definition of persons with disabilities in line with the Convention, eliminating and banning offensive narratives.

Why is there a need for disability awareness? Simply, disability is not mainstreamed and is often overlooked. Only a few people with disabilities know their rights, and deeply rooted stereotypes towards people with disabilities still exist. Civil servants must make policies to ensure there is more than just nominal representation of people with disabilities in politics.

Within the legal and policy frameworks, governments should engage the civil society and private entities in implementing initiatives to tackle inequalities of accessibility. Engaging people with disabilities throughout all stages of design, development and deployment safeguards access to products and services. This, in turn, can reduce costs and serve wider markets.

The CRPD calls on States Parties to take measures on accessibility not only for government-owned facilities and services, but also in the private sector. In the federal structure, the measures should be designed in consultation with people with disabilities, disabled people’s organisations and their networks, such as the National Federation of the Disabled, Nepal. This will help to break the brutal barriers and open up better opportunities for disability-inclusive development.

Gairapipli is senior communications officer at Humanity & Inclusion